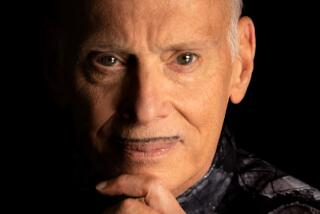

Hughes was a master of light, right notes

- Share via

Filmmaker John Hughes burned brightest in the ‘80s, when he defined teen angst in terms of the caste system of the suburban high school experience, a thread that others would pick up again and again.

His films were talky, in a good way. Like the kids whose stories he was telling, he let them ramble. Teen self-absorption was treated with reverence, not ridicule. The world might make fun of them, their classmates, their brothers and sisters too, but never John Hughes.

And a generation of kids and future filmmakers like Kevin Smith and Judd Apatow embraced it.

Hughes, who died Thursday at age 59, was fascinated with the human as outsider. Outsiders like “Pretty in Pink’s” Molly Ringwald who just wanted to fit in. And outsiders who couldn’t care less: Matthew Broderick as Ferris Bueller on his legendary day off, Judd Nelson’s not quite broken Bender in “The Breakfast Club,” Anthony Michael Hall’s martini-mixing geek in “Sixteen Candles,” all members of the players club before they were 17.

But Hughes’ outsiders lived in a different part of town than, say, Francis Ford Coppola’s gritty, wrong side of the tracks “The Outsiders.” Hughes outsiders were white, comfortably middle-class and probably from one of Chicago’s affluent suburbs, where he grew up and returned in the ‘90s when he’d had his fill of Hollywood. Things were only slightly sad or bad in his films, there were no serious train wrecks -- only feelings got hurt, and the endings were usually happy ones.

He reflected a very specific slice of Americana that like many, I understood. A pop culture filmmaker adored in the heartland, he knew how to hit all the light notes - an easy sentimentality, a measured angst, an outrageous sense of fun. His was a spoon-full-of-sugar kind of filmmaking that was often exactly what I wanted, if not what I needed.

The slights that life hands us was one of his favorite playgrounds. Forgotten birthdays, forgotten kids, forgotten families -- “Sixteen Candles,” “Home Alone,” “Planes, Trains & Automobiles” -- someone was forever being overlooked.

When you’re Ringwald, and a soft, pouty, still awkward 16, it hurts; when you’re an 8-year-old screaming terror embodied by Macaulay Culkin, it’s the best Christmas gift ever; and when you’re John Candy’s middle-aged lonely traveling salesman in a life where nothing, including the suit, fits, it’s tragic.

For a period of time, Hughes was so dominant -- certainly in the U.S. where he always played best -- that it’s hard to believe that he only directed eight films. He wrote 30 others -- the “Home Alones,” most notably -- that were produced, 16 of them in the ‘80s, 13 in the ‘90s, and contributed characters or ideas to a handful of others.

Of all of his films, there are two that will forever be quintessentially Hughes for me: “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” absolutely swimming in attitude, which captured brilliantly and irritatingly the kind of cockiness that you envy as a teen, hate as an adult, recognize no matter what age you are, and “The Breakfast Club,” life deconstructed in high school detention, the archetypes and the anxiety playing out in real time.

By “Curly Sue” in 1991, Hughes had apparently tired of fighting battles with studio executives who second-guessed him.

He left Hollywood behind and headed back to the Chicago area, where he would still dabble in the business from a distance.

But really, Hughes was a creature of the ‘80s, and if he hadn’t left Hollywood, it was on its way to leaving him.

Comedy took on more of an edge, went raunchier, darker, meaner than Hughes ever could.

In the end, like so many of the characters he created, Hughes had become a cinematic memory stream of another time when things didn’t seem so bad.

I will light 16 candles and remember.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.