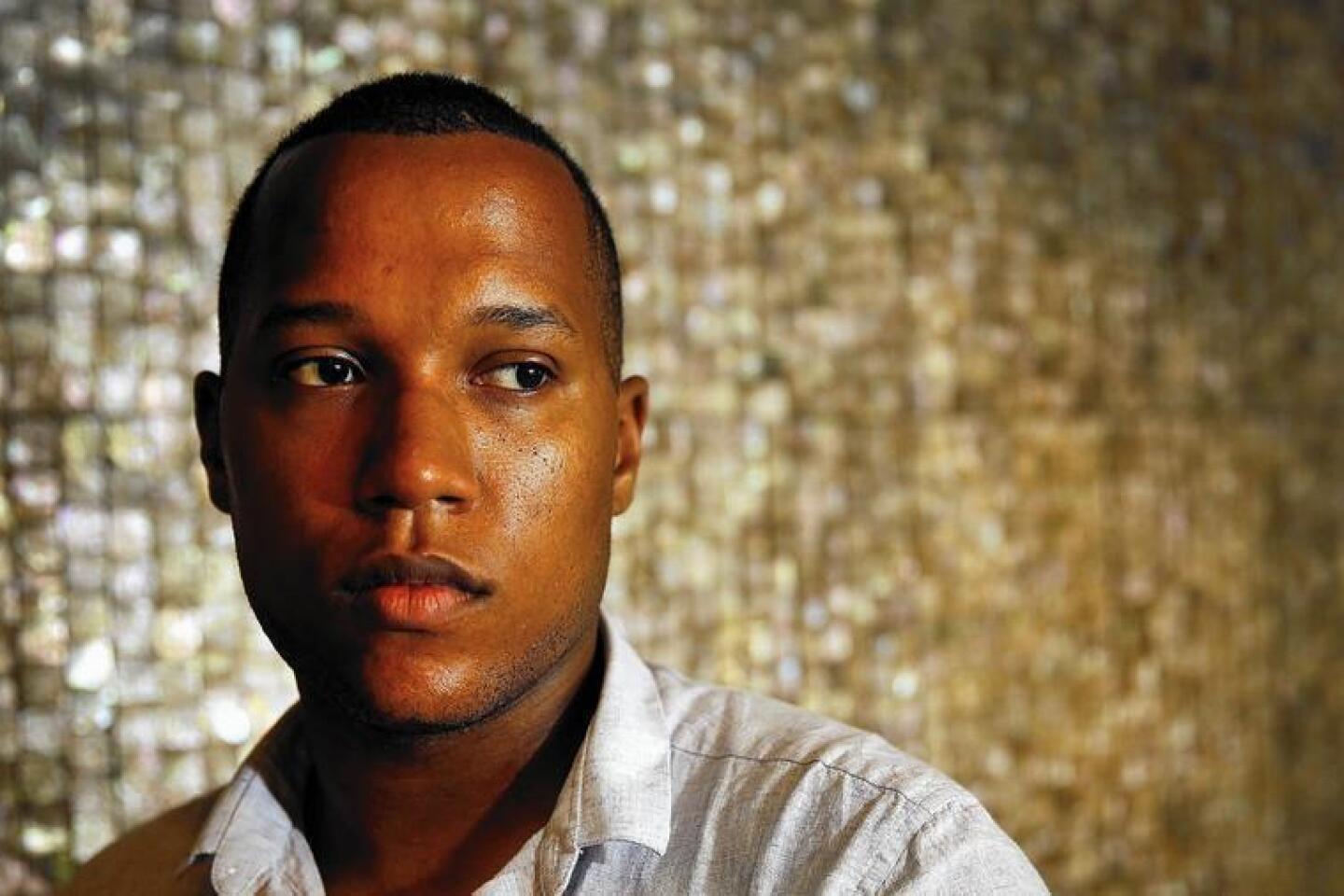

Seattle conductor Ludovic Morlot at the helm of the L.A. Phil for ‘Become Ocean’

Conductor Ludovic Morlot, currently Music Director of the Seattle Symphony, rehearses with the LA Phil.

- Share via

Ludovic Morlot is trying to find the right balance. At the moment, that’s the balance of the three mini-orchestras (brass, winds and strings) of the L.A. Philharmonic, rehearsing John Luther Adams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning symphonic work, “Become Ocean.”

The stage at Walt Disney Concert Hall has more depth than at Benaroya Hall in Seattle, and Adams’ piece thrives on the subtleties of texture and harmonic blend.

“Each orchestra has its own length of waves,” explains Morlot, “starting from nothing, building up to a higher dynamic, and going back to the piano dynamic. By the magic of numbers, there are three times in the piece where the three orchestras reach their maximum dynamics at the same moment. Harmonically, it clashes and provides some real complexity in the colors.”

