New life for Gregory Ain house in Silver Lake

- Share via

Tony Unruh and Keith Sidley had much in common. Both were Jewish architects from South Africa transplanted to the same Los Angeles neighborhood. Both had married non-Jewish women from Maryland, and both had two young kids. Perhaps most important, both had an affinity for Midcentury architect Gregory Ain.

Unruh had bought Ain’s old architecture office on Hyperion Avenue. Sidley was living with his family in a Silver Lake home designed and built in the early ’40s by Ain.

As their friendship grew, the architects spent many nights talking about how they could renovate Sidley’s house. He and his wife, Kathleen Nolen, had fallen in love with the house at first sight and bought it in 1987. Despite its ’60s shag rugs and other dated décor, it had many Ain touches: the sleek Modernist lines, a three-tiered design with a drive-through garage that eliminated the need to turn around on a narrow street, lots of wood cabinetry, and clerestory windows that provided light and vistas while keeping neighboring homes out of sight.

For Sidley, the cost of restoring the house was a worry. For Unruh, the thought of taking on one of his idols was daunting. So for a long time, the restoration was just talk.

Then Sidley became ill with a brain tumor. In 2008, he died.

At this point, the house was nearly 70 years old and falling apart. Nolen was dealing not only with Sidley’s death but also with aging parents back East. With the pall cast by Sidley’s death, the house was a sad place.

“I loved the house and wanted it to live forever,” said Nolen, who by 2012 knew the time had come to face reality. “It was such a masterpiece, it would be wrong to let it get torn down, or fall down.”

PHOTO GALLERY: Gregory Ain house in Silver Lake

She approached Unruh about making repairs. He jumped at the chance, knowing it would be a labor of love and a financial challenge, but also an opportunity to bring to fruition all that he and Sidley had talked about over the years.

“It was Tony’s destiny to do this house,” Nolen said, adding that everything he talked about, such as pushing the hillside from the back of the house and opening up the tiny kitchen, was something she had dreamed of doing. It was hard for her to start, to think about changing the house she loved so much.

“Tony said something that struck a chord: that the kitchen was built for a different era, for someone working in the house, not living in it,” Nolen said. “That freed me.”

The house was a reflection of the sociology of its period, said Unruh, who worked on the project with his partner, Trish Boyer, who oversaw the interior design. Their approach: Look at the house and ask what Gregory Ain would do if he were rebuilding it today.

As a young architecture student driving the streets of L.A. on his way to the Southern California Institute of Architecture in the late ’70s, Unruh noticed a building on Dunsmuir Street that intrigued him. He would come to find out that it was designed by Ain.

“No one knew who he was,” Unruh said, but the building spoke to him. He wanted to buy it, but as a struggling student, he could not get the money together. About 10 years later, Ain’s architecture office in Silver Lake came on the market, and Unruh’s purchase cemented his connection with Ain’s work.

“I feel like I’m living inside Gregory Ain’s brain,” he says.

