Appreciation: To be a writer in Los Angeles is to contend with the words of Jonathan Gold

- Share via

My earliest memory of Jonathan Gold involves stalking him.

About six years ago, I was a freelancer — working on a chapter about the history of Peruvian restaurants in the Western United States for a small academic press in Lima.

I had spent countless hours sorting through mountains of articles on Peruvian food from West Coast newspapers dating back to the 19th century. Most of the writers were clueless. (One critic took issue with the quality of the bread at one Peruvian restaurant — perhaps unaware that Peru isn’t a wheat culture.)

And then there was Jonathan Gold. His reviews of Peruvian restaurants were not just well-informed (he understood the highly regional nature of the cuisine), they were lucid and funny.

“Chicharrón de pollo is something like Peruvian Chicken McNuggets,” he once wrote of Mario’s Peruvian Seafood in the LA Weekly, “heavily breaded chunks of bird fried hard to resemble pigskin and served with an herbed, citric dipping sauce as vividly yellow as a happy-face emblem.”

I was determined to interview him.

At the time, I knew Jonathan through his work but the closest I had come to meeting him were the exchanges we’d had on social media about L.A. hot topics such as the “porno burrito” — the forearm-sized Super Burrito dispensed by the now-defunct El Atacor #11 in Glassell Park.

When I reached out about an interview he’d responded with graciousness, but I could never pin him down on a time (a phenomenon his editors were intimately acquainted with). One day, a friend who worked at KCRW gave me a heads up — Jonathan was due at the station the following Monday to record a segment for “Good Food.”

On that day, I parked myself in a basement corridor for hours until he showed up.

Little did I know then that he’d serve as an informal reference when I was hired by The Times 18 months later — by his wife, editor Laurie Ochoa.

With Jonathan’s death, we lose a piece of Los Angeles, but we also lose a role model critic — whose influence and influences extended well beyond the world of food.

Jonathan was a punk cellist who studied music at UCLA. He was a performance artist who once got naked with a chicken. He was an assistant to seminal Los Angeles conceptualist Chris Burden. He was a prolific music writer — Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre dubbed him “Nervous Cuz.” And he just happened to like food. Very much.

He was also a writer who had a way of busting through criticism’s most self-referential tendencies to draw the larger world in.

Of the Hollywood hangout Chasen’s, he once wrote that it was “a swell place to celebrate a 75th birthday or a Contra incursion.”

In a review of a dessert sampler that featured high-end versions of Rice Krispie treats and Hostess Sno Balls, he remarked, “Many of the finest artifacts of American culture in the last decades have come from the collision of formidable technique and trivial obsession. Bill Irwin’s juggling comes to mind, as do Jeff Koons sculptures and Peter Sellers’ setting of ‘Don Giovanni’ outside a Harlem crackhouse.”

In one sentence about food, a reference to a clown, a sculptor and an opera director.

Jonathan was the deft wordsmith who knew how to pry criticism out of its stuffy silos. He was never just writing about food. He was writing about culture. He was writing about Los Angeles. He was writing about who we were at a given moment in time. And he did it in ways that that were both erudite and joyous — his glee over a good dish was always infectious.

He was a writer who had a way of busting through criticism’s most self-referential tendencies to draw the larger world in.

Over the years, I had the good fortune to get to know Jonathan on a more personal level. I tagged along on trips that became restaurant reviews of farm-to-table French and Filipino halo-halo. I got to participate in the dinners he and Laurie regularly held in their home — meals stocked with a fascinating crew of journalists, novelists, photographers, chefs, critics and environmentalists, for whom Jonathan would whip up vats of post-Thanksgiving turkey gumbo or New Year’s Day Hoppin’ John. Somehow I ended up talking about Jonathan’s work in Laura Gabbert’s documentary on him, “City of Gold.”

Being a writer in Los Angeles means continuously contending with the words of Jonathan Gold.

What made Jonathan truly remarkable was the way he quietly advocated for other writers — for me and for others — pushing us to our best tendencies.

When I was first hired at The Times, he pulled me aside and told me that criticism wasn’t just about writing about what you see — it’s about writing about what you’d like to see.

Those are words I continue to take to heart every day.

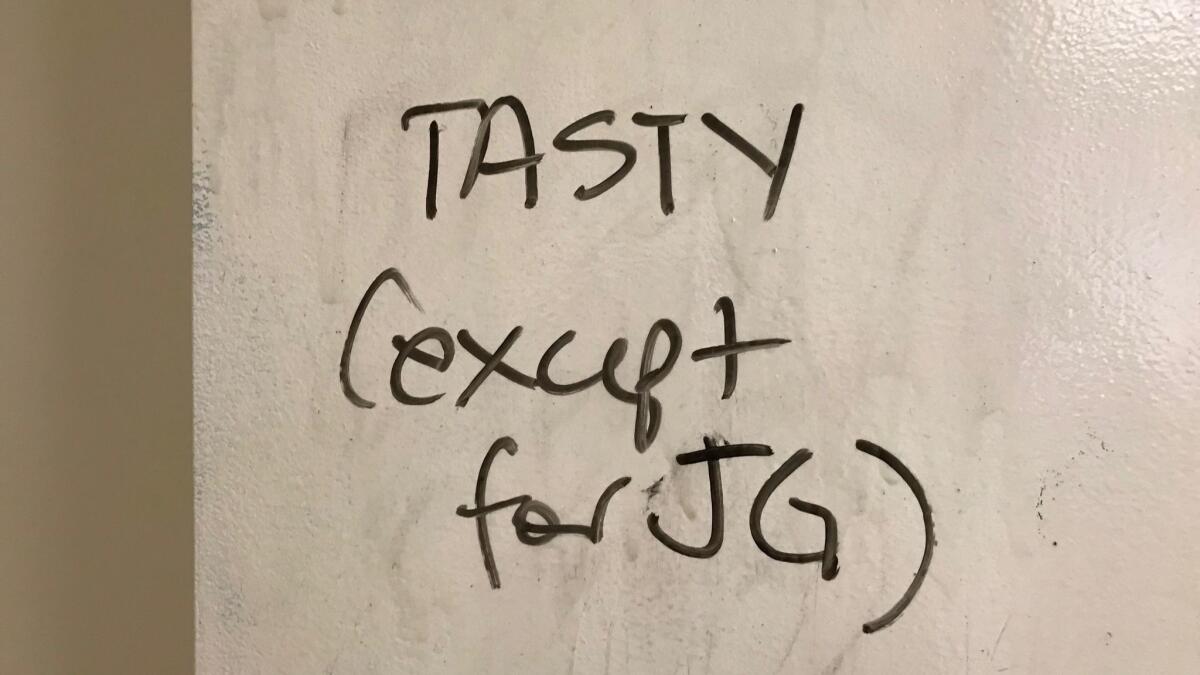

This month, as The Times prepared to leave its downtown building for El Segundo, I spent several days combing the buildings for an architectural piece. One afternoon, I ended up in the food department, where a list of banned words had been scrawled on the wall in marker: “veggie,” “eatery,” “yummy,” “foodie” — all verboten in Times food stories.

Also on the list was “tasty.” Written in parentheses next to it, however, was the phrase: “except for JG.”

“Tasty” can now be retired. Things certainly won’t taste as good without Jonathan Gold.

ALSO

We all live in Jonathan Gold’s Southern California »

View all our coverage of Jonathan Gold | 1960 – 2018 »

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

[email protected] | Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.