Review: Charles White show at LACMA pinpoints the power of an underappreciated black artist

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. on Spectrum News 1.

- Share via

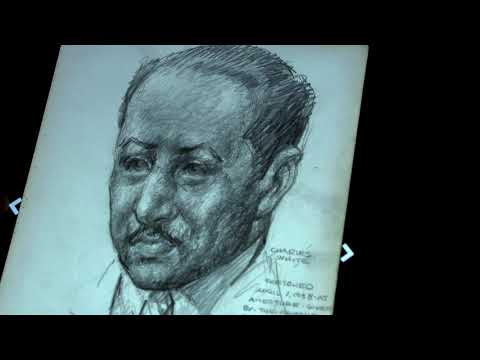

Charles White was a spectacular draftsman. His facility with graphite, charcoal, crayon and ink was evident from at least around the age of 17, when he drew an achingly refined self-portrait on a cardboard sheet.

That prodigious gift was both a blessing and a curse. A blessing because, when he died in 1979 — tragically young at barely 61, congestive heart failure perhaps a legacy of tuberculosis contracted during World War II — he left us a substantial body of powerful work that records and renovates a critical segment of 20th century American history.

And a curse because that profound aptitude ensured he would be out of step with powerful postwar artistic currents, which favored abstraction. He always had a core group of admirers — how could he not? — especially in the African American community, where segregation both de jure and de facto kept his work apart. But his exact talent was also devalued until he was gone.

Evidence is all over “Charles White: A Retrospective,” the formidable survey of about 100 works recently opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. A number of paintings are included, but the graphic work is what is almost uniformly commanding. Organized in association with LACMA by New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, institutions in the other two principal cities where the artist lived, the show is as timely as it is moving.

White was 47 in 1965 when, nearly a decade after arriving in Los Angeles and teaching at the old Otis Art Institute at MacArthur Park (now Otis College of Art and Design in Westchester), he drew “J’Accuse #1.” The work, more than 4 feet high and 3 feet wide, is richly rendered in mostly short, deliberate strokes of black charcoal and carbon-based crayon on off-white illustration board.

The drawing shows a veritable mountain of a woman. Seated, she is wrapped in a voluminous blanket, her large hands folded in her lap and her clear eyes staring straight ahead. As monumental in her bearing as the drawing is in size, anonymous and of African descent, she faces a viewer as an immovable force.

DESERT X: I drove 198 miles to see 19 artists’ work. Here’s the best »

The accusatory title is borrowed from the famous 1898 open letter by writer Emile Zola that publicly denounced the French establishment for covering up rank anti-Semitism permeating both the government and society at large. White’s drawing, absent Zola’s exclamation point and less threatening than simply a stated fact, does much the same: An American establishment that whitewashes the snarled structures of white privilege stands accused.

In the year the drawing was made, Malcolm X, subject of FBI wiretaps and surveillance, was assassinated. On a “Bloody Sunday” that March, Alabama state and local law enforcement armed with tear gas and clubs pulverized peaceful marchers at Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. Tensions escalated over the Voting Rights Act, which ended legally sanctioned state barriers to the franchise in all elections, building on the previous year’s Civil Rights Act outlawing discrimination in public accommodations.

Those tensions boiled over. Five days after the voting law’s passage, the Watts Rebellion reduced a swath of South Los Angeles to ashes, echoing conflagrations the year before in Philadelphia, Rochester, N.Y., and Harlem.

White’s drawing engulfs the figure in an atmospheric cloud of vertical striations, like falling rain. (He was a fan of prominent 19th century American painter George Inness, whose soft, moody landscapes he studied in abundant examples at his hometown Art Institute of Chicago.) She is at once humble yet grand. As much like one of the huddled masses that White portrayed during a stint making Social Realist murals for the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, she’s cloaked as a biblical saint, emperor or judge.

In this drawing, it is especially worth noting that she is a she.

