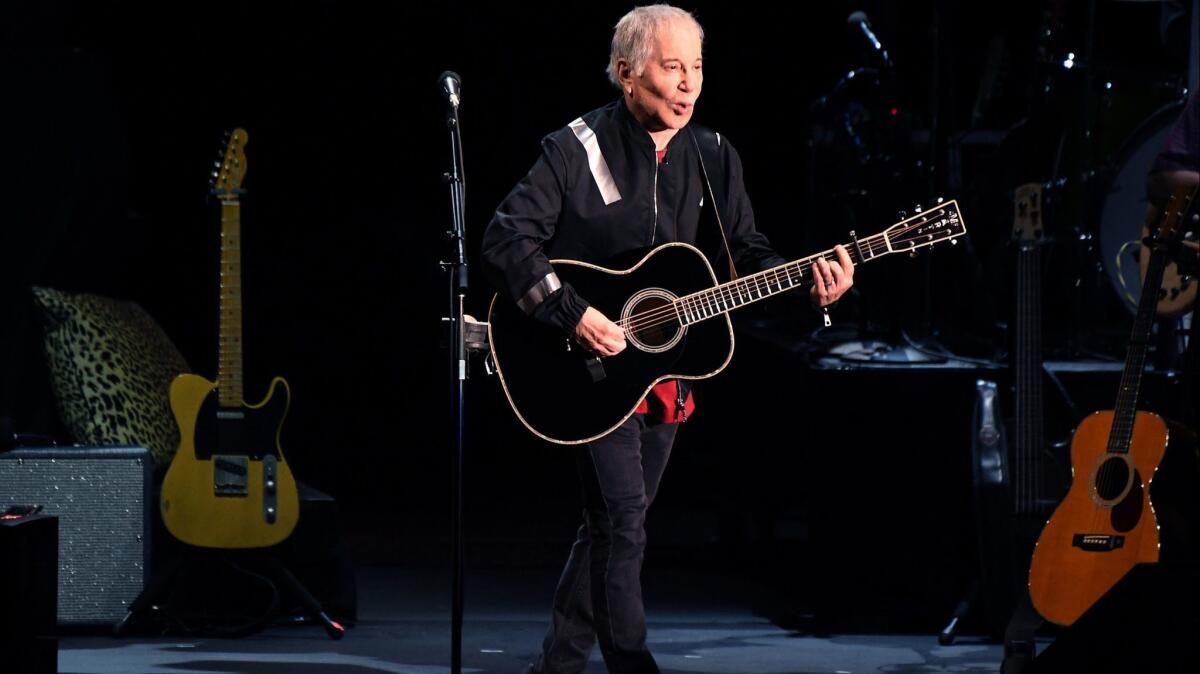

Paul Simon, in the homestretch of a farewell tour, talks of unique journey through his past for ‘In the Blue Light’ album

- Share via

Reporting from New York City — A strikingly detailed self-portrait of painter and photo-realist Chuck Close hangs prominently on one wall of Paul Simon’s elegant office in a high-rise overlooking Central Park.

From a distance, a viewer can perceive Close’s piercing blue eyes, his black, horn-rimmed round spectacles and precisely trimmed mustache and goatee. Yet on closer inspection, from just inches away, the subject’s features dissolve into a richly colored mosaic of discrete geometrical shapes and images that form the whole — the same way any song can be broken down into myriad phrases, words, letters, chords and notes.

For the record:

8:35 a.m. Sept. 11, 2018An earlier version of this post identified “How the Heart Approaches What it Years” as a song from Simon’s “Hearts and Bones” album. It was originally released on his “One-Trick Pony” album.

“My friend Chuck Close over there,” the 76-year-old singer and songwriter said last week, gesturing toward the artwork. “That used to be one of our big conversations: the similarities between painting and songwriting.”

Simon sat in a chair across the spacious room from the image, glancing up to admire its craft. The office itself reflects the intersection of music and visual art that intrigues the veteran singer-songwriter: an exquisite baby grand piano, a weathered upright bass and, on another wall, a neo-primitivist art piece made from more than a dozen well-used violin bows strung together with raw fabric backing.

Next to the doorway is a glass display case housing many of the 16 Grammy Award statuettes he’s collected for his music over the past 50 years.

Simon takes the analogy of music as painting to a new level with “In the Blue Light,” a collection of 10 songs, out Friday, that span most of his 48-year solo career. He not onlyrevisits them with sometimes dramatically reconfigured musical arrangements, but also revises old lyrics in ways that are both painterly and surgically precise.

The project constitutes a rare instance of a pop musician engaging in a practice more common for visual artists, who sometimes return to a particular work time and again, adding a new color, shape or texture in the pursuit of some ever-evolving ideal. It’s the polar opposite of one fundamental aspect of recorded music, which freezes songs at a specific moment in time.

As potentially the final word on his recorded legacy, Simon overrules that precept on “In the Blue Light.”

