Bob Hope gets little thanks for all the memories

- Share via

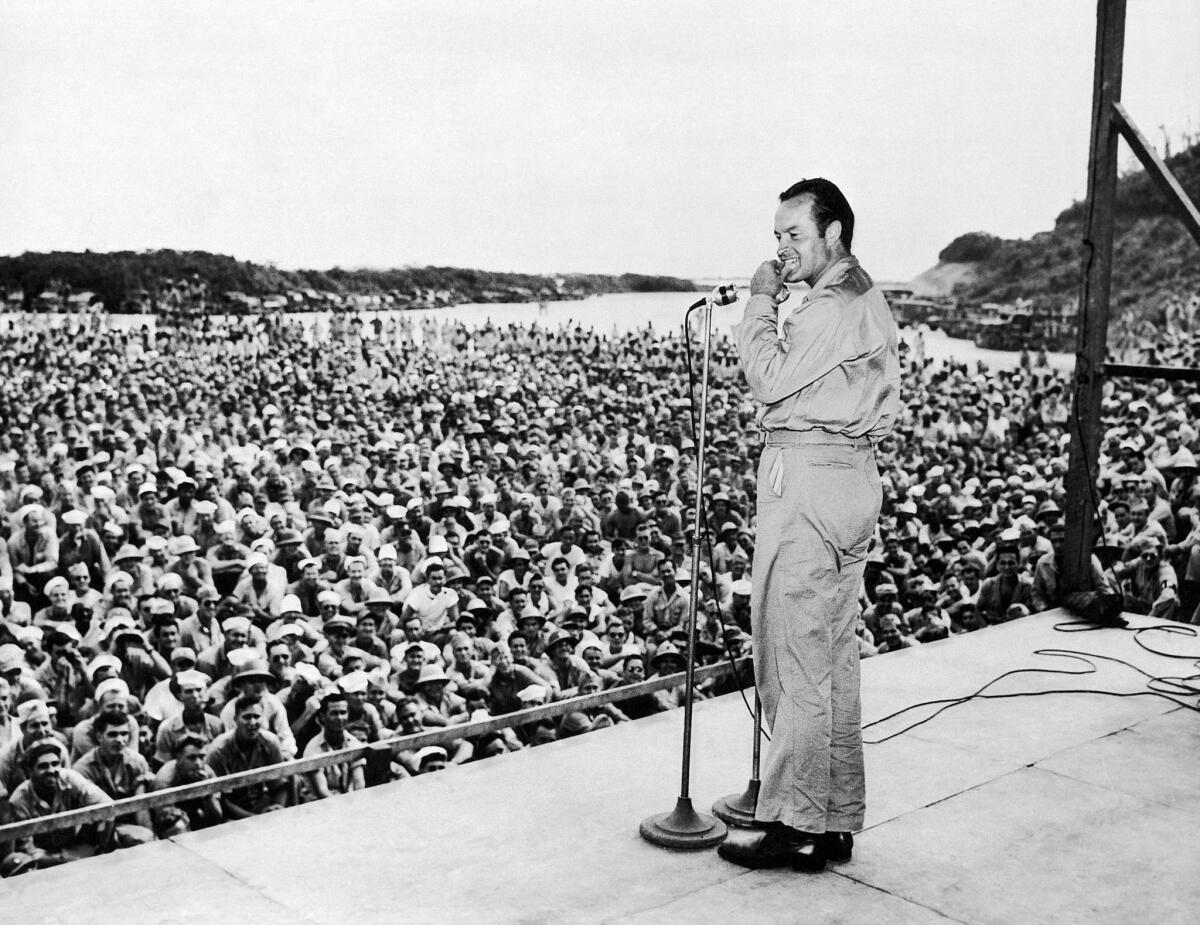

To the boomer generation, seeing Bob Hope on TV or in the movies was like spending time with cranky relatives. Sure, there were a lot of great memories — the World War II shows, the “Road” movies with Bing Crosby — but it also was a little stale, and the jokes, well, they were ancient or worse.

It was easy to forget that for decades Hope was the kinetic king of comedy who conquered every form of entertainment in his path, including vaudeville, Broadway, radio, movies and TV.

In May 1993, NBC threw a lavish birthday party for Hope, who had been a mainstay of the network since the radio days of the 1930s. It was a national celebration featuring such guests as former President Ford, George Burns and Johnny Carson.

Filled with clips and reminisces, “Bob Hope: The First 90 Years” was a valentine to the former Leslie Townes Hope, both funny and emotional, especially when veterans recalled their memories of Hope tirelessly — and courageously — performing for them near battlefields.

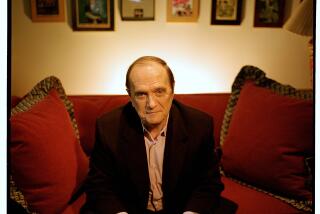

But two decades after the Emmy Award-winning special and 11 years after he died at the age of 100, Hope is something of a forgotten figure.

There are no major retrospectives of his delightful early movies, even the freewheeling “Road” comedies. Hope was the host of the Academy Awards — he did it 18 times — and his snappy patter kept the ceremony breezy and light, but he’s rarely mentioned when people think of great hosts today. His conservative politics and out-of-style humor — sometimes aimed at gays and the ‘60s antiwar generation — put him out of favor with liberal Hollywood and with younger audiences.

