- Share via

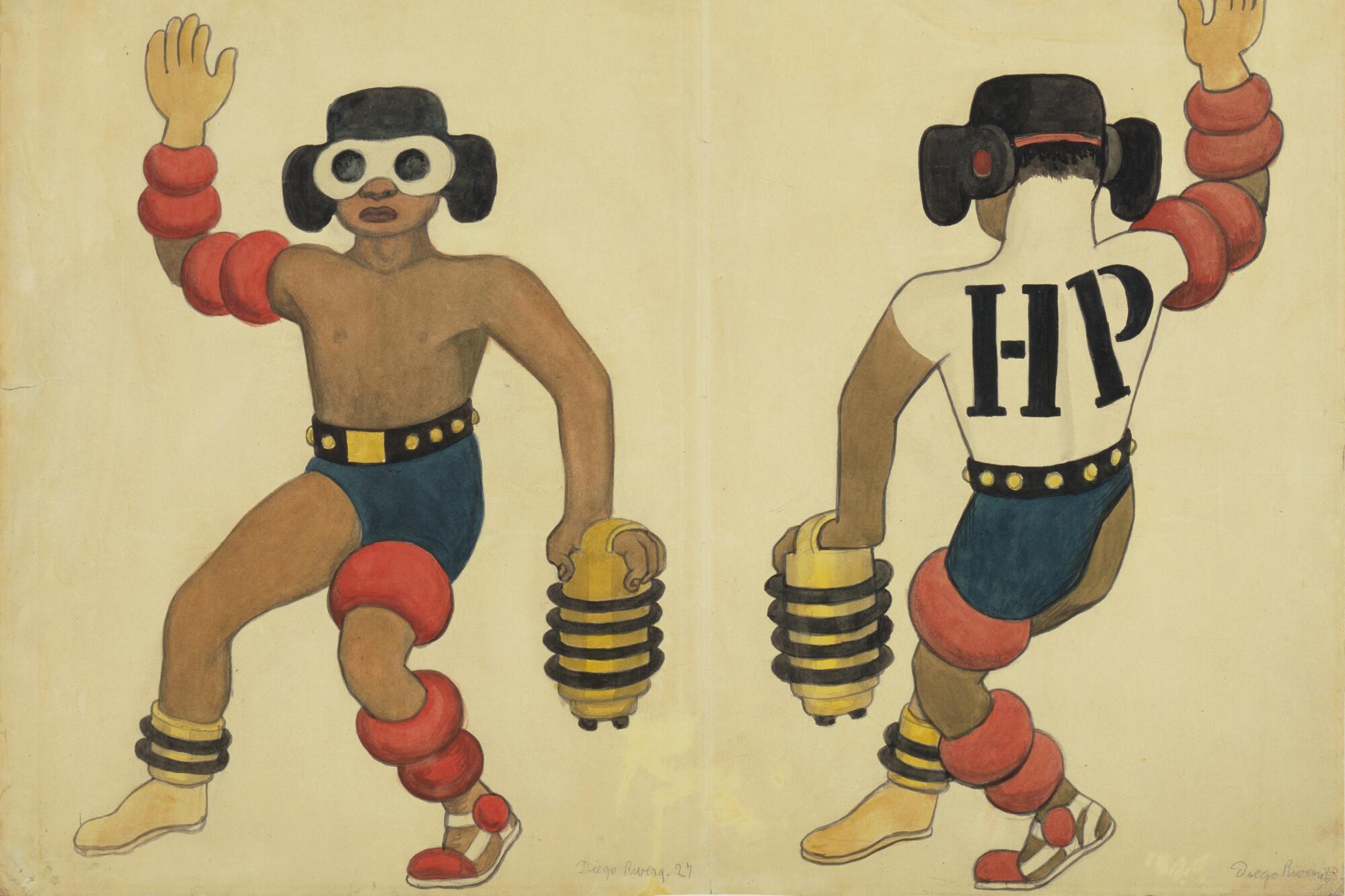

San Francisco — The year was 1932. The setting, a hall occupied by the Philadelphia Grand Opera. The event: a ballet titled “H.P.” for “Horsepower,” a dance that hasn’t been replicated since — probably for good reason.

“H.P.” featured an array of agricultural products (bananas, tobacco) dancing onstage with a company of sailors, a siren and various gold and silver nuggets. An advance dispatch in the Philadelphia Inquirer promised 10 pineapples and as many dancing swordfish. If Carmen Miranda ever had a Marxist fever dream about the flow of commodities from the global South to the industrialized North, it might have resembled this ballet.

Overseeing choreography of this danse bizarre was ballerina Catherine Littlefield; Mexican composer Carlos Chávez crafted the score. Serving as co-creator as well as costume and set designer was none other than Diego Rivera.

