Column: When homeless people tell their own stories, we should listen and not turn away

- Share via

There’s a podcast I find myself listening to lately that isn’t produced in a studio. It hasn’t been polished and smoothed like a rock tossed in a tumbler. It contains stumbles and sometimes unexpected clattering.

But at its best, in its intimate stories from the streets and its insights from the experience of living on them, it cuts right through the background noise about homelessness.

Theo Henderson, 46, calls a park in Chinatown home and records “We the Unhoused” on his cellphone every week — no small feat as he also tries to survive on our streets. His parents, his only real safety net, died when he was a young man. And even though he graduated from college and used to teach elementary school, in a series of calamities starting with a diabetic coma during the recession, he lost his job and his housing and his economic stability. He now sleeps outdoors, on concrete.

In recent months, he has been chronicling the travails of others who for a host of reasons once lived under roofs but now don’t. He is one of a number of people I know of who are homeless in our city who also document homelessness. They’re in that world. They know it in ways I do not. When I come across them, I pay attention.

This week, our governor, Gavin Newsom, devoted his State of the State address to California’s crisis of homelessness. He called it “a disgrace” that we ignored for too long. “We turned away when it wasn’t our sister, our brother, our neighbor or our friend,” he said, or when it was and no help was forthcoming.

Now there’s no turning away. It’s everywhere you look. And I think we have to look, closely and steadily.

Massive fixes are required — so much more housing, so many more support services. The vast majority of that work will fall to our government, at all levels.

But as individuals, I feel it behooves us to educate ourselves in order to understand the many layers of the problem. To figure out what useful actions we can take — whether alone or in groups, through donations or directly — when no official aid is at hand. To determine what we should be demanding our elected officials do to produce the kind of help those in need say might actually work for them.

I’ve talked in the past about the benefits for all concerned of reaching out to people on the streets, asking them what immediate help they need, trying to provide it, listening to them talk about their lives. I know not everyone will feel comfortable doing this. But there are other ways to go to the source.

“We the Unhoused” can get angry — at overzealous police and business improvement districts, at City Council members. Henderson takes jabs at my colleague Steve Lopez, too, which I’ve told him I think is unfair.

He has had the word “homeless” spat at him too often, he says, to want to use it himself. On his podcast, which he is trying to raise money to keep going, he simultaneously offers advice to the unhoused and to the rest of us who might be far too quick to write them off.

In one episode, he focused on violence against people who are homeless. He talked to Freddie, whose wife had died and who had then been evicted from the apartment building they’d managed; Freddie was living with his two cats near his former home when someone threw an incendiary device at his tent. He spoke to others who described having ice cubes thrown at them in the middle of the night, who worried that strangers might hand them poisoned food or that they could be attacked at any moment by people who want them gone.

He reminded the rest of us, as he often does, of the fragility of life — that we could find ourselves suddenly unhoused, too, and that we should respond accordingly to our neighbors who already are.

He asked that we think twice about doing such things as calling police to request that encampments be removed and spoke about the unintended consequences of cleanups that set people who are homeless even further back when they lose crucial IDs and supplies.

He asked us to ask ourselves, “What part do I play in perpetuating the hateful rhetoric or the uplifting rhetoric and the uplifting actions to help unhoused people find their best selves?”

Do we play a role? Is it a role we can be proud of? These can be uncomfortable questions.

There’s a very creative guy I sometimes run into around town by the name of Bumdog Torres. He is homeless, he says, more or less by choice. If someone gave him an apartment, he’d move right in, he told me — but he doesn’t want to make his life all about working to afford one. Torres, who grew up poor in Crenshaw and quit school after seventh grade, has chosen to live his life as a wandering storyteller. He’s made two feature-length films while living on sidewalks. He brings in money by selling the DVDS ($25), along with T-shirts of his image in silhouette ($50) and copies of photographs he takes as he pushes his cart around the city ($10).

Torres, 50, is a voracious reader who has taught himself many things. When a nearby coffee shop switched ownership and tossed out a beat-up, scratched-up mirror in a gilded frame, he began a series of striking self-portraits inspired, he told me, by Vivian Maier, the Chicago nanny whose extraordinary images were discovered only after her death.

Torres’ face often appears in the gilded mirror, which he places in the scenes he shoots of people living in dire straits on the streets. Sometimes I imagine that if my own face were reflected in those photos, they would serve as a not-so-subtle critique of my miniscule efforts to reach out to those around me in need. I hand out socks and blankets and TAP cards and gift cards. I bring people what they tell me they could use. I try to make connections and show that I care. But I know it’s so little in the face of such great need.