So it seemed to Richard Zoglin, the author of a heralded new biography, “Hope: Entertainer of the Century,” that the time was right to restore Hope to his rightful place in the show biz pantheon. While not overlooking his personal and professional transgressions, the book makes a strong case for Hope as a remarkably versatile and surprisingly edgy performer who transformed comedy.

Zoglin, a Time magazine writer and critic, had long wanted to do a biography on Hope. But what cinched the deal was interviewing comedians for his first book, “Comedy at the Edge: How Stand-Up in the 1970s Changed America.”

“I interviewed all of these guys up through Jerry Seinfeld and would ask them who they were influenced by, who they grew up listening to and liking. If they didn’t say Lenny Bruce, they would talk about Jack Benny or Groucho Marx. Nobody mentioned Bob Hope. I thought that shows just how off the radar this guy is.”

That didn’t sit well with Zoglin, who argues Hope, essentially, invented the stand-up comedy art form.

“I kind of discovered he was more important than I thought,” Zoglin said in a recent interview. “He was the first guy on radio to do topical monologues and do more than just vaudeville shtick. He said to his writers, ‘Read the newspaper and give me jokes about what’s going on’ or from his real life. He was the only guy in radio who was doing jokes about things happening in the real world. That was a radical thing.”

Zoglin also gives Hope his just due as a movie star. After appearing in some comedy shorts in the early 1930s, Hope made his feature debut in 1938’s “The Big Broadcast of 1938,” in which he introduced what would be his signature tune, “Thanks for the Memory.”

But his career really took off with 1939’s horror comedy “The Cat and the Canary.” It was the first time he played the brash, wisecracking coward who loved women but was putty in their hands. And he continued to hone that character — which Woody Allen cites as his influence for his own screen personality — in such hits as 1940’s “The Ghost Breakers” along with the series of highly popular “Road” movies.

“They were not great films, but Hope is great in them,” Zoglin said.”You can see how focused he is as performer, how in character he is all the time. He’s good physically, and verbally he’s absolute perfection.”

To noted film and TV historian Stan Taffel, Hope “was as perfect as Chaplin was. He knew where the camera was, and he knew how to pose for the camera. He didn’t take his character so seriously, so we could have fun with it. I think his movies in that era are the best things he ever did.”

One of the reasons Zoglin believes Hope’s legacy has diminished over the years is that “he just stayed around too long.”

Beset with hearing issues and eye problems, which forced him to use cue cards, his later NBC specials were tired and lacked spontaneity. His films from that time period, such as 1966’s “Boy, Did I Get a Wrong Number!” with Phyllis Diller, were painfully wheezy.

Hope, noted Taffel, “had to have an audience all the time. That’s why he ended up staying on TV longer than he should have.”

He also had alienated a lot of viewers during the Vietnam War. Though his specials of his Christmas tours of the troops scored high ratings, Hope misjudged the shift in the culture. And for the first time, Hope, who was good friends with President Nixon, took a pro-war stand.

“That is where he went wrong,” Zoglin said. “He was so sure that we were doing a good thing over there in Vietnam. He had been convinced by the generals he met over there that the military was being hamstrung by politicians and if we went all out, we could win this war in a couple of months. He hated that there were protesters out there picketing. He was from the World War II generation. He started speaking out. He would bad-mouth protesters.”

The Hope portrayed in the biography is a complex man of deep contradictions. He carefully cultivated the persona of Bob Hope and rarely revealed much of himself in the process. He was notoriously frugal, but generous with his friends and relatives when they needed help. Though married for nearly 70 years to Dolores Hope, he was a chronic adulterer who had affairs with actresses, showgirls and others.

“I don’t think he was an introspective guy,” Zoglin said. “I think he was the last guy in Hollywood you can imagine walking into a therapist’s office. He didn’t have that gene of self-examination. He never let down his hair and revealed himself.”

Zoglin also discovered the reason why Hope, who immigrated to Cleveland with his family in 1908 from Britain, dropped out of high school during his sophomore year — he was sent to the Boys Industrial School, which was a reform school.

“It shows how good he was at controlling his life story from the very start,” Zoglin said. “He would write these jokey memoirs, and he loved talking about his scrappy childhood in Cleveland, and he would even allude to shoplifting sometimes, but never the reform school.”

The biography also reveals that he and Dolores weren’t married on Feb. 19, 1934, in Erie, Pa., as Hope told writers. In fact, Hope was still married to his first wife, who had been his vaudeville partner until November of that year. (The Hope family cooperated with Zoglin, giving him access to the comedian’s private papers.)

Though his personal life was flawed, as an entertainer he had few peers.

Zoglin noted that Hope realized “what being a celebrity is about and what that means to his fans. I think he understood that better than any star.” For example, Hope answered a “higher proportion of his fan mail than anyone else. Not that he didn’t have a battery of assistants, but he had to be dictating those because he had so many personal comments in there.”

And though he played a coward on screen, Hope risked his life several times to entertain the soldiers. Only three days after Gen. George Patton and his troops entered Sicily, Hope and his show arrived to perform.

“They were still getting bombed by the Germans,” Zoglin said. “When you hear a war correspondent like Ernie Pyle say ‘I was in two of those raids with Bob Hope and believe me, they were bad air raids,’ you know they were bad. It was very brave what he did.”

Follow me on Twitter: @mymackie

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.