In his new take on “One Man’s Ceiling Is Another Man’s Floor,” the cascading opening arpeggios become dreamier and the contrasting verses are bluesier than on the original recording for his 1973 album “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon.”

“How the Heart Approaches What It Yearns” and “Some Folks’ Lives Roll Easy” take him into the realm of free jazz thanks to a wide-open instrumental backing from New Orleans trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, pianist Sullivan Fortner, bassist John Patitucci and other jazz pros. The original poignancy of “The Teacher” is heightened with a sensual undercurrent of Spanish classical guitar accompaniment from Odair and Sergio Assad.

Many musicians, of course, rearrange songs from time to time to bring a fresh perspective to live performance. Bob Dylan is the quintessential mighty rearranger, and Simon also mixes songs up considerably for his Homeward Bound farewell tour.

It’s coming into the home stretch this month with final performances at Madison Square Garden on Sept. 20 and 21. His swan-song show is set for Sept. 22 in Flushing, Queens, where he grew up seven decades ago after his family moved there from Newark, N.J., when the future Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee was just 3.

“It’s a life choice,” he said of retiring, “not a career choice. And it seems like a good life choice. In the end, I’d rather say ‘I had a great life’ than end up saying, ‘Well, I had a great career.’”

The tour dovetails with the album and its innovative new arrangements, two of which he’s sharing with concert-goers: “Can’t Run But” from his 1990 album “The Rhythm of the Saints,” and “Rene and Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After the War,” from his 1983 effort “Hearts and Bones.”

Both feature New York’s adventurous yMusic instrumental sextet in what is one of the highlight segments of what he’s still insisting is his final go-round on the concert trail.

I’d rather see India.

— Paul Simon on retiring from touring

“Can’t Run But” originally had a verse referencing what he observed happening in the music business almost three decades ago: “Down by the river bank / A blues band arrives / The music suffers, baby / The music business thrives.” Now, however, the forces at play are a bit different. Instead of a blues band, it’s a DJ who arrives at that river bank: “The sub-bass feels like an earthquake /The top-end cuts like knives.”

The musical accompaniment remains rooted in the kinetic South American rhythms on the original recording, but they take on the insistent energy of Philip Glass/Steve Reich minimalism in composer-guitarist Bryce Dessner’s rearrangement for yMusic.

“The arrangement is killer,” Simon said, “maybe better than the song. It benefits from the original arrangement by [Brazilian instrumental group] Uakti. ... In a sense, that’s the best of what world music is: When people take a piece of information from one culture and enrich it with another culture.

“The original Uakti track is a great track, and this arrangement, especially with that section that lets yMusic really rip, that’s a big hit in the show. At that moment, when you hear the virtuosity of the players, you realize as an audience — maybe I’m just imagining this, but I think not — all of a sudden you see the scope of what’s going on, from rhythm and pop and folk to African to neo-classical and that all of this flows together and it all works, even though you might think it was disparate and not going to work.

“But it does work,” he said.

Simon speaks deliberately, periodically stopping to consider the precise word he’s after to express what he’s feeling, a practice that’s made him one of the most revered songwriters of the rock era. He also seems ever ready to engage in critical analysis of music — that of others and his own, another quality that informs “In the Blue Light” and the farewell tour.

A song like ‘El Condor Pasa.’ Artie [Garfunkel] and I never thought we couldn’t do that as a pop song, even though it’s a 300- or 400-year-old [Peruvian] song.

— Paul Simon

“I think I’ve thought like that ...” he said, taking a long pause before finishing the thought, “forever. Go back to a song like ‘El Condor Pasa.’ Artie [Garfunkel] and I never thought we couldn’t do that as a pop song, even though it’s a 300- or 400-year-old [Peruvian] song. Pop music has always been able to go to some odd places.”

A seasoned pop music polyglot, Simon cites the syncopated, reggae-ska influence underscoring the Paragons’ 1957 doo-wop single “Florence,” the stateside popularity in the ’50s of the South African instrumental “Skokian” and the unlikely 1963 chart success of Japanese singer Kyu Sakamoto’s “Sukiyaki.”

“The way I think about sound is how sound connects,” Simon said. “Having thought about it for a looong time, I sometimes find connections that you wouldn’t find unless you’d been thinking about it for a long time. I might think, ‘This music and this music both use the drone. So their commonality is the drone.’ So if I start with the drone, maybe I can mix things they play on top of the drone together. Or maybe I can’t. But at least I understand where the mixture might occur.

“That’s how you mix sound — you mix sound like mixing colors,” he said.

In other songs reimagined on the new album, sometimes it’s a single word that’s new. For “How the Heart Approaches What It Yearns,” another song from his 38-year-old “One-Trick Pony” album, he alters a scene originally set “In a phone booth / In some local bar and grill,” making it a notch more specific by changing it to “some downtown bar and grill.”

For Simon, it’s a way to take another shot at a few of the hundreds of songs he’s written, which he felt, either at the time or in retrospect, were “almost right” to begin with. Others he chose because they were personal favorites that got scant attention the first time around.

