In 2017, an angry public demanded the removal of controversial art works. Could the debate limit artistic freedom?

- Share via

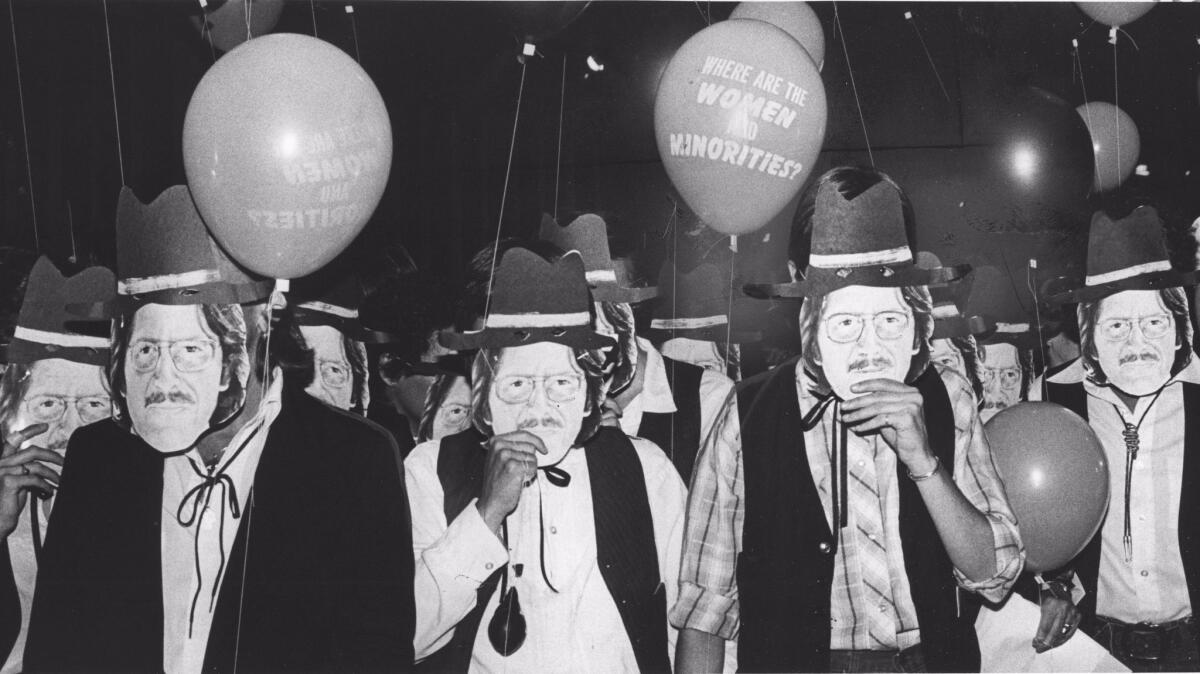

The protesters arrived two by two, wearing black suits and face masks that bore the face of the museum’s curator of 20th century art.

It was the summer of 1981 and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art was celebrating a trio of exhibitions marking the city’s bicentennial with a Champagne reception interrupted by more than 100 protesters carrying gray and pink balloons that read: “Where are the Women and Minorities?”

Standing out from the black-clad protesters in masks bearing the visage of LACMA curator Maurice Tuchman, were six women in pink cowgirl outfits. They unfurled a banner that read “The Los Angeles County Museum of White Male Art.” One of the bicentennial shows, “Seventeen Artists of the Sixties,” included neither women nor people of color. Another included only two women and no artists of color.

The present: It’s like the past — only different.

In 2017 there was no shortage of questioning — not just of institutions, but of individual artists and the subjects they aim to present.

Stoked by the dissemination powers of the internet, this year was a maelstrom of debate about who wields power, how gender is represented and how artists contend with that third rail of American society: race. It was a reckoning for institutions that have been slow to contend with issues of diversity. But it’s a pendulum swing that also threatened to limit the freedom with which artists and writers conceive and experiment.

In March, at the 2017 Whitney Biennial in New York City, protests broke out over “Open Casket,” a Dana Schutz abstraction painting inspired by the infamous 1955 coffin photo of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old African American boy who was brutally lynched after a white woman falsely accused him of flirting with her.

One protester at the biennial’s opening stood before the work in a T-shirt that read “Black Death Spectacle.” British artist Hannah Black posted a letter online that demanded the work be removed and destroyed.

“It is not acceptable for a white person to transmute black suffering into profit and fun,” she wrote.

Many supported Black’s call. Others, such as artist and critic Coco Fusco, argued against it on the grounds that it constituted censorship.

“We may understand artworks to be indicators of racial, gender, and class privilege — I do, often,” she wrote in Hyperallergic. “But presuming that calls for censorship and destruction constitute a legitimate response to perceived injustice leads us down a very dark path.”

A similar controversy erupted around “Scaffold,” an outdoor sculpture by Sam Durant presented at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The Los Angeles-based artist’s work served as a representation of seven gallows used in historic U.S. government executions, including that of 38 Dakota men in Mankato, Minn., in 1862.