“H.P.” is a fascinating episode in the prolific career of the Mexican muralist, who is currently the subject of an expansive exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “Diego Rivera’s America” features more than 150 paintings, frescoes, sketches and drawings. It runs parallel to the museum’s long-term display of “Pan American Unity,” a portable 10-panel fresco Rivera painted in San Francisco in 1940 — his last mural in the U.S. It is being shown in SFMOMA’s free ground-floor galleries while the City College of San Francisco, where “Pan American Unity” typically resides, works on developing a new venue for it (an effort mired in financial and bureaucratic troubles).

The deep dives on Rivera make for compelling viewing in tandem with a separate exhibition in Los Angeles: “Reinventing the Américas: Construct. Erase. Repeat,” currently on view at the Getty Center, which gathers several centuries’ worth of prints, watercolors, bookplates and maps that explore how the concept of “America” has been depicted and defined. Together the shows offer an intriguing window into Latin American identity as it was constructed — and is now being deconstructed.

Before I set foot in SFMOMA’s galleries, I wasn’t sure I needed another Diego Rivera show. The artist materializes plenty in art museums, including the 2016 exhibition “Picasso and Rivera: Conversations Across Time,” held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The museum also hosted a major traveling retrospective of the artist in the late 1990s, “Diego Rivera: Art and Revolution.” Adding to the risk of deja vu is the fact that Rivera’s more picturesque pieces (all those flower sellers) have been rendered cliché by the mill of art merchandising.

But “Diego Rivera’s America” won me over on several points. Organized by guest curator James Oles with Maria Castro, SFMOMA’s assistant curator of painting and sculpture, the show zeroes in on the extraordinarily fecund two-decade period following the artist’s return to Mexico from Europe in the early 1920s. There is also the smart installation: Large-scale film projections of some of his murals offer a dynamic way to experience them in reproduction. In addition, the cartoons used in developing these installations are presented on plywood walls, creating the effect of a mural in progress — a simple yet striking design.

