‘Harald Szeemann’: A rare, fascinating exhibition about the curator, not the artist

- Share via

In 1969, a 34-year-old artist (and part-time rock band drummer) named Walter De Maria was one of 69 emerging American and European artists invited to participate in an unconventional museum show in Bern, the capital of Switzerland. The soon-to-be landmark exhibition carried the unwieldy title, “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form (Works — Concepts — Processes — Situations — Information).” De Maria suggested restaging a project he had recently tried out in Chicago.

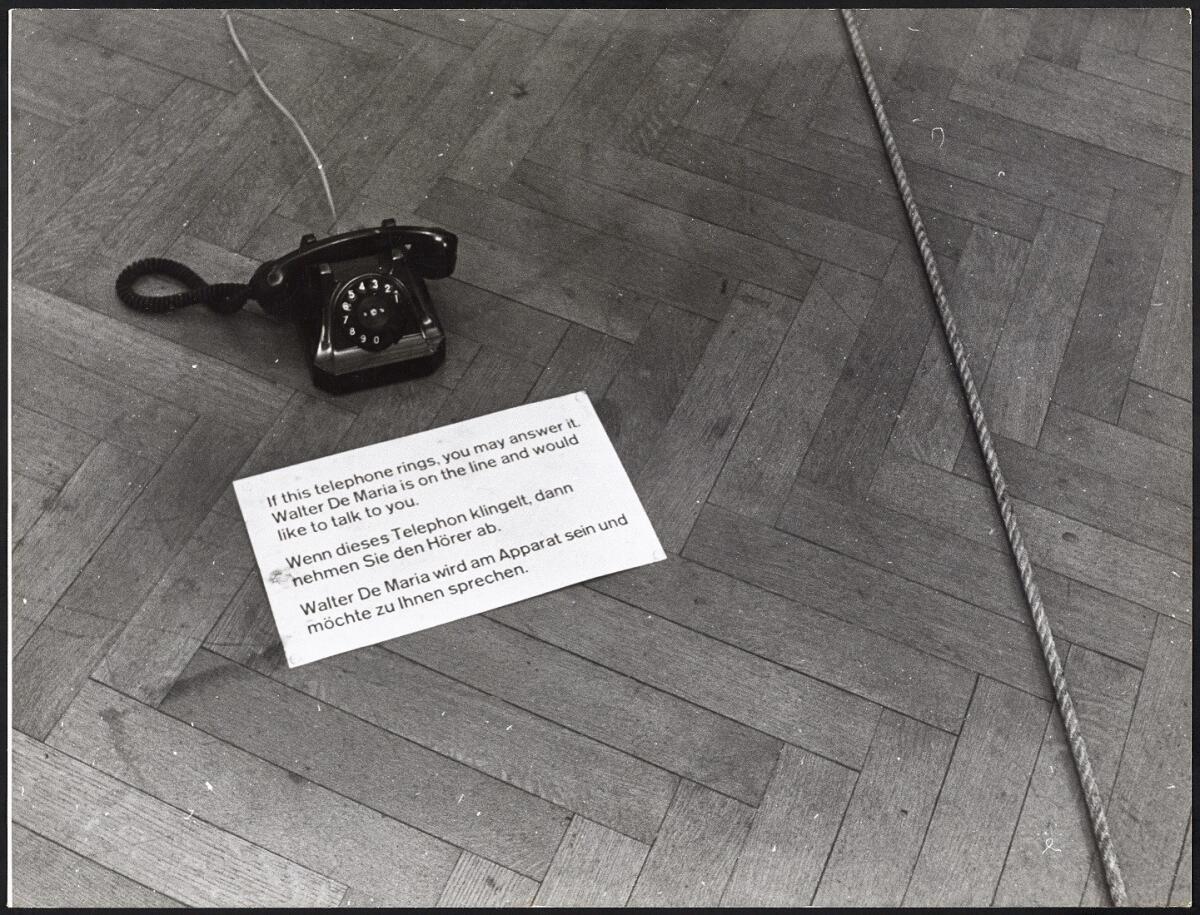

It consisted of an ordinary, rotary-style black telephone placed on the gallery’s parquet floor, as if it were a sculpture and the museum its pedestal. The phone was altered so that outgoing calls could not be made, while only the artist knew the phone number to call in. Next to it he placed a printed card.

“If this telephone rings,” the card said, “you may answer it. Walter De Maria is on the line and would like to talk to you.”

Just how many visitors to the Kunsthalle Bern spoke to the artist during the show’s run is unrecorded, so far as I know. A current exhibition at the Getty Research Institute in Brentwood, where documentation of DeMaria’s “Art by Telephone” is featured, is also unsure.

