Column: Americans have forgotten how to behave. And it’s time to stop blaming the pandemic

- Share via

It started as an airborne virus.

At the end of 2020, after COVID-19 shutdowns ended and restrictions loosened, many people began flying again and, in far too many cases, behaving badly while doing so. So badly that the Federal Aviation Administration was, for the first time, forced to keep track of the number of unruly passengers — many of whom were pushing back against masking requirements — and issue a zero-tolerance policy. Rude and angry passengers began to be booted off flights.

The situation only got worse, even after masks were no longer required. Adult tantrums, rule-breaking, rudeness and general bratty behavior has not only become increasingly common on airplanes, it has spread. To concerts, movie theaters, restaurants and even the Happiest Places on Earth, Disney resorts.

To be sure, most people continue to behave as reasonable human beings who understand the basic expectations of communal behavior. But a growing number of people apparently do not.

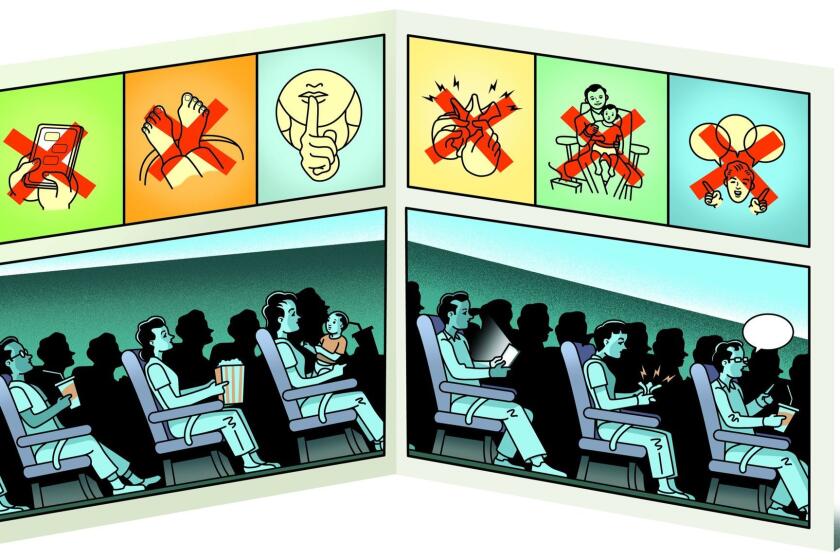

Cellphone use and loud conversations in movie theaters, long the bane of cinephiles, have become the norm, with audience members regularly talking, singing, thumbing through their illuminated social media accounts, taking photos or blatantly making TikTok videos.

Where once music fans might have tossed flowers, glitter and the occasional piece of underwear onstage, some now heave very substantial things directly at performers. Pink, Harry Styles, Bebe Rexha and Cardi B have been struck onstage by items thrown by audience members. In Pink’s case, it was a wheel of Brie. In Bebe Rexha’s, a cellphone, which hit her in the face and left a wound that required stitches.

Since restaurants reopened their dining areas, food servers around the country have complained of increased rudeness, including by the likes of James Corden, while restaurants remain chronically understaffed and struggling to fill positions. (Wonder why.)

Last year, faced with increased incidents of brawling among park guests, Disney resorts in California and Florida added admonishments about courtesy in the “What to Expect” portion of the resorts’ websites.

Corden is saying goodbye to his CBS late night show with a starry slate of guests and a primetime special Thursday, but he leaves behind a lopsided legacy.

Despite a spate of “Why is everyone so mad?” essays and “Check yourself” conversations on social and legacy media, it doesn’t seem to be getting any better. As celebratory as the “Barbenheimer” weekends have been, screenings of both films have seen their share of physical altercations as well as arguments over the “right” some people believe they have to use their phones to take photos and videos and distract themselves during any “boring” parts.

It would be easy to blame COVID-19 — to say, as many have, that during the pandemic we simply forgot how to be with other people. And the pandemic, which halted and then reset so many things, is a big factor. It is difficult to transition from seeing anyone outside your bubble as a potential source of deadly infection to contentedly rubbing shoulders with them at Disneyland.

Children and teens were hit especially hard by shutdowns and other forms of social distancing that occurred just as they were learning or practicing key social skills. Declining mental health among teenagers and increased disciplinary problems in schools may well have roots in the loss, fear, political divides and social disruptions of the pandemic. All of these can lead to unruly or violent behavior, and not just among young people.

