The simple art of hard-boiling eggs, with a heaping side of geekery

- Share via

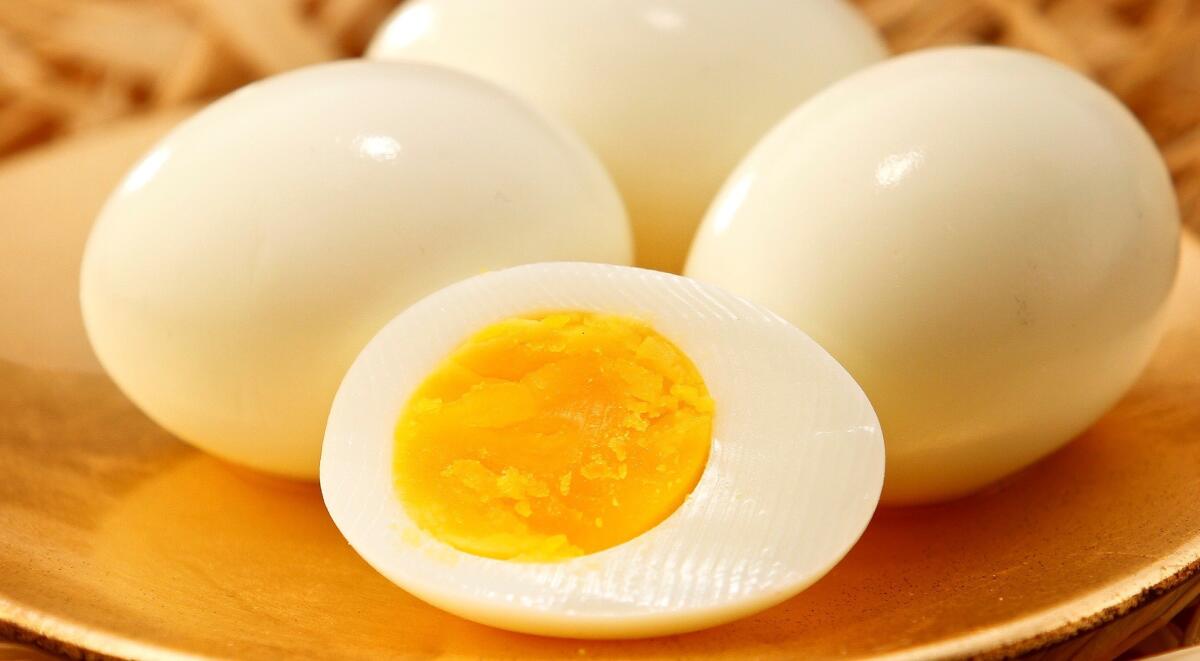

How do you cook a perfect hard-boiled egg? It’s really quite simple, thanks to a neat little bit of kitchen physics.

- Arrange the eggs in a single layer in the bottom of a pan and cover completely with room-temperature water.

- Set on high heat, and when the water just begins to boil, cook for 1 minute.

- Turn off the heat and let the eggs stand in the pot for 12 minutes.

- If you’re going to use them right away, drain the eggs, shake them in the pan to crack the shells and plunge them into an ice-water bath to cool for a few minutes. If you’re going to store them, plunge them into the ice-water bath uncracked and let them sit for an hour or so.

The trick is that because the eggs are cooking off the heat, the water in the pan is cooling while the egg proteins are still heating. Because the yolks aren’t set until they reach about 160 degrees, and because the water cools fairly rapidly to about that temperature, you’ll never get that dreaded green ring, no matter how long you leave them.

We have noticed a slight toughening of the white if you leave them for a longer time – that’s because the whites are much lower in fat and so finish cooking at a lower temperature. Still, it’s not really enough to worry about unless you’re especially picky (which we, of course, are).

Remember that it’s very important to use older eggs rather than fresher when hard-boiling, because they’ll be easier to peel. Aging affects the chemical balance of the egg, making it less likely to adhere to the shell. Also, as eggs age, the air pocket within them expands, making peeling easier.

And if you’ve ever had eggs explode while they were cooking, that air pocket is the culprit. When you drop eggs into rapidly boiling water, the air expands quickly as it heats – so quickly it can crack the shell and leak egg out into the cooking water.

If you start the eggs in cool water and warm them gently, the air pocket expands slowly enough that it can leach out through the porous shell (watch carefully and you’ll see a chain of tiny bubbles coming from the end where the air pocket is).

And that pesky green ring? It’s the result of serious overcooking – at high enough temperatures, the white gives off hydrogen sulfide gas as it cooks, and that reacts with traces of iron in the yolk to form iron sulfide.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.