But there couldn’t have been many. In a neatly typed thank-you letter to Harald Szeemann, the show’s audacious curator, displayed in a Getty vitrine, the artist noted that he probably called the line no more than half a dozen times during the five-week run.

Sometimes those calls arrived in the dead of night, when the museum was closed, given the six-hour time difference between Switzerland and the artist’s New York studio. “I can imagine it ringing in the ‘palace at 4 a.m.’,” De Maria wrote, slyly invoking the title of a famous 1932 sculpture by Alberto Giacometti. That Surrealist dream-scape sculpture is a treasure in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

De Maria’s “Art by Telephone” is a textbook example of what Szeemann meant with his show’s own title, “Live in Your Head.” What mattered most was not a crafted physical object residing in an art museum, but the prospect of an actual connection between an interested audience and an artist’s way of thinking. The purpose was to upend the artistic certainties that museums inevitably imply.

And it wouldn’t be by way of some telepathic transmission, some sci-fi Vulcan mind-meld, either. The object was merely a catalyst for imagination. Stand in the gallery, look at the telephone on the floor and wonder, will he call? What’s he doing right now? Who is Walter De Maria anyway?

Where in the world is he? And if the artist calls, what would I say? Why is he doing this?

An audience would be asking questions about its immediate experience, like artists do. If a museum was a “palace” — a hallowed, historical space for the transmission of established power and value — an artist needed to find a way around it if questions were going to be asked rather than answers handed down. If he was successful, an audience would suddenly see things in a new way.

Metaphorically, a visitor would awaken in the palace at 4 a.m.

Szeemann, barely two years older than De Maria, had already been the director at Kunsthalle Bern for eight years, and he had grown dissatisfied with the museum status quo. The Getty exhibition discloses how he came to a new perspective — and how it was manifested in two of the most important shows of the last half-century.

After the landmark “When Attitudes Become Form,” Szeemann took on Documenta — a periodic survey of new art in Kassel, Germany. The 1972 Documenta 5, its poster featuring an illusionistic swarm of busy little ants drawn by Ed Ruscha, is widely regarded as the best of all the quinquennial shows, before or since.

The radical nature of these 50-year-old shows might be difficult to see today, when Postminimal and Conceptual art are firmly ensconced in the cultural pantheon. Szeemann’s pioneering curatorial technique is now routine — a measure of his influence.

Drawing on the massive archive of Szeemann’s papers that the GRI acquired in 2011 — the largest single archival collection it has obtained — Getty curator Glenn Phillips, independent curator Philipp Kaiser and their team have laid out a fascinating history. (The hefty catalog, a yeoman’s task to assemble given the volume of material from which to choose, is excellent.) It’s a proper swan song for outgoing GRI director Thomas W. Gaehtgens, who initiated the acquisition and who retires in the spring.

“Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions” is a rarity — a show about a curator, not an artist. Occasionally it slips into hagiography, not quite acknowledging the degree to which Szeemann happened to be in the right place at the right time. But Szeemann was the right person to be there, then — director of an establishment institution but who didn’t think like an administrator or bureaucrat. He wasn’t an organization man.

The world in 1968-69 was in turmoil, a seismic social and political ruckus spanning civil rights clashes in Alabama, student revolts in Paris, the Russian invasion of Prague, the Tet offensive in Vietnam, civil war in Biafra and more. The hair-raising mayhem hardly escaped art and artists.

Perhaps it is more accurate to say that the show is about a curator as artist. Much like Oscar Wilde, who conceived of the critic as artist at the transformative end of the 19th century, Szeemann formed a distinctive aesthetic philosophy about artists who were his contemporaries. His exhibitions expressed a shared philosophy.

“The major characteristic of today’s art is no longer the articulation of space but human activity,” Szeemann wrote in the catalog to his show at the Kunsthalle Bern — a catalog, not so incidentally, that is more like a collection of loose artist-files held together by a metal fastener than a traditional book. “The activity of the artist has become the dominant theme and content.”

Selecting mostly emerging artists in his own age group and working in Europe, New York and Los Angeles, he let them loose in his museum.

Robert Morris assembled piles of combustible materials, which he incinerated at show’s end. Michael Heizer smashed up the pavement in front of the museum with a wrecking ball. Robert Barry photographed the roof of the building, where he had distributed mildly radioactive material. Robert Smithson photographed mirrors on the roof, displacing art history’s shelter with topsy-turvy reflections of trees and sky.

