Review: Paul Robeson’s roots examined in ‘Tallest Tree in the Forest’

- Share via

Multi-hyphenated celebrities are all the rage these days, but none can match the gravitas of Paul Robeson.

Singer, classical actor and civil rights activist, Robeson (1898-1976) had given up a career in law to pursue the stage after distinguishing himself as a scholar and an athlete. There was no discipline, it seemed, that he could not conquer.

Fame provided a platform for him to speak out against oppression in America, and that is where the plot shifts in the glorious biographical narrative of an overachieving son of a minister father who had been born a slave. Robeson’s prodigious and pioneering acclaim gets tangled in Red-baiting controversy.

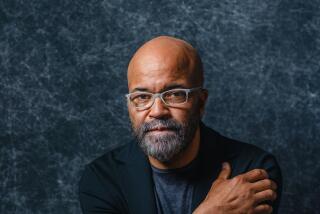

Daniel Beaty brings this story to the Mark Taper Forum in his solo show “The Tallest Tree in the Forest,” a respectful and intelligent if dramatically disappointing recap of Robeson’s life. Beaty, a writer, singer and performer whose program bio informs us is also a “highly requested key note speaker and thought leader,” has clearly been inspired by Robeson’s path-breaking career, and his show seems built to introduce his hero to a new generation of audiences.

PHOTOS: Faces to watch 2014 | Theater

The production, directed by Moisés Kaufman on a set by Derek McLane that makes gorgeous use of the Taper’s exposed backstage area, is impeccably laid out. The writing and acting may have the earnest quality of an educational theater offering, but the design (which includes David Lander’s majestic lighting) is top notch.

There’s clearly been a lot of love lavished on a work that sets out to honor an important figure in African American history. I wish I could say that it had a more profound artistic impact or that it gave us a stronger sense of Robeson’s theatrical gifts. Beaty is a trustworthy guide, an agreeable performer and a capable singer. Robeson’s vocal command, however, is a bit of a stretch for him. This impersonation can’t conceal its artificiality.

To begin, Beaty’s Robeson offers a rendition of “Ol’ Man River” from “Show Boat,” the song Robeson made famous despite the qualms he had about some of the lyrics. (This wrestling with his conscience would haunt him throughout his career.) The number by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II handsomely repaid him by making him a star.

“I became the most well-known black person in the world,” Robeson tells us. “The tallest tree in the forest they called me. My height’s enabled me to see what most cannot. My branches have stretched continents. I’ve weathered many storms.”

This pulpit tone pervades Beaty’s piece, which proceeds to review (with the sanctioned amount of poetic license) watershed moments in Robeson’s life. The various chapters in this condensed biography are interspersed with musical numbers, arranged by music director and conductor Kenny J. Seymour.

INTERACTIVE: Hollywood’s Theatre Row

Beaty plays all the characters in a manner that aspires to differentiate the various roles as vividly as possible. His mimicry of 10-year-old Paul learning from his brother the necessity of fighting back or his imitation of “Essie,” the brilliant, driven woman who would become his wife and manager, are marked by cutesiness, but they get the narrative job done.

Robeson’s string of successes, on the musical stage and in O’Neill and Shakespeare, gives him an international spotlight. His disappointment with the demeaning depiction of tribal customs in the film “Sanders of the River,” in which he starred, develops a keen interest in Africa and the plight of African people everywhere. A trip to Moscow inspires a long affinity with the Soviet Union, which leads to all kinds of trouble when FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover deems Robeson a national threat.

Beaty frames Robeson’s political journey with a good deal of complexity. Robeson is in search of justice, racial as well as economic, and it is in joining these two causes that he disturbed so many in power. Eventually he was brought before the House Un-American Activities Committee, where his resounding voice found ample reason to boom.

The treatment here comes close to hagiography, but Robeson’s personal flaws (his marital infidelities, his stubborn refusal to renounce certain ardently held views even after new information has come to light) aren’t covered up. He’s a saint with the flaws of an ordinary sinner.

“The Tallest Tree in the Forest” is one of two prominent theatrical offerings on Robeson in L.A. at the moment. (The other is the Ebony Repertory Theatre revival of Phillip Hayes Dean’s “Paul Robeson” at the Nate Holden Performing Arts Center, starring Keith David.) Robeson deserves the attention. “The Tallest Tree in the Forest,” for all its shortcomings as theater, serves a venerable educational mission.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.