Learning to be a conductor is exorbitantly pricey. A new L.A. co-op offers a corrective

- Share via

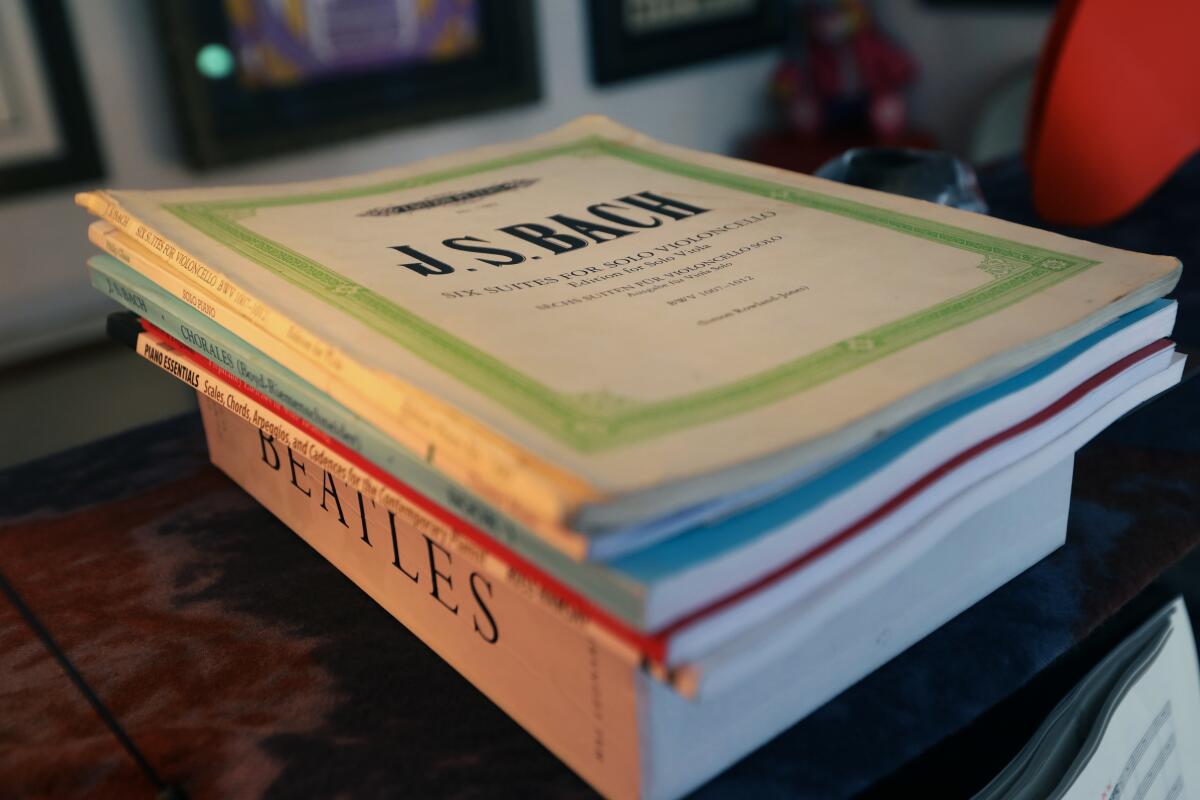

At the end of a cul-de-sac in Beachwood Canyon, a group of musicians meets in a garage. Decked out with a couch, rugs, mood lighting, sound equipment and an upright piano, this garage is designed for making noise.

But on this particular evening — silence. Welcome to the Hollywood Hills’ quietest garage band session and the inaugural meeting of the Los Angeles Conducting Co-op, where instruments lie dormant on some nights, and the music is all in your head.

The Los Angeles Conducting Co-op is a new organization founded by violinist and producer Lisa Liu, conductor Christopher Rountree and violist, curator and broadcaster Nadia Sirota. Their mission is straightforward: “Pool resources to defray the costs of studying symphonic conducting.”

The group met for the first time in June of last year. Sirota donated the space — that garage/rehearsal/studio/hangout spot, affectionately known as “the rumpus room,” is hers. Rountree volunteered his time as the workshop’s coach. And Sirota, Liu and the other handful of co-op participants paid $500 each to study the art of conducting in a supportive environment and practice conducting in front of an ensemble of their peers.

On night one, they focused on technique, digging into the minutiae of score analysis, complex rhythms, subtle arm and hand gestures, even facial expressions and posture. They stabbed blank white sheets of paper with their batons, then rehearsed flicking their wrists with a staccato motion that sent the pierced pieces of paper flying off the tips of their sticks.