Our growing tendency to act as if the pandemic is over — something that simply happened, past tense, and left no lasting scars — is certainly not helpful to our collective mental or physical health, and the perilous political divides over masking and social distancing continue to create tensions between those who still take safety measures and those who, for reasons known only to themselves, see a mask or a refusal to be in a crowd as a personal affront.

But even more than the difficulties of dealing with other people, who have always been (to quote Jerry Seinfeld) the worst, the habits we picked up while burrowed in at home have exacerbated the situation. The main one being the belief that we control everything all the time.

Or, in TikTok parlance, that we are always the main character.

No reason to be polite to servers if you’re ordering from Postmates; no chance to chat with Amazon delivery staff who are not able to stay long enough in any one place to do so; no need to resist the temptation to look at your phone or talk while watching a movie at home.

Although bad personal habits play a big part in the current invasion of the full-grown toddler, they are not the only factor. At home, you might have to wait in a line for the bathroom but you won’t have to watch those who can afford to pay for Platinum status or Express line tickets swanning past you — or sit on the tarmac for three inexplicable hours.

On Wednesday, Drake became the latest artist to get hit by an object hurled by a fan at a concert. Should we blame the pandemic? Social media? Lazy bouncers?

In airports and on planes, outrageous behavior may have started with disagreements over masks, but it has continued in part because flying has become alarmingly expensive and increasingly awful.

If you have paid what pre-pandemic would have been business-class prices for an economy seat, you probably expect, at the very least, that your flight will actually take off, and in a timely fashion, and once finally in the air the air conditioning and in-flight entertainment screen will work. Too often those expectations are thwarted by airlines that seem to prefer having inevitably angry consumers to dealing with the problems in a meaningful way.

Unfortunately, instead of learning from airlines, other businesses appear to be embracing their ways, with similar effects.

Concertgoers paying hundreds or thousands of dollars for a ticket may well expect to clearly see and perhaps even interact in some way with the performer. When it costs $20 for a movie ticket and another $20 for concessions — that’s per person, mind you — it’s not a stretch to expect two hours of wildly engrossing entertainment. If the film is not providing it, then your phone or conversation with your companions just might.

Not reasonable, perhaps, but theoretically understandable. The escalating price of just about everything implies an increase in value that, in most cases, is not delivered. So some folks simply create their own perks — giving vent to rage or breaking traditional rules of social conduct (i.e., doing whatever the hell they want.)

If you feel you are paying VIP prices, you may well expect to be treated like a VIP.

Also, and this is a general thought for all service industries: If your business is chronically short-staffed, you are pretty much guaranteed unhappy customers, some of whom will, inevitably, behave badly. Try offering higher wages and better benefits to achieve full staffing; people will pay for good service and convenience, but only if they exist.

As is so often the case with any signs of cultural degradation, social media also must shoulder some of the blame for our regression. With the world in all its glory and vice dinging away in our pockets, it is difficult not to check in continually, no matter where we are or who surrounds us.

Not long ago, I went to see “Get Out” at my local Long Beach multiplex.

Many of us are determined to use our phones’ vast powers to achieve fame and fortune. Dangled for years as the ultimate get-rich-quick scheme, the viral video is our culture’s Holy Grail; the displeasure of fellow “Oppenheimer” viewers or concertgoers who don’t want their experience interrupted by your posing or shoving your way to a better view is simply an acceptable risk.

Who cares about the 36 people who would also like to use that super aesthetic bathroom with the great lighting? Their anger is a small price to pay in the quest for lucrative sponsorship.

Social media can be, and has been, used to capture all sorts of truly terrible behavior, including police racism and brutality, that might otherwise go unreported or unpunished. It also can turn someone who is just having a very bad day at the grocery store into the day’s poster child for privilege, or make it seem like every flight/theater/concert/sporting event is plagued by awful people doing awful things.

If I knew how to control the latter without curtailing the former, I would be at this moment flying first class somewhere amazing and feeling irritated that they have run out of beef dinners.

So where do we go from here? If the possibility of having your bad behavior captured and shared on social media is not incentive enough, I am on record as being a big fan of PSAs. They helped us use seatbelts, quit smoking and stop littering; they could help us regain our social mores. New York City had some success with subway ads asking riders to offer their seats to the aged, pregnant and disabled and to stop with the man-spreading. Why not try plastering a few billboards and bus stops with a reminder not to act like a monster when you leave the house?

Or everyone could just hire, at fair wages and decent benefits, a bunch of empty-nest moms who know how to keep people in line (when they’re not going off the rails themselves).

As my own mother would say, the world is not our living room, and sometimes good social behavior comes down to not making a bad situation worse.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.