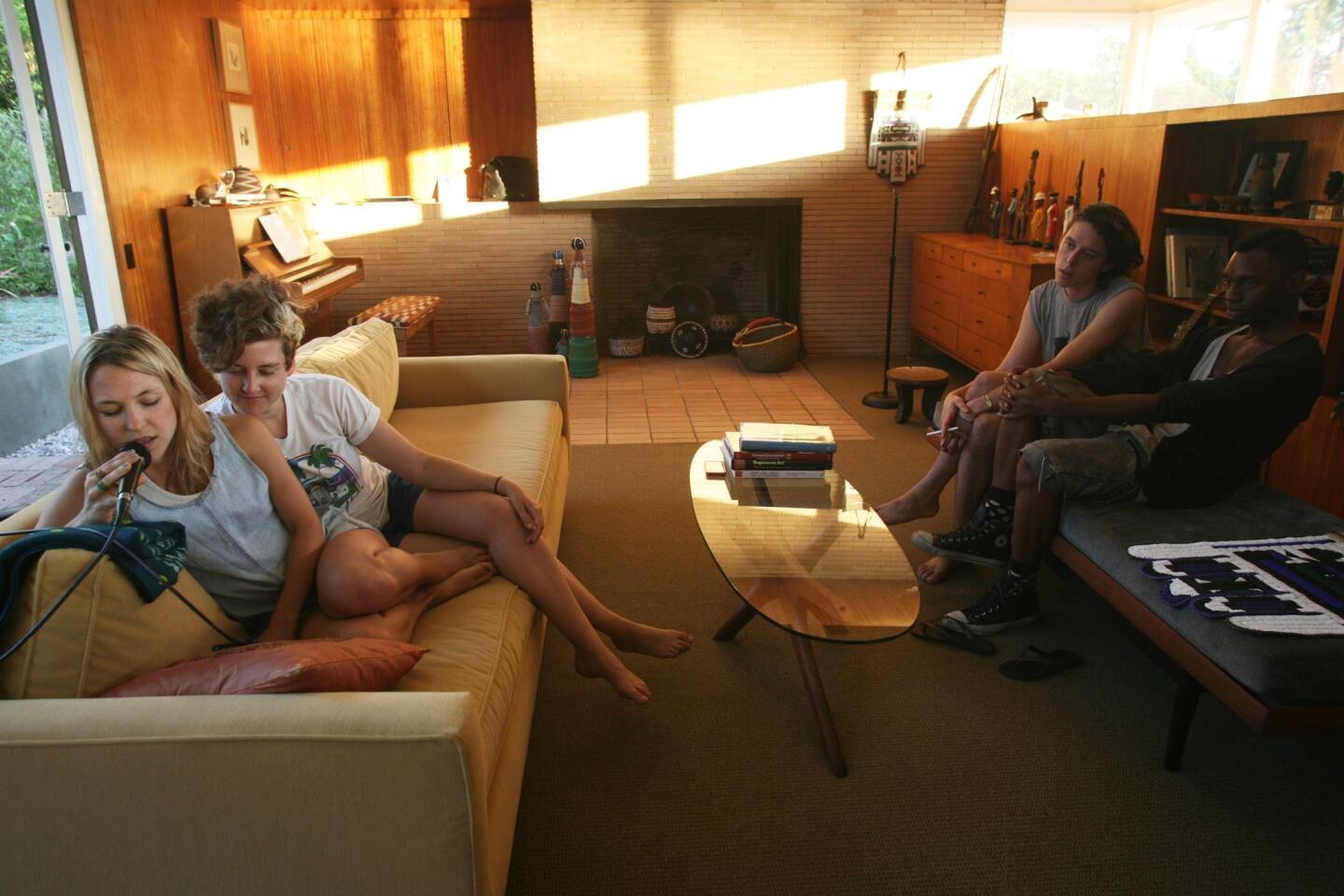

At Nolen’s house, rooflines were extended. Ceilings were raised. In the living room, strip lighting was recessed into the pitched ceiling, whose fabric covering was replaced with a coat of white paint. Mahogany cabinetry was painstakingly repaired, like fitting pieces into a jigsaw puzzle. The veneer of some cabinets was replaced with white Formica for two reasons: The mahogany could be used to repair cabinetry damage elsewhere, like a skin graft, and the white Formica would serve as a reflector, bouncing natural light from the clerestory windows into the room.

In the hallway leading to the bedrooms, the dark wood paneling was whitewashed and dark floor tiles were replaced with lighter Fritz tiles, whose stone chips reflect light. The bathroom, whose maroon tiles were cracked, also was brightened with white tile and larger windows. Shelves and walls are now filled with Nolen’s African textiles and pottery, things she has lovingly collected for decades.

“I see these things and remember every story, every conversation we had with the boy who was selling it or the man who was making it,” Nolen said.

Nolen’s daughter Samantha summed up the changes this way: “There was a lot of sadness in this house,” she said. “Now, it’s the most amazing house. It’s a happy house now.”

Clarification: This article was updated at 3 p.m. Aug. 2 to clarify who managed the interior design.

ALSO:

Gregory Ain remodel in Tarzana

Party time at a Gregory Ain house in Mar Vista

JOIN US:

@latimeshome | pinterest.com/latimeshome | facebook.com/latimeshome | facebook.com/latimesgarden