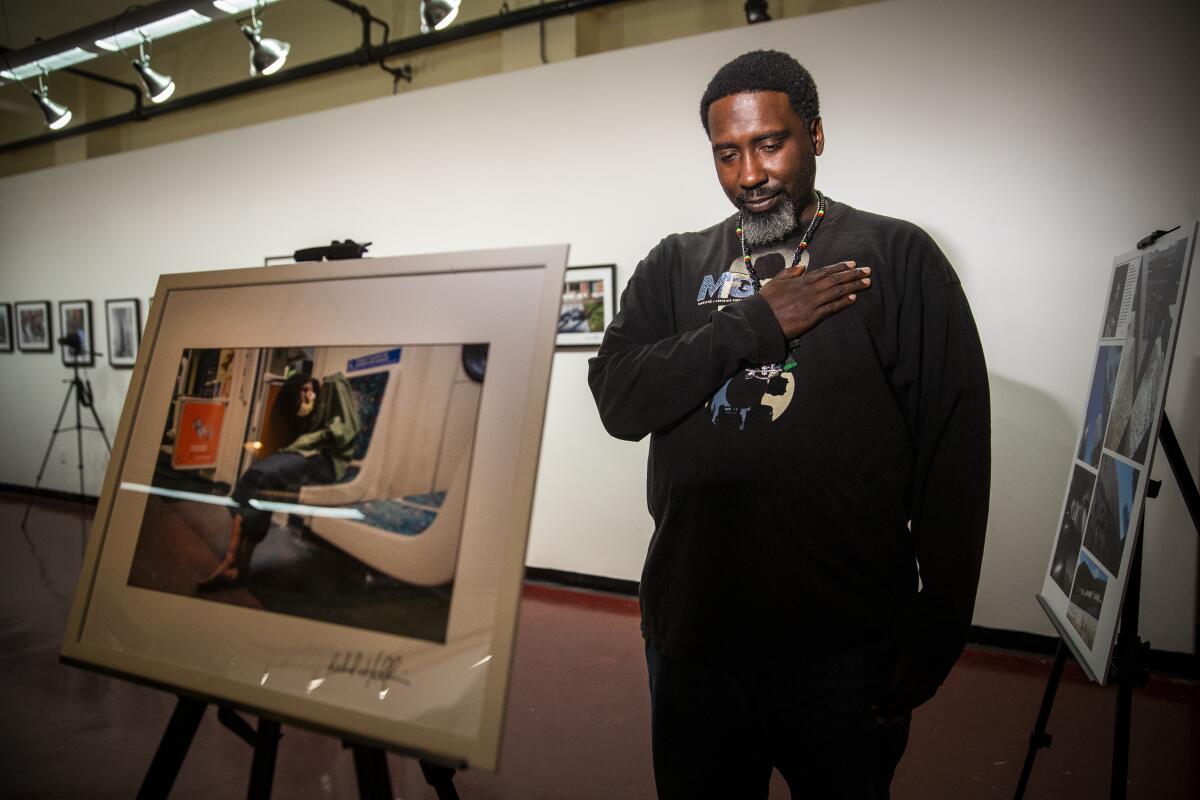

Lelund Nathaniel Hollins’ photographs make me feel that need powerfully. They cry out the lack of comfort, the loneliness, the isolation. Hollins, who does not have a home and often sleeps on public transportation, photographs others who do the same and who stretch out on our sidewalks and bus benches.

He’s part of an ongoing workshop in the journalism department at Cal State Northridge, in which seniors studying photojournalism coach those who are homeless or have been homeless, teaching them street photography skills so they can tell their own stories. CSUN journalism professor David Blumenkrantz started the workshop, which is called “How We See It.” It’s turned out to be an even greater learning experience for the CSUN students, they told me, than it has for their protégés. I met a lot of the group last month when the work was exhibited at the Museum of Social Justice in the heart of El Pueblo downtown. They had all bonded and become close friends.

“Being able to recognize my privilege as someone who is housed and someone who has food every day and someone who has a family, it opens your eyes to the world,” one of the CSUN crew, Shae Hammond, told those gathered in a short speech.

I met Tim Caffery, who at the time was living in Griffith Park. (He’s since been rousted by rangers and is tucked in along a freeway.) Bobby Buck, who used to be on skid row, told me he liked taking pictures of people who are homeless, as he used to be, as a way to bring them dignity and light in the darkness.

Hollins, 45, said the photos he takes hurt even his own heart. He talked about the ones of the people hunched over in their seats on the Metro, their scant worldly belongings encircling them. (He rents a storage space and so can own more.)

“The harshest is when you see somebody make that seat into their only home,” he told me. And I had to agree.

Which made me think about one thing I particularly like about the podcast, “We the Unhoused”: the way Henderson closes nearly every episode.

“Thank you for listening,” he says. “And may we all again meet in the light of understanding.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.