Native American activists protested, stating that “Scaffold” trivialized a brutal episode in indigenous history. “It’s not art to us,” one activist told the Minneapolis Star Tribune. After a meeting with Dakota elders in June, Durant agreed to remove the work and sign over intellectual rights to the piece. The wood employed in the sculpture was later buried in a secret location.

Protests in other cities and online have demanded the removal of other works, too.

In September, the Guggenheim Museum withdrew three pieces from a show on 1990s Chinese art over concerns about animal cruelty. This included a 2003 video of fighting dogs strapped to treadmills futilely attempting to attack each other and Huang Yong Ping’s “Theater of the World,” a caged arena featuring lizards, insects and snakes. During the exhibition, some of the animals would die as they were consumed by larger species.

In the wake of sexual harassment allegations dominating the news, a pair of artworks — one in L.A., another in New York — also ended up on the firing lines.

Erika Rothenberg’s “The Road to Hollywood” installation at the Hollywood and Highland Center, had a chaise longue element removed by mall management after the piece was erroneously described as a “casting couch.” (It was later returned.)

This month, an online petition was launched to remove a painting by Balthus — “Thérèse Dreaming,” 1938, which shows a girl sitting with her open legs, revealing some underwear — from the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the grounds that the painting romanticizes “voyeurism and the objectification of children.” The Met declined to remove the painting, stating that its presence provides an opportunity for reflection “on both the past and the present.”

FULL COVERAGE: Year-end entertainment 2017 »

A number of these cases have raised questions of censorship. Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei, for example, decried the Guggenheim’s decision to withdraw its pieces. “When anyone uses a moral high ground to judge an art exhibition and to demand the withdrawal of contents that may or may not violate those rights,” he told this paper’s Deborah Vankin, “it presents a potential danger of violating the freedom of speech.”

Also concerning is that social media outrage, delivered in 140 (now 280) character increments, seems to flatten all nuance.

Schutz’s painting of Till, described as a vehicle for a white artist’s fame and fortune? It was never for sale.

The animals that would eat each other at the Guggenheim? They were bred for pet consumption — which means their fate at the museum would have been no different from what they faced in a suburban kid’s boa tank.

And the “casting couch” in Rothenberg’s “Road to Hollywood”? It was not intended as a tool of “rape culture,” as one offended viewer alleged online, but as a place groups of people could gather for a photo before the Hollywood sign in the distance. (Rothenberg discussed its purpose in a 2010 lecture at Otis College of Art and Design.)

The debate surrounding the French Polish surrealist Balthus has likewise stripped context from the artist’s admittedly controversial work. Balthus painted a lot of prepubescent girls. He also painted his wife to look prepubescent. And he painted portraits and landscapes.

Was his work featuring girls disconcerting? Yes. Balthus cast a male gaze on girls in the fit of life’s changes. But he also succeeded in conveying what it meant to be in the thrust of those changes. In “Thérèse Dreaming” I’ve always seen a little bit of myself: a young girl relentlessly told to “sit like a lady” enjoys a private moment in which she doesn’t have to conform to the rules that govern her body.

The nature of the debate on these issues threatens to constrain artists at a time when a multiplicity of voices and subjects is what’s needed.

— Carolina A. Miranda

A painting can have more than one meaning.

The debate that fills me with the greatest ambivalence centers on the frequently posited idea that only certain artists should be allowed to tackle certain subjects. A sign protesting Durant’s work at the Walker read “Not Your Story.” In a social media post about Schutz’s “Open Casket,” one artist wrote: “the subject matter is not Schutz’s.”

These critiques rise from issues of inequity that have long plagued museums. White artists and white curators, usually male, are historically the ones who have told the story of art. Much like that 1981 LACMA exhibition that purported to outline the turbulent 1960s entirely through the lens of white men.

Inequity undoubtedly persists — less than a third of solo shows at major museums in the U.S. go to women. But the nature of the debate on these issues threatens to constrain artists at a time when a multiplicity of voices and subjects is what’s needed. If white artists should stick to whiteness, should black artists stick to blackness? As a Latina, should I write only about Latinos? As the daughter of South American immigrants who was born in Wyoming, is my range further limited?

These are constraints I fiercely resist. First, because race and culture intersect in ways that are blurry and difficult to define. Second, because I’ve spent much of my career struggling against newsroom typecasting. As a writer — an art form of sorts — I am here to engage a full palette of concepts and ideas, not just the ones that pertain to my identity. Artists of all colors and genders should demand the same.

We may not always like the results. We may protest them in masks. We may critique them in essays. We may tear them apart 280 characters at a time. But let’s allow for the messiness and the mistakes. It’s from those moments in which new ideas about culture are born.

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

Best art in 2017: Our critic’s top 10 exhibitions, plus one very big worry

For American cities in 2017, flood, fire and volatility became the new normal

Classical music in 2017: After an astounding year, the L.A. Phil deserves a top 10 list of its own

Tweets, sexual abuse and racial divides shook the entertainment industry and beyond in 2017

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.