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

If Morlot sounds like an expert on “Become Ocean” — which the Phil will perform for the first time this weekend, in two matinee programs — it’s because he helped bring it into the world.

Morlot commissioned the 42-minute piece in 2011, when he was Seattle Symphony Orchestra’s freshly appointed music director designate. He gave the work its world premiere in June 2013 in Seattle, the performance captured in the album release on Cantaloupe Records. The Pulitzer jury called it “haunting … evoking thoughts of melting polar ice caps and rising sea levels,” and the New Yorker’s Alex Ross deemed it “the loveliest apocalypse in musical history.”

Conductor Ludovic Morlot, second from left, talks with LA Phil members Carrie Dennis, Martin Chalifour and Nathan Cole after rehearsal.

“I really believe in the power of this music,” Morlot says. “I could say almost surprisingly, because it’s not the kind of vocabulary that I’ve grown up with. The whole piece is a big meditation on tides of existence.”

He witnessed an interesting phenomenon when he took it to Carnegie Hall last spring. “The audience is a little puzzled as to how to listen to it. It really starts working after 10 or 15 minutes, when they decide not to pay attention and understand it, but just let it come to them and experience it viscerally. The minute you give up is usually where the audience gets really quiet.”

“Become Ocean” is one of about 35 works Morlot has commissioned since he took the mantle in Seattle. Composers have included Sebastian Currier, William Brittelle, German sculptor/sound artist Trimpin and Elliott Carter, who dedicated his final orchestral work to Morlot (“who has performed many of my works so beautifully”). Morlot’s aim has been to crystallize the orchestra’s identity through the new music it programs and invests in and to give the entire city a more balanced musical diet.

“As an orchestra, we have the double mission and commitment to be acting as a museum and an art gallery,” he says. “If you look at programming 200 years ago, 80% of the music presented every single night was new music. We fell into a diet that is unhealthy, where now if you have 2% of new music, people get worried. We get worried because we all lost the appetite.”

He’s taken Seattle’s innovative reputation at face value, creating concert series like Untuxed (shorter, more casual programs) and [UNTITLED] — late-night concerts that turn the hall’s lobby into a cozy, informal performance space filled with only new music — as well as Sonic Evolution, which fosters collaboration between the orchestra and area bands and artists across genres. (He also initiated Seattle Symphony’s own record label, which has favored new music in its first seven releases.)

“It’s invited not only younger audiences but from completely different backgrounds,” Morlot says. “That’s why I mix and match. In some concerts you might hear Beethoven and Dutilleux … or Beethoven and John Luther Adams. Our tagline is ‘Listen boldly,’ and I don’t just say that for the conservative audience, to give new music a try. I use ‘listen boldly’ the other way too, because I think it’s very important for people that think they don’t like classical music to actually give it a shot. I mean, imagine what a gift it might be to hear Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony for the first time in your life if you’re 45.”

(Morlot will commence his oceanic weekend at Disney Hall on Friday night with the conservative pairing of Beethoven and Britten — albeit with liberal video accompaniment.)

Seattle has responded. The box office for subscription concerts has seen a 10% bump since 2012, and tickets for [UNTITLED] consistently sell at 80% or more. “Nearly everyone thinks orchestras need to do more to reach new audiences,” says former Seattle Times music critic Melinda Bargreen. “Morlot is putting that belief into action.”

The 41-year-old music director began his journey in Lyon, France, as a violinist. While pursuing a performance degree in Montreal, he sparked to playing the orchestra instead and altered course. He studied conducting in London, then under the likes of Seiji Ozawa and James Levine. He was appointed assistant conductor of the Boston Symphony in 2004 and was soon guest gigging in New York and Chicago.

He took the baton of music director in Seattle in 2011 — a post he’s set to remain in through 2019 — from 26-year veteran Gerard Schwarz and simultaneously served as chief conductor of La Monnaie from 2012 to ’14. (He parted ways with the Brussels opera company last December over differences of “artistic vision” that arose during an X-rated staging of Don Giovanni.)

The shakeup in Seattle has been “more of a gradual evolution than a sudden shift,” says Bargreen. Which comes back to balance.

“I always would like to do it more aggressively,” Morlot says of introducing new music into the city’s bloodstream. “As an artist you just want to be able to do it week after week. So to find the right balance has been the challenge.”

He is relentlessly optimistic about symphonic music. “The orchestra is the heartbeat of the city, so you cannot just let that go. It’s just a matter of what pace you set for the city you live in. And the pace might be 35 beats a minute, or 180. But a city cannot live without that heartbeat.”

ALSO:

Classical music + visuals = intrigue, at UCLA’s ‘Beyond Music’

András Schiff and the L.A. Philharmonic join Haydn for a look at war

Zubin Mehta and Israel Philharmonic Orchestra are not a good fit in the smallish Wallis

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.