Diego Rivera’s Cubist masterpiece arrives at LACMA

- Share via

Two paintings by Diego Rivera, including his 1915 Cubist masterpiece, have joined “Picasso & Rivera: Conversations Across Time,” an exhibition at the

“Zapatista Landscape” (1915) and “Flowered Canoe” (1931) had been on loan to the Grand Palais in Paris for “México 1900-1950: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco and the Avant-Garde.” The sprawling survey closed late last month.

Learning from Pablo Picasso, with whom he socialized during a lengthy sojourn in Paris in the 1910s, Rivera applied the Spaniard’s groundbreaking Cubist style to a riveting representation of Emiliano Zapata Salazar.

Zapata was leader of a critically important peasant revolt south of Mexico City during the Mexican revolution. Rivera applied Picasso’s Cubism — a revolution in seeing — to a revolutionary subject.

His image is loosely based on a widely circulated photograph of Zapata, his hand brandishing a rifle at his side. He wears a broad-brimmed sombrero, a striped serape and cartridge belts crisscrossed over his body.

Rivera’s fractured Cubist planes capture all these scrappy elements in a tight, central cluster that, while not exactly forming a figure, nonetheless suggests a human torso and head. Four feet tall, the canvas creates an inescapable bodily correspondence between the revolutionary Cubist figure being depicted and its observant viewer. Shifting Cubist planes of vibrant color set the figure in action.

Several depicted objects are more realist, which adds to the visual disjunction. One is the rifle, its narrow, steel-gray form enlarged and pushed into the visual foreground by a sharply delineated white shape, which cuts across the composition on a diagonal. Behind it is a wood-grained ammunition box, which slyly corresponds to Zapata’s body.

The landscape is another realist element. Behind the nominal figure is a ghostly volcanic mountain range like the one that encircles Mexico City and, over the figure’s shoulder on the right, what might be mesas or possibly chopped tree stumps. Two clumps of leafy green trees, one on each side of the torso, are placed like ornamental epaulets on a soldier’s uniform.

Bright blue sky across the lower half is matched by a sickly greenish veil above the mountains on top. Topsy-turvy colors signifying earth and sky together evoke a world turned upside down.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

The painting was produced early in a celebrated career that would expand for four decades. Yet it’s no wonder Rivera described it as “probably the most faithful expression of the Mexican mood that I have ever achieved.” Cubism isn’t known for expressing feeling, which makes Rivera’s work distinctive.

Needless to say, the landscape in “Zapatista Landscape” is of extreme importance. Agrarian reform was a crucial aim of the Mexican Revolution that was unfolding while Rivera was abroad. Territorial takeover in the Spanish conquest of Mexico had evolved over centuries into a system of vast private estates controlled by a small class of powerful landowners.

Nineteenth-century Mexican landscape painting sought to fuse national identity with the land, just like similar imagery in other North American and European art. Zapata’s peasant revolt in rural Morelos hinged on the refusal of the Mexican government to enact the agrarian reforms that had been demanded and, tentatively at least, promised. Rivera’s Cubist masterpiece, painted when he was just 29, brilliantly fuses the land, revolution and the peasantry — with Zapata as its modern emblem.

Sixteen years later, after the revolution and when he was again based in Mexico City as a leading artist of the Modernist era, Rivera painted the second addition to the LACMA exhibition.