In the galleries, Gilberto Zorio suspended torches that periodically burst into flame and consumed themselves. (He was lucky the building didn’t ignite.) Lawrence Weiner chiseled white plaster off a wall in the shape of a square to expose the implacable institutional structure beneath — in the process reversing Kazimir Malevich’s 1918 “White on White,” an ethereal white square painted on a gauzy white background and a benchmark of spiritual abstract painting.

Almost half of the artists were American, including several from Los Angeles (Edward Kienholz, Bruce Nauman, Allen Ruppersberg) and others who would soon be working in the city (Douglas Huebler, William Wegman). A page from the curator’s notebook lists nearly 30 people Szeemann visited during a Southern California trip, including Ruscha and Robert Irwin, as well as gallerists Eugenia Butler and Esther Robles.

Szeemann’s international show recognized that the world, including the art world, was shrinking. While the curator was assembling it, the first astronauts to orbit the moon took flight — the first humans to visually observe the Earth as one unified sphere. The first airline jumbo-jet took off just six weeks before the show opened, launching mass trans-Atlantic and trans-continental travel.

One of the show’s great failings, however common for its day, was that 66 of the 69 artists were male (almost exclusively white). Systems artist Hanne Darboven, Postminimalist Eva Hesse and filmmaker Jo Ann Kaplan were the only women to make the cut in an otherwise socially attuned exhibition apparently indifferent to the feminist movement.

The Getty show has some surprises. I had forgotten, for example, that an American corporation sponsored it.

Tobacco giant Philip Morris was beginning a push into European markets — the Marlboro Man, its cartoonish cowboy, soon captured them — and its stated claim of valuing corporate creativity was being branded with the newly popular world of contemporary art museums. The company gave Szeemann a hefty $150,000 budget, a sum equivalent to more than $1 million today, to mount his path-breaking show.

In a marvelous (and unrealized) proposal for an exhibition poster, a witty contour drawing by Swiss artist Markus Raetz shows a Philip Morris cigarette pack on top and an ashtray with Claes Oldenburg-style crushed cigarette butts on the bottom. The pristine pack is captioned “When attitudes …,” while the butt-filled ashtray is captioned, “… became form.” Desire ends in ruin and decay.

The Getty show is divided into three sections. The first, focused on the momentous Bern and Kassel shows, is the most absorbing.

Then comes “Utopias and Visionaries,” a loose-limbed survey of three 1970s and ’80s exhibitions in which alternative political movements, outsider artists and mystical philosophies were injected into standard histories of Modern art. Finally, “Geographies” is a grab bag of later shows (Szeemann organized around 150 in his career), including one on machine imagery and another on “Swiss identity,” a fraught concept in a region where German, French and Italian histories collide.

Off site at the downtown Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, a satellite show re-creates a revealing 1974 Szeemann project. He had resigned as Bern’s director not long after that controversial exhibition closed and, unemployed after Documenta, he decided to turn an apartment above Bern’s Café du Commerce into a museum for a show about his recently deceased grandfather, Étienne Szeemann.

Beauty was Étienne’s business: A Hungarian-born hairdresser, who lived to 98, he had invented a permanent wave machine. The gizmo of tubes, coils and wiring looks like something from Dr. Frankenstein’s lab, useful for glamorizing the monster’s bride.

Étienne’s grandson, a hoarder who saved virtually everything even vaguely meaningful to him throughout his life, sorted, cataloged and displayed what his beloved grandfather left behind. The ICA LA has reconstructed the small apartment as a freestanding gallery installation.

Its hallways and rooms are filled with neatly organized photographs, papers and artifacts — grandfather’s family tree, roots in the Austro-Hungarian empire, professional life, hobbies and daily activities. Amusing reminiscences from family include the curator’s sister: “I liked grandfather, but I don’t have any illusions. You are just as egotistical as him.”

Nothing in “Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us” is especially captivating, not the wigs and combs nor the postcards, engraved diplomas and knickknacks. What makes it worth seeing is its example.

Perhaps the most intensely personal of Szeemann’s shows, it speaks to meticulous, exhaustive obsession. A scrupulously organized archive of a life lived, it mirrors what the Getty has likewise undertaken with the celebrated curator.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions

Where: Getty Research Institute, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Through May 6; closed Mondays

Information: (310) 440-7300, ww.getty.edu

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us’

Where: ICA/LA, 1717 E. 7th St., L.A.

When: Through April 22; closed Mondays and Tuesdays

Information: (213) 928-0833, ww.theicala.org

UPDATES:

For the Record

3:40 p.m. This article was updated to correct a reference to Glenn Phillips. He is a Getty curator, not a Getty consulting curator.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.