For Japanese Americans, ‘The Terror’ is personal

- Share via

VANCOUVER, Canada — George Takei sat in his trailer on the set of “The Terror” dressed in his character’s charcoal-blue yukata as we traded histories in bittersweet shorthand. For those whose families were among the 120,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II, one need only say the names of places to paint a picture.

“We went from Rohwer to Tule Lake,” said Takei, 82, who was a child when he and his family were imprisoned in concentration camps by the American government in 1942, more than two decades before he blazed a trail for Asians in Hollywood as “Star Trek” icon Hikaru Sulu. “There were no charges, no trial. We were rounded up.” (Takei will join the Los Angeles Times Book Club on Sept. 10 to discuss his graphic novel about the experience, “They Called Us Enemy.”)

I know those names and others like them. They are etched in menace and melancholy in my mind. Topaz. Jerome. Heart Mountain. Tule Lake, where more than 18,000 were incarcerated during the war, was also a stop on the worst journey of my family’s lives.

I told Takei the places in my family’s history and he nodded. For years, younger Japanese Americans have been telling him where their relatives were sent, seeking to understand the burdens their loved ones carried.

He’s always shocked they don’t know more. The Japanese have a word for what got the older generations through the war: Gaman. Persevere. Internment wasn’t something that was talked about.

Starting Aug. 12, Season 2 of AMC’s anthology “The Terror” — set within a WWII-era Japanese American community plagued by horrors supernatural and human — will bring new attention to this underexamined chapter in American history.

“It’s sad and unfortunate, but also not surprising, that this country’s not very proud of [internment],” showrunner Alex Woo said of the 10-episode season, titled “Infamy,” which marks the most significant on-screen attempt to account for and exorcise the demons of that past.

“In both [seasons], we’re using a horror vocabulary to put you in the skin of the people who experienced this historical event,” said Woo, who co-created the season with Max Borenstein. “You will feel the fear they feel. You will feel the terror they feel.”

The timing could not be more apt.

On this early May day, we are still months away from the protests at Ft. Sill, Okla., where Japanese American internment survivors decried the site’s reuse as housing for migrant children from the southern border. We have yet to endure the hate-fueled mass shootings in Gilroy and El Paso. And yet America’s family separation crisis has deepened since filming began in January, and U.S. policies and rhetoric targeting non-white and foreign-born people already alarmingly extend the nation’s racist history.

With the Trump administration planning to move 1,400 migrant children to this fortified Army post later this summer, a small group of Japanese American World War II internment camp survivors came to the gates Saturday to make their opposition known.

Takei feels the series’ urgency. He felt it a few years ago before the 2016 election, when he took his internment play “Allegiance” to Broadway.

“We were a threat to national security because of the way we looked,” Takei said of the racist hysteria that led to President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, authorizing Japanese American incarceration. “We were potential spies, saboteurs, fifth columnists. That sweeping statement, again, I heard as a senior citizen on Broadway — being mouthed by Donald Trump.”

“It’s an American story that all Americans should know about, just like slavery, or what happened to the Native Americans,” Takei added. “And yet our history books have been very mute on the subject.”

Set in a vibrant Japanese American fishing village on Terminal Island near San Pedro, “The Terror” follows a group of Japanese immigrants and their U.S.-born children as a yurei, or spirit, haunts them in the days before Pearl Harbor through the end of the war.

Takei plays retired fishing captain Yamato-san, who is arrested with other community leaders and taken to a freezing prison camp in North Dakota.

Before he left to film a scene set during obon, a festivity honoring the ancestors, I showed Takei a photograph of another Yamato — my grandfather, whom authorities took from Tule Lake in the dead of night after he dissented against the controversial questionnaire that demanded military service and loyalty from internees. The rift the questionnaire caused was the crux of “Allegiance,” and will be portrayed in “Infamy.”

Takei asked with great interest if my grandfather was still around. He’s not, I answered. “Oh,” he nodded quietly, with a bittersweet smile. “They’re all gone.”

I was a child when I first heard about the camps, via fragmented, painful memories seldom spoken aloud. When they were shared, it was in a matter-of-fact tone that shielded us from the full brunt of the trauma.

My grandmother described the day in 1942 when she and my grandfather arrived with my infant mother and what possessions they could carry to the Tanforan “assembly center,” one of several racetracks that housed Japanese Americans along the West Coast — where the whitewashing was so hastily painted on, the smell of manure oozed from the walls if you poked them.

Today, the racetrack is a shopping mall, but most people don’t know its history: Human beings in a horse stable. Eventually, both sides of my family were sent to a series of inland camps, where they’d spend the next three years incarcerated. It’s no wonder that, even long after the war, the details were difficult to relive.