The 1965 Moynihan Report — compiled privately for the U.S. Dept. of Labor and formally titled “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action” — had been leaking into the press. The controversial study claimed that the roots of black poverty lay in single-mother households.

Analysis by the powers that be indirectly (but inescapably) disdained White’s own full and impressive life — born to an unmarried domestic worker and a Pullman car porter of Native American (Cree) heritage and raised alone by her. As influential conservatives Rowland Evans and Robert Novak put it in a syndicated column published in this newspaper, even as the embers in Watts were still warm, “broken homes, illegitimacy and female-oriented home life were central to big-city Negro problems.”

“J’Accuse,” answers the bold and defiant drawing — No. 1 of 12 in a series on various themes that White would produce during the next year.

Indeed, women are perhaps his most frequent subject. Also that year, White made one of the retrospective’s showstoppers — “General Moses (Harriet Tubman).” In the 5-foot-8-inch-wide drawing, the intrepid leader of the Underground Railroad that surreptitiously shuttled escaped slaves to free states is shown seated on a primordial stack of massive boulders.

Feet planted, hands clasped, gaze steady, she’s as elemental and solid as a rock.

Thin horizontal spaces between the stacked stones behind her convert the formidable pile into something almost surreal — the suggestion of an all-seeing mask or a pair of whispering lips. The stones are as mysterious as any in a Caspar David Friedrich painting, at Neolithic Stonehenge or that form a carved Olmec head. Tubman becomes a universalized ancestral muse, communicating a determination for liberty across time and civilizations.

AT LACMA: Her name was Flora — lover of Alberto Giacometti and artist in her own right »

The exhibition is installed in a loose chronology according to White’s three home-base cities. Well-organized, it is nonetheless hampered in one unfortunate way: A blaring audio recording of portions of two White lectures plays on a loop, broadcast in the middle of one gallery but loud enough to interrupt viewing throughout the entire show.

The talks, given at LACMA in 1969 and 1971, include useful insights. But they’re a pedagogical intrusion; the tape should be transferred to headphones for private listening or simply shut off.

In Chicago, White learned the ropes, including painting in tempera on board. The fast-drying medium is as old as ancient Egypt, favored by many artists of the celebrated Harlem Renaissance, including Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence. He applied it to a Midwestern Regionalist style in which black lives mattered to a full representation of the American scene.

In New York, steeped in progressive leftist politics, he taught high school art classes in Harlem with his first wife, noted sculptor Elizabeth Catlett. (Divorced in 1947, he later married Frances Barrett.) White and Catlett shared two transformational journeys.

One was to the American South, where three uncles and two cousins had been lynched, and where he was brutally beaten for entering a segregated Louisiana restaurant. The other was to Mexico City, where he worked alongside Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Workshop). Rivera’s teeming masses especially informed White’s work.

“Mexico was a milestone,” he later said. “I saw artists working to create art for and about the people.”

Los Angeles is where his work matured, however, steadily shedding stylistic inspirations for straightforward realism, sometimes injecting a symbolic twist and developing its own distinctive resonance. The “J’Accuse” drawings demonstrate the transition — figures more direct and naturalistic, less stylized than in his earlier Social Realist imagery, and more authoritative because of it.

On occasion he could succumb to sentimentality. In one panel painting, a proud farmer with a pitchfork nods to rural fabulist Grant Wood.

More often, though, he transforms art historical subjects.

Card players occupy a conflicted social space, as they had from Old Master paintings to Cézanne. Conch shells, symbol of regeneration and awakening, turn up. A young boy plays cat’s cradle with a length of string subtly configured to evoke the innate perfection of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

Even the commanding “J’Accuse” and “General Moses” will put you in mind of Michelangelo’s powerful sybils lining the Sistine Chapel ceiling. White’s art might have run headlong into the juggernaut of abstraction, which regarded figure drawing as retrograde. But these are works that cannot be held down.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Charles White: A Retrospective’

Where: LACMA, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A.

When: Through June 9; closed Wednesdays

Info: (323) 857-6000, lacma.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.