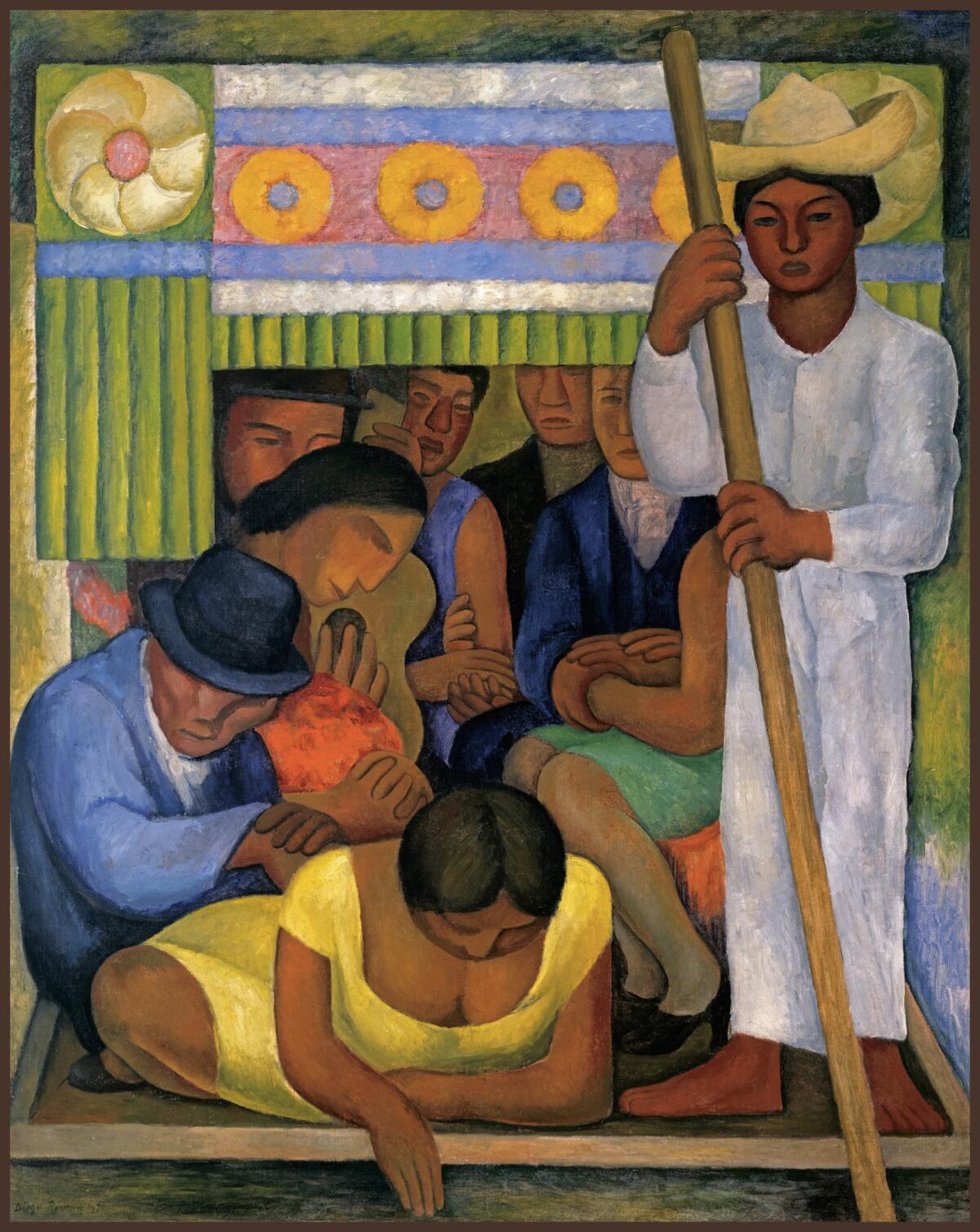

“The Flowered Canoe” shows more than half a dozen men and women on a Sunday outing in a pleasure boat on one of the famous canals in Xochimilco’s neighborhood. The life-size figure of a boatman on the right stands tall and straight, his cylindrical body, limbs and feet planted like a sturdy Aztec sculpture.

Indeed, the rigorously symmetrical composition is all cylinders, circles and squares, Cezanne’s modernity mixed with New World antiquity. An industrial machine style adapted from fashionable Art Deco design is applied to a casual urban pastime — “Domingo en el parque con Jorge.”

Rivera painted it specifically for his retrospective at New York’s then-new Museum of Modern Art. Only Matisse had been given a solo survey at MoMA before him. The picture’s lovely “Aztec Art Deco” patterning located Mexico’s enchanting present squarely between its proudly pre-Columbian past and its thoroughly modern future.

“Picasso & Rivera” remains at LACMA through May 7. The show then travels to the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

Jimmie Durham's art throws some well-aimed stones

Demian Bichir plays it cool in 'Zoot Suit'

How Latino theater born in the farm fields changed L.A. theater

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.