Among the latter is “Pigs, Sheep and Wolves,” a deep track from “You’re the One,” one of Simon’s lower-profile albums. It is reconceived as a New Orleans second-line street parade number, played by Marsalis and several of his Crescent City jazz cohorts.

A couple of years ago, Wynton said, ‘I really like that song ‘Pigs, Sheep and Wolves.’ I felt really good about him saying that.

— Paul Simon

“A couple of years ago, Wynton said, ‘I really like that song ‘Pigs, Sheep and Wolves,’” Simon said. “I felt really good about him saying that. It means he was listening to a whole record, because nobody paid attention to that song. I liked it a lot on the album, but nobody [else] liked it. Everybody thought it was a weird performance by me. I didn’t think so.”

He’s referring to his conversational, half-sung, half-spoken delivery of the lyric, veering as close as a then-almost-50-year old esteemed white singer-songwriter from Queens might get to rap. In reality, it probably hews closer to the Broadway tradition of non-singing actors such as Rex Harrison, Robert Preston and Richard Harris when they were cast in lead roles for musicals.

Marsalis and company take the whole “Pigs, Sheep and Wolves” number to the cradle of jazz and much of the R&B and rock that influenced Simon as a boy.

“It does feel right to take it to New Orleans,” Simon said. “It’s an urban song about racial profiling, and New Orleans certainly is one of the cities where that would apply. He knows that genre, he grew up with it.

“We overdubbed the tambourine,” he added pointedly. “He brought this guy [Herlin Riley] in and said ‘This guy is the tambourine player for traditional New Orleans music.”

Zeroing in on something as seemingly tangential as the right tambourine player for a given track is just another manifestation of the meticulousness with which Simon has always approached writing songs and making records. It’s also evident on the farewell tour, which has been earning adulatory reviews since it opened in May in Vancouver, and which included three nights that month at the Hollywood Bowl.

“The Hollywood Bowl [opening night] show is the only show where I was actually nervous, which is unusual for me” he said. “First of all, it was cold, and that made it tough for the musicians to play. And the Hollywood Bowl can be a really big, tough room to play. The second and third nights were better.”

It took nearly a month into the tour for him to re-embrace perhaps his most beloved composition, “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” and insert it into his farewell tour repertoire. On tour, he has told audiences it feels like he has reunited with a long-lost child.

“That’s one of the pleasures of this tour — singing ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water,’ which I can’t ever say I had a good time singing,” he said. “I didn’t sing it very often, but when I did I never felt like I found the right way of doing it. But this felt good, with yMusic, with that West African [element to the new arrangement]. As I’ve said, my relationship to that song is very odd, because I gave it away so quickly. Even as I wrote it, I said, ‘Oh, this will be for Artie.’”

To say nothing of the dozens, perhaps hundreds, of other singers who’ve subsequently recorded it after Simon & Garfunkel released it in 1970 on the album of the same name. The work swept the Grammy Awards that year for song, record and album of the year honors.

These are the things Simon is reflecting on as he draws his touring career to an end, and perhaps his life as a recording artist as well after “In the Blue Light” is released as the equivalent to a coda on that career.

“After I finished the ‘Stranger to Stranger’ album” in 2016, I thought, ‘I think I’m done,’” he said. “I don’t think I ever said that before. But my feeling was, I don’t think I can do any better than this.”

“I think I can do this just as well,” he said of the potential to keep touring and recording, “but I don’t think I can do better without dismantling everything I know and beginning again, building up another skill set of some kind.

“But I don’t see the purpose; I don’t see the point. It would take many years to do that, and I’d rather see India. I’d rather travel. It usually takes me three years to make each album, and would this be the best use of the next three years? I think it would be better to stop.”

As he views it from the vantage point of his 76 years, it’s not about weighing what’s best for his career.

“David Bowie was working on his final album right up until he died, and I thought, ‘Man, that was great marketing — he really believes in show business,” Simon said. “If I don’t, I don’t think that makes me any less of an artist.”

David Bowie was working on his final album right up until he died, and I thought, ‘Man, that was great marketing — he really believes in show business.’

— Paul Simon

Still, the prospect of walking away not only from touring — which a growing number of veteran musicians are doing at least in part because of the physical demands — but also recording and even songwriting, activities to which Simon has devoted himself professionally for more than six decades, is something other musicians find impossible to imagine, much less carry out.

But as with most aspects of his life, it’s something to which he has put in a great deal of thought.

“It’s not the first time I’ve thought that music might not be an end in itself, but might be a vehicle that deposits you at a certain place and then you go from there,” he said. “Because it certainly can take you, and has taken me, a loooong way. It really gives you a lot of information.

“It’s a really good teacher,” he said. “And I have the good fortune of it being something that was intensely pleasurable for me, something I just loved. So I was educated by something that I loved. But as I say, when I finished that [‘Stranger to Stranger’] album, I felt something like, clack! ‘You’re done.’ And this seems like a really good adventure, one that I should do.”

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.