Bunker Hill once was a neighborhood. Then progress came to town

- Share via

In an early scene from “The Exiles,” Kent MacKenzie’s moody 1961 film about the lives of a group of indigenous people living in Los Angeles midway through the 20th century, a young woman carries a bag of groceries up a hillside street flanked by weathered Victorian houses converted into apartments and boarding houses.

The shot is sumptuous: a play on shadow and light and the geometries of the once-graceful homes that lined the streets of L.A.’s Bunker Hill. “The Exiles,” as Times film critic Kenneth Turan noted in a 2008 review, “captured a brooding picture of a darkly beautiful, long-gone Los Angeles.”

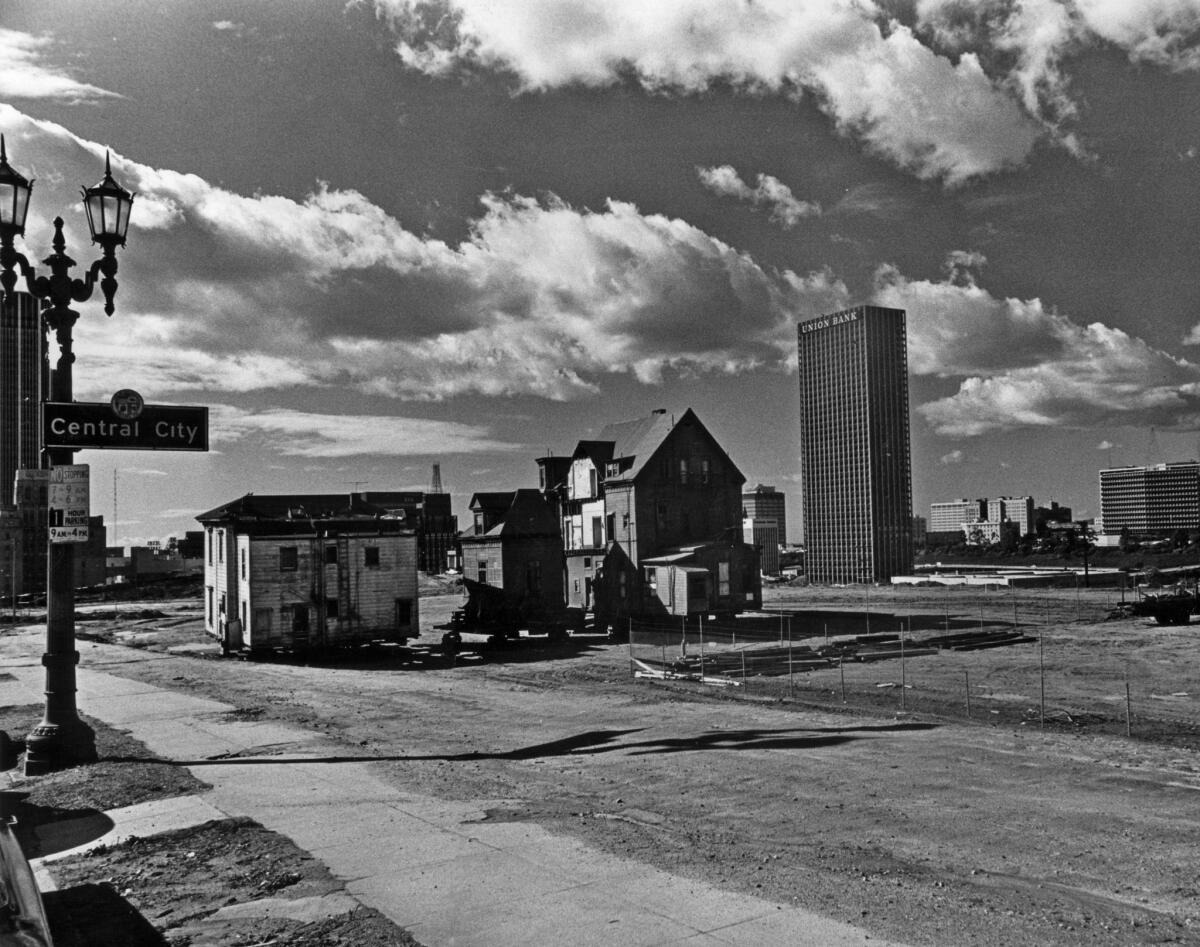

Indeed, that Los Angeles is long gone. Clay Street, the narrow thoroughfare where Yvonne Williams, the young Apache woman who serves as the film’s heart, was seen carting her goods, no longer exists. Neither do any of the Victorian buildings that once lined the street. Like the rest of old Bunker Hill, the street was demolished during an infamous pique of 1960s “slum clearance” policies that saw the entire neighborhood leveled to raw earth.