I met background performer Pat Rose sitting in a tent filled with extras in midcentury western clothes, traditional Japanese kimono and period hair.

The third-generation Japanese Canadian described filming a large arrival scene at the Hastings Park racetrack at Vancouver’s Pacific National Exhibition. Now a popular amusement complex, during the war, Canadians of Japanese descent were interned at the site.

Rose’s relatives arrived there decades ago. She thought of them the whole time. “My grandfather owned a saw mill, and he owned a house and a car, and everything was taken away,” she said. “He told the family, ‘This is probably only going to be two or three months. Don’t worry. We’re coming back.’”

“I had tears in my eyes when I was going through the scene,” she added. “I never thought I would experience something like this.”

Because “Infamy” was intentionally cast with actors of Japanese heritage, personal ties weave through the series. Several of the season’s directors, writers and crew members are also of Japanese descent, including Josef Kubota Wladyka, who directed the first two episodes.

Derek Mio stars as Chester Nakayama, a second-generation Nisei and aspiring photographer navigating racism, generational conflict and the appearance of a mysterious woman named Yuko (Kiki Sukezane). Meanwhile, elders begin to suspect an evil bakemono has followed them to America from the old country.

Chester’s father, Henry (Shingo Usami), has his own harrowing arc, drawn from experiences of first-generation Japanese immigrants, or Issei. It’s Chester’s mother Asako, though, played by Naoko Mori, whose face haunts me: As the Nakayamas report to their assembly center, they learn that America sees them not just as the enemy, but as less than human.

Cristina Rodlo plays Luz, a Mexican American student and Chester’s girlfriend, who chooses to join him in the camps. Their cross-cultural relationship further underscores the season’s relevance, she said. “It’s the right moment to tell the story, with everything that’s happening in the world — especially in the U.S. We have to see how much we’re repeating the same thing over and over again.”

Masako Miki came to this picturesque landscape of snow-tipped mountains and desert shrubs Saturday on a mission of remembrance.

My father was born in Oakland and deemed an enemy alien at the age of 1. He can recall little of his time behind barbed wire, but remembers dust storms so blinding that as a toddler he’d get lost finding his way back to his barracks. He can still taste the dirt and grit that burned his throat and crusted his eyes. He remembers the panic. He remembers how hard it was, years later, to talk to his parents about what they’d all lost.

I thought of my parents and grandparents and their friends, the last generation to live through internment, as I arrived at the fictional Colinas de Oro War Relocation Center, where much of “Infamy” takes place.

Birds circled in the sky above a line of tall pines. A sign warned, “STOP ... SENTRY ON DUTY” to people of Japanese ancestry. Wooden guard towers loomed as I stepped past the barbed wire and into the past.

I could see why walking onto the set was overpowering for Takei.

The acting wasn’t acting.

— George Takei

“It is very, very real,” he told me. “The texture of the strips of wood that held the tar paper intact, the crawl space underneath the barrack. Our dog used to crawl under there. All those memories came back. The acting wasn’t acting.”

