As El Niño gathers strength, lawmakers look to fortify Pajaro’s flood-ravaged levee

- Share via

As Californians brace for the possibility of yet another wet winter — thanks to a looming El Niño — anxiety is growing in the Central Coast towns of Pajaro and Watsonville, where epic storms caused extensive flood damage earlier this year.

On Tuesday, California Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas (D-Hollister) introduced legislation designed to expedite construction and upgrades along the Pajaro River levee — a 74-year-old earthen flood control berm that breached just before spring, inundating the mostly migrant farmworker town of Pajaro.

“The historic storms and flooding this past March were devastating to the Pajaro community,” Rivas said in a prepared statement. “These levees need to be upgraded now, urgently, and this allows us to perform critical work on a much faster timeline.”

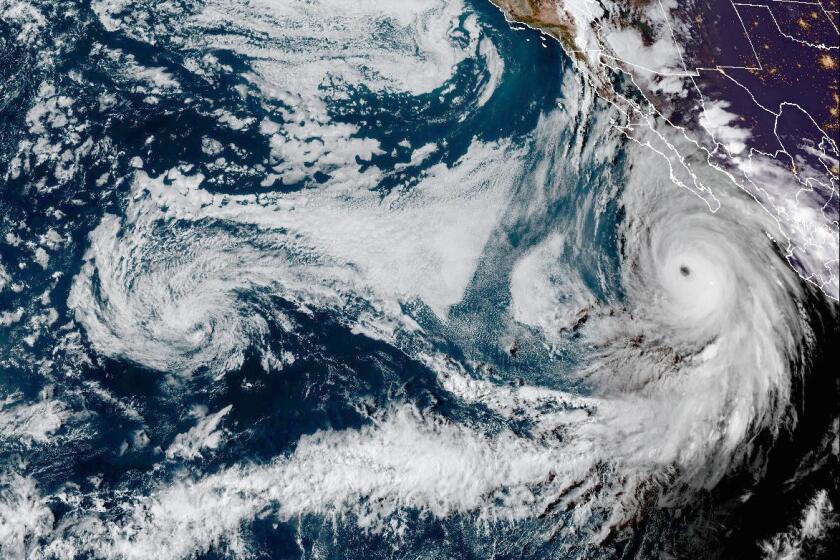

Off the California coast sits a marine heat wave that has persisted since 2014. Scientists aren’t sure whether it’s now permanent, or a decades-long blip on the map.

Although Rivas declined to be interviewed by The Times, a flooding expert said the legislation was badly needed.

“I think this (legislation) is really important because of the strong El Niño in the Pacific and the marine heatwaves in the North Pacific, which could result in increased precipitation rates and flooding,” said Deirdre Des Jardins, Director of California Water Research, an organization dedicated to analyzing the state’s water infrastructure.

She said the long-range seasonal forecasts suggest a strong El Niño, so state and local agencies should be managing for “chaos.”

“The prudent thing to do is to prepare for the possibility of another winter like 1982-83 and 1997-98,” said Des Jardins, referring to former El Niño years when the state was hit with historic flooding.

The bill, AB 876, would exempt the levee project from various state and local environmental laws and regulations that could slow construction by years.

Upgrades are slated to begin next year. However, lawmakers say that without this legislation, jumping through the bureaucratic hoops of state approvals could delay construction until 2025 and take years to complete.

“The best estimate is that this bill would shave a year off the beginning of the main project and maybe more over the life of the project,” said Zach Friend, a Santa Cruz County Supervisor and Pajaro Regional Flood Management Agency Board member.

Plastics are everywhere. As an environment reporter, I make informed choices when shopping, trying to minimize the amount I bring in. Or I thought I was.

An executive order signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom earlier this month will speed up repairs and maintenance on the levee.

However, it is both temporary and “really for the repairs and maintenance this winter,” said Friend. Rivas’ bill, on the other hand, “covers construction.”

“This legislation removes one of the remaining hurdles toward making this project a reality,” said Friend. “Speaker Rivas’ actions will help expedite the reconstruction and remove any regulatory barriers as we move forward ensuring the protections the Pajaro Valley has long deserved.”

For years, little was done to improve the structure, even though federal, state and local governments knew the levee was at risk of breaching.

After the levee breached, an official with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — which built the levee in 1949 — told the Times that rebuilding the levee never penciled out, in terms of “benefit-cost ratios.”

“It’s a low-income area. It’s largely farmworkers that live in the town of Pajaro,” Stu Townsley, director of the Army Corps’ San Francisco district, said at the time. “Therefore, you get basically Bay Area construction costs but the value of property isn’t all that high.”

But in 2021, with the passage of the federal Infrastructure Jobs Act and a shift in the way the Army Corps assessed new projects — incorporating social welfare and equity as criteria — state and federal funds were secured and planning began for levee construction.

Unfortunately, the lengthy time frame required for major infrastructure projects such as levee construction — which require planning, contract bidding, and oversight from state and federal environmental authorities — meant that when a series of atmospheric storms hit the Central Coast this year, the aging and neglected levee couldn’t hold back the roaring waters. Watsonville, with sits on the other side of the river, escaped widespread flood damage.

Now, as an El Niño weather pattern takes hold in the Pacific, residents and lawmakers worry another breach is likely if construction doesn’t start soon.