FULL COVERAGE: Grand Avenue project »

Today, the sliver of Clay Street where MacKenzie filmed subtly alluring scenes is occupied by Angel’s Knoll, the shuttered, unkempt park that occupies a patch of steep hillside at Grand Avenue and 4th Street. On a recent afternoon, one of its more remote corners was inhabited by a gaunt man slipping into an opioid nod.

All of this lies just a couple of blocks over from Grand, where two internationally famous museums — the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Broad — stand alongside several performance complexes, including the Music Center, the Walt Disney Concert Hall, the Colburn School and REDCAT, all representing different eras of Bunker Hill revitalization.

Indeed, every few years it seems that a major civic or commercial development opens atop Bunker Hill, leading to ample media coverage. The Music Center, which opened in stages, starting in 1964 — around the same time the city was bulldozing the last boarding houses that sheltered elderly and immigrants — has been described as the project that “commenced the revitalization of Bunker Hill.”

When Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall opened on Grand Avenue in 2003, it was described as “the centerpiece of revitalization.” Developer Eli Broad once described his ambitions to transform Grand Avenue into “the Champs-Elysées of Los Angeles” — “which may have been an exaggeration,” he later said.

From the Archives: The Castle on Bunker Hill »

Now as construction begins on Gehry’s Grand Avenue project — the mixed-use retail and residential complex that will occupy the dour parking lot that has, for years, sat across from Disney Hall — there is renewed chatter about “revitalization.”

But what does it mean to “revitalize” something that we had a hand in extinguishing? Bunker Hill was a vital neighborhood that was dismembered by city, state and federal policies, then reassembled into corporate superblocks by private developers.

The neighborhood’s roots took hold when a pair of early moguls — Prudent Beaudry and Stephen Mott, for whom streets are named downtown — acquired much of the land in the 1860s. By the late 19th century, the neighborhood was a bastion of the well-to-do, draped in extravagant Victorian houses and Beaux Arts apartment buildings.

In the early 20th century, as more fashionable districts emerged west of downtown, the wealthy moved with them. By the 1920s, Bunker Hill had transitioned into a lively working-class neighborhood, the broad wooden porches of the Victorians beckoning transplants from Mexico, Europe, the Midwest and a multitude of indigenous reservations, as seen in MacKenzie’s “The Exiles.”

Rather than improve the lot of the working poor who inhabited the areas — 1 in 5 of whom were foreign-born, primarily in Mexico, according to the U.S. census — the city set out to get rid of them. By the time the Depression steamrolled in, plans were already being floated to remake Bunker Hill.

ALSO: Architect Frank Gehry unveils designs for long-delayed Grand Avenue project »

One enterprising local developer proposed razing the entire hill with hydraulic mining equipment, since it was “a barrier to progress in the business district of Los Angeles.” This was followed by countless other plans to “modernize” the neighborhood. As critical theorist Norman Klein notes in “The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory,” his 1997 book exploring the ways in which L.A. has continuously reinvented its landscape, “no ethnic community downtown was allowed to keep its original locations: Chinatown, the Mexican Sonora, Little Italy.”

The path for Bunker Hill’s ultimate undoing was set with the 1949 federal Housing Act, which allowed for a looser use of eminent domain. In 1959, the City Council voted for the Bunker Hill renewal project that would “keep our city from slipping backward, like San Francisco and New York in the population race.”

The plan: The government would acquire every property on Bunker Hill through eminent domain, evict the elderly and the immigrants who lived there, demolish everything in sight, then turn the land over to private developers. Within a decade, the last Victorian mansions on Bunker Hill were carted off to Heritage Square, where they promptly succumbed to arson.

The rebuild took decades — and is underway still.

When Klein came from New York to Los Angeles in the early 1970s, he thought Bunker Hill felt “very bald” — “like a person who has a big bald patch and a big fat head … like some of the architecture there is trying to cover up the bald spot.”

Certainly it’s an architecture that is trying to compensate for something.

To walk the length of Grand Avenue, from Temple to 5th Street, is to immerse yourself in a tour of the monumental: Rafael Moneo’s cathedral (a medieval Spanish castle rendered contemporary), Gehry’s Disney Hall (an ebullient sailing ship) and Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Broad museum (aka the cheese grater).

It is also to immerse yourself in corporate development projects that are actively hostile to the street, impassive glass towers whose policed private-public spaces lie above or below grade — impervious to happy accident, human scale or the sight of a half-naked hippie playing the bongos. As Mike Davis describes its structures in “City of Quartz”: It is “a Miesian skyscape raised to dementia.”

Review: L.A.’s ‘Exiles’ revisited »

This makes it a curious location for L.A.’s most important cultural hub. Culture is often at its most dynamic when it is pushing boundaries, cropping up unexpectedly in in-between spaces. The design of Grand Avenue, with its string of large-scale institutions, has left little room for this.