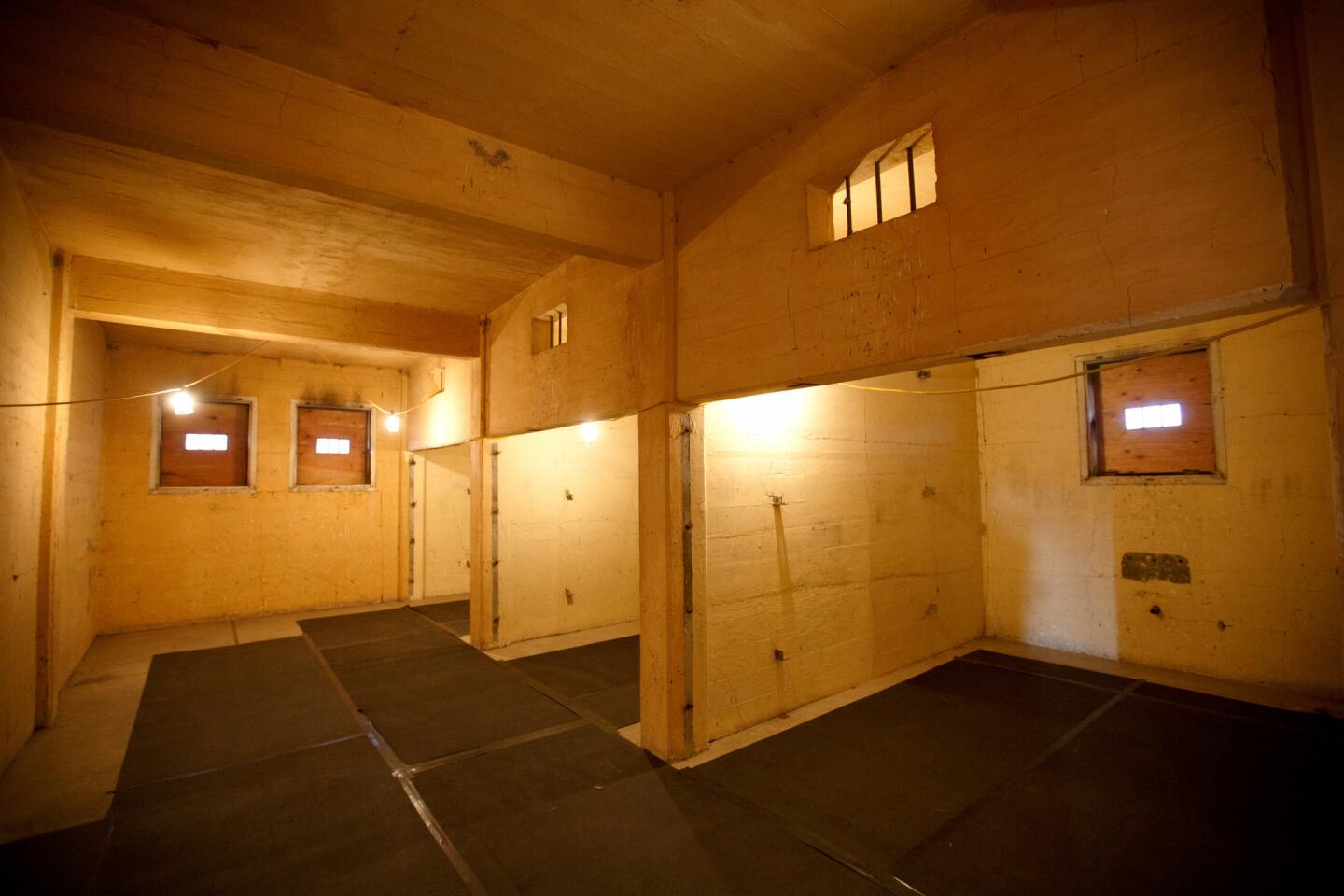

A fraction of the size of actual internment sites, Colinas de Oro was modeled after the Manzanar camp in Central California, said production designer Jonathan McKinstry, who also created the unforgiving Arctic setting of “The Terror” Season 1. After walking past a makeshift garden and an American flag gently rippling in the wind, I entered one of the barracks, still set-dressed with sparse cots and bedsheets hung for privacy.

I’d only ever seen internment in black-and-white images. Here it came to life in unsettling color. Wandering past potted bonsai and handmade chimes hung from posts, I wondered what comforts my grandparents had to make their prison feel more like home.

Communal latrines without doors. Multiple families crammed into a tiny wooden shack. Armed guards in high towers, their guns pointed inward. Freedom on the other side of the barbed wire.

“I think horror puts you in the skin of the person experiencing the terror,” said Woo, whose team pored over historical accounts, photographs and testimonies. “Hopefully the viewer will feel and be able to empathize with the terror of the historical experience.”

Mio wore a heavy jacket over his period coat and slacks, as he perched in a tall folding chair in the grass while crew members prepped a farmhouse set for filming. Waiting to film a scene opposite Rodlo, Mio told me of his family ties — not only to internment, but to the character he plays.

“This is a very special project for me personally,” he said with a sharp intake of breath. “Because my family is from Terminal Island.”

Mio’s great-grandfather immigrated to the coastal Japanese American enclave as a boy, barely speaking English. Eventually he opened his own cafe on Terminal Island, a cannery town dubbed Fish Harbor, and sent for a bride from his hometown of Wakayama, Japan, where many residents had roots.

Then war broke out, and Terminal Islanders were given 48 hours to leave. Mio’s family lost everything and were sent to Manzanar. When residents returned after the war, their homes and businesses had been razed. There was nothing left.

“Infamy” depicts the night when, at the start of the war, authorities raided Terminal Island and arrested its community leaders. “That actually happened to my family,” said Mio. “My great-grandfather was one of the first to get rounded up.”

Mio studied interviews recorded by original Terminal Islanders, including those of his own relatives. “In researching for this, it became more of a family research project,” he said. “I got to reconnect with my grandfather, who has since passed, and my great-grandparents who have passed.”

“Hearing their firsthand accounts of when they first came in the middle of the night and hauled my great-grandfather away — my grandfather was pleading with them and crying, ‘No, take me instead ...’” Mio trailed off, blinking away tears. “We shot that, and it was very emotional.”

In another minute, he’d be called on to finish filming Chester’s journey. But as crew members bustled about, we sat there quietly, thinking of our families, their stories, the names of the places that marked their lives. A gentle wind rolled in across a neighboring field, and for a moment our loved ones sat beside us.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.