They also sat together in a circle and conducted an imaginary orchestra in unison and silence, hearing the music simultaneously in their minds as they followed their identical scores. “Like some crazy ESP s—,” Sirota says.

Like instrumentalists, conductors need to hone their skills through regular practice. To some extent, they can do that on their own, studying a score meticulously until they hear each part in their head exactly as they want it to sound, then rehearsing the gestures they’ll use to draw that desired sound from an orchestra.

“You can get to this confident place in silence because you’ve summoned this ethereal nonexistent thing,” Sirota says. “And then musicians get there, and the thing you hear so loudly in your head is not exactly what’s happening in real life.”

Conducting students at conservatories and large music schools have access to orchestras because their peers provide cheap or unpaid labor as members of student ensembles. But outside of educational institutions, musicians rightly expect to be paid for their skills and time, so hiring an orchestra is massively expensive.

“That puts up a huge barrier in terms of what kind of people become conductors,” Sirota says. “It requires a significant outlay of money, and we were trying to figure out how to create opportunities that just didn’t cost so much.”

Sirota and her fellow co-op members are all accomplished professional musicians — members of elite orchestras, sought-after contract players, a film composer — who spent their conservatory years honing their skills on their instruments. Now, they want to expand their skill set to include conducting without spending many thousands of dollars on private tutors or returning to school.

Conductor training “happens in a swirl of insane privilege,” Sirota says. “Just to have the opportunity to study music on this level and not get paid for a really long time. ... It’s a privilege to learn how to do this thing.”

Liu and Sirota both sought out conducting lessons during the pandemic. Liu had a residency coming up that required some conducting, so she started taking private lessons with Jonathan Merrill, who teaches orchestral conducting in the UCLA Extension film scoring program. Sirota reached out to Rountree, her friend and the founder, conductor and creative director of the innovative chamber group Wild Up.

Sporadically throughout 2020, Sirota and Rountree met informally at Griffith Park, masking up, sitting on blankets 6 feet apart and conducting their way through repertoire. “We were out there waving our arms and getting deep into the score,” Rountree says. “And then somebody would miss the bassoon entrance, but of course, there is no bassoon.”

Liu and Sirota both wanted time in front of an orchestra to test out the techniques they were picking up in their private lessons in front of real musicians instead of imagined ones. They hatched a plan; maybe they could find some friends to join them and be each other’s orchestra.

Through social media, they rounded up a diverse group of friends and colleagues who also wanted to try their hand at conducting. After that first night of quiet practice, they met again to make some noise, taking turns conducting, then playing in the small orchestra when someone else had the baton.

In the true spirit of a co-op, all of the participants’ workshop fees went to paying the orchestra musicians, primarily themselves, in addition to a few extra folks who joined in to fill out the ranks. After members were paid for their time playing in the group’s orchestra, the real cost of the workshop was just $250.

“We’re trying to keep the prices as low as possible,” Sirota says. “It’s like a one-to-one exchange, just paying musicians. That’s basically where our entire budget goes.”

Sirota, who recently turned 40, has been interested in pursuing conducting since high school. “But our generation came up in this old-school classical music mode where to be a female conductor is an incredible flex. I felt how much of a flex that would be and was like, ‘You know what? I’m going to play viola because I know I can succeed in that,’” she says.

For centuries, white male conductors have, quite literally, been put on pedestals in the orchestral world. Their job seemed elusive because it was for so many women and people of color who were systemically barred or discouraged from learning this elegant and rewarding musical skill. Today the field is diversifying rapidly, but the vast majority of top orchestra jobs are still held by white men, and barriers, including financial ones, still exist.

Sirota’s generation of classical musicians has little patience for old modes and barriers. By launching the co-op, Sirota has effectively created her own path to studying conducting in an affordable, supportive and accessible way. And she’s bringing others along with her.

That first garage workshop was so successful (and just plain fun) that the group organized a second, which occurred late last November, this time at a donated rehearsal space at UCLA, where Sirota has served as artist in residence.

“Ultimately, we would love to do some fundraising,” she says. She’d like Rountree to be paid for his time and for the musicians to be paid more. “We are absolutely interested in scaling up, but in a way that still feels intimate.”

Like any good garage band, Liu, Rountree and Sirota are excited to move on to bigger and better spaces and grow as an organization, and they are equally determined to stay true to the supportive spirit of the co-op and their “rumpus room” roots.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.