Not that there aren’t moments of L.A. scrappiness: an artist staging a performance on the plaza before MOCA, nighttime dance shows on the steps of the Music Center, experimental multimedia shows at REDCAT, which has served as a bastion of emerging artist culture on this very corporate strip. But culture on Grand Avenue is largely top-down. And this has overwritten a place where ideas once bubbled up. Could a budding John Fante peck out his novel on today’s Bunker Hill? Probably not.

The erasure of Bunker Hill as it once stood has generated “a kind of schizophrenia,” says the voluble Klein. “It has made it difficult to understand the city.”

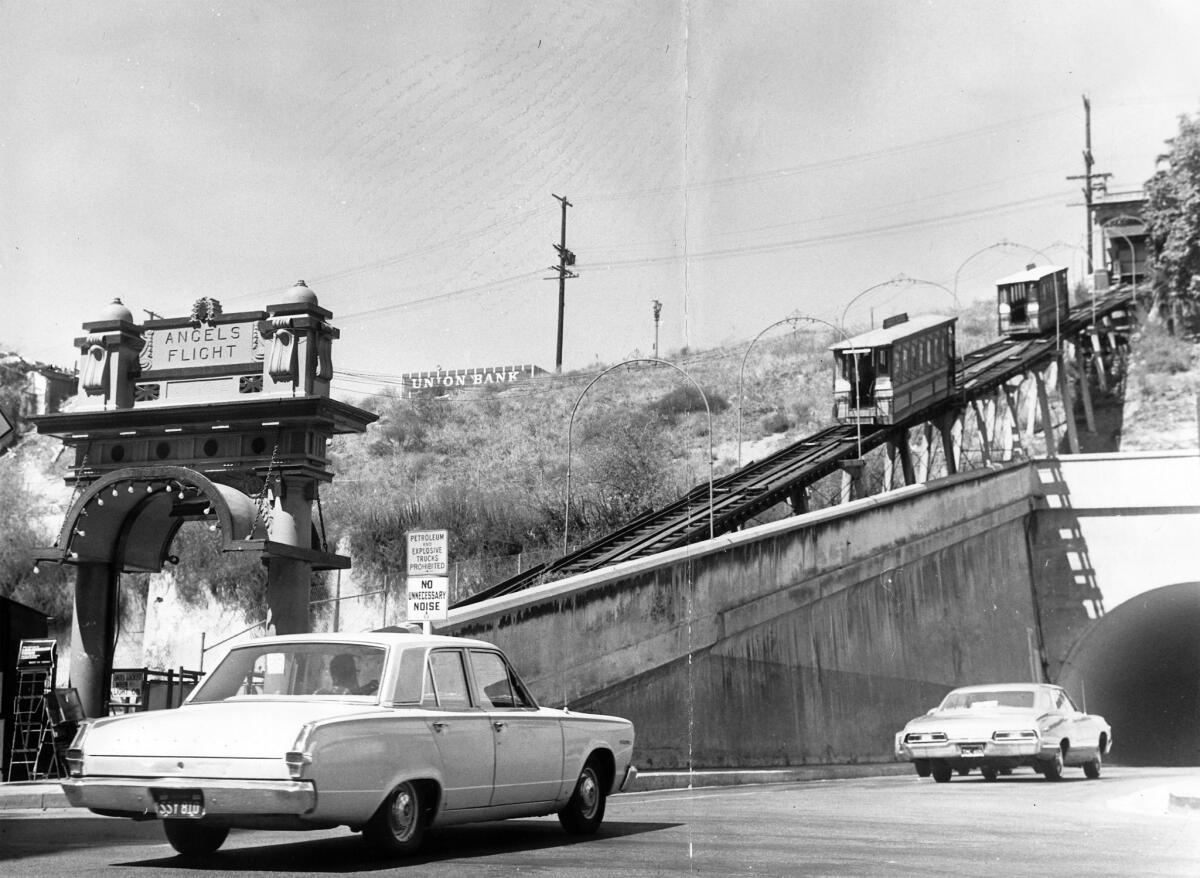

The quaint Angels Flight funicular, which opened in 1901 and ran alongside the 3rd Street tunnel, once connected residents of Bunker Hill to the city below. After redevelopment, it was relocated a few hundred feet to the southwest and now hauls office workers to the Postmodern corporate plazas on Grand Avenue — a relic from another era, its original significance and purpose lost.

In “The Exiles,” there is a scene where the camera settles on a bar called El Progreso — the Progress. Progress can be a curious thing. Progress for some can mean erasure for others. Like the old Bunker Hill, El Progreso is also gone.

ALSO: Last House in Bunker Hill Razed »

[email protected] | Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.