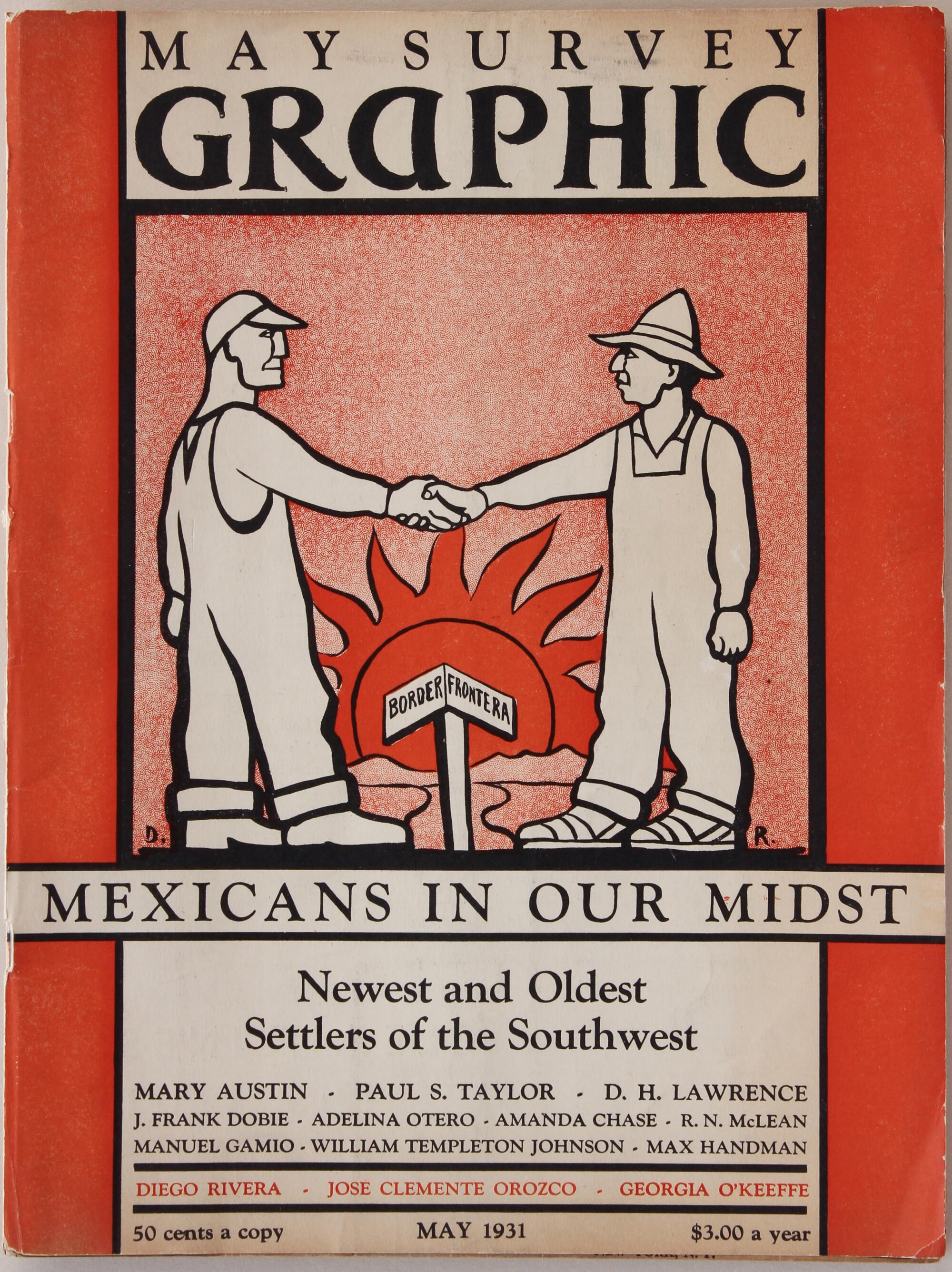

And then there are the revelatory tangents. These include samples of Rivera’s illustration work for the publishing industry (including very capitalist U.S. magazines such as Fortune), paintings from the late 1930s that dipped a toe into the surreal and, of course, that ballet — which appeared for one night only, failing to make much of an impression on the critics. (John Martin of the New York Times described the choreography as consisting “almost exclusively of nervous bits.”)

The story of “H.P.” may seem like a footnote. But embedded within it are ideas that make the show as a whole an intriguing enterprise at this moment. Amid the shimmying fruit was a character called “The Man” (interpreted by Russian dancer Alexis Dolinoff), who represents an intriguing hybrid: a biracial man who is also part machine and whose costume drew from Yaqui deer dancers as well as elements of industrial design. The Man is a sci-fi mestizo — and a prescient precursor to the machine-enhanced Mexican laborers of filmmaker Alex Rivera’s 2008 thriller “Sleep Dealer.”

The Vincent Price Art Museum is showing work by 30 sonic artists, from punk band Nervous Gender to experimental composers Raven Chacon and Guillermo Galindo

In fact, the way Rivera wielded identity — and helped define it — is one of the more intriguing currents in the show and the smart catalog that accompanies it.

In the wake of the country’s long and bloody revolution (1910-20), Mexican education minister José Vasconcelos tapped Rivera for a series of mural commissions in government buildings that were intended to recount the history of Mexico. They were also meant to present the figure of the mestizo (someone of mixed Indigenous and Spanish descent) as a binding national identity in the wake of fractious war. That identity, one that spans the American continent, is now under scrutiny — interrogated for being less about a union of cultures than an example of how European culture can simply vacuum up everything else.

Rivera’s work certainly didn’t shy away from depicting the violence and dispossession that led to Mexico’s mixed-race states. But his art is nonetheless foundational in equating modern Mexican identity with mestizaje. And his canvases of Indigenous people — flower sellers, village marketplaces and women bathing in rivers — not only romanticize rural Indigenous life, they subtly consign it to the past.

“Rivera’s omission of any evidence of modernity — electrical wires, advertisements, tourists — or even shadows,” writes Oles in the introductory essay, “could be seen as perpetuating stereotypes of Mexico as a tranquil, preindustrial utopia.”

In racist comments against Black and Indigenous people, Martinez exposed a blinkered tradition of defining the Latino community that may be on the way out.

To walk through the galleries of SFMOMA, therefore, isn’t simply to gain an understanding of how Rivera developed his mature style; it is to witness the construction of modern Latin American identity. It is also to glimpse the power structures embedded within that identity. Unnamed Indigenous people figure prominently in market scenes and as symbolic devices in murals; Rivera’s more formal, named portraits, meanwhile, depict a fair-skinned international elite.

If the Rivera show is about building identity, the exhibition at the Getty Center is intent on picking it apart.

Organized by curator Idurre Alonso of the Getty Research Institute, “Reinventing the Américas” is a delirious rabbit hole of an exhibition that shows how the concept of “America” (meaning the two continents) was devised by Europeans and reimagined periodically to reflect power shifts.

Riotous images of incredible flora and fauna (some of it invented) are fascinating for depicting the Americas as a region both fantastic and monstrous. These were used to entice European settlement as well as to justify it. Early colonial prints showed Indigenous people engaged in acts of so-called idol worship and cannibalism. Cue an unsettling 16th century Flemish engraving by Philippe Galle and Johannes Stradanus that depicts people roasting a human leg on a spit at the horizon.

Central to that image is a naked Indigenous woman sitting on a hammock. This is another colonial trope: America as naif on the verge of being “civilized” (a.k.a. ravaged).

This is not the first exhibition to explore the use of Indigenous people or symbols to craft an American identity. At the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., for example, curators Paul Chaat Smith and Cécile R. Ganteaume organized the ongoing long-term exhibition “Americans,” which looks at how Indigenous iconography has been deployed in the U.S. But the Getty’s show takes it a step further, inviting contemporary Indigenous artists into the gallery and giving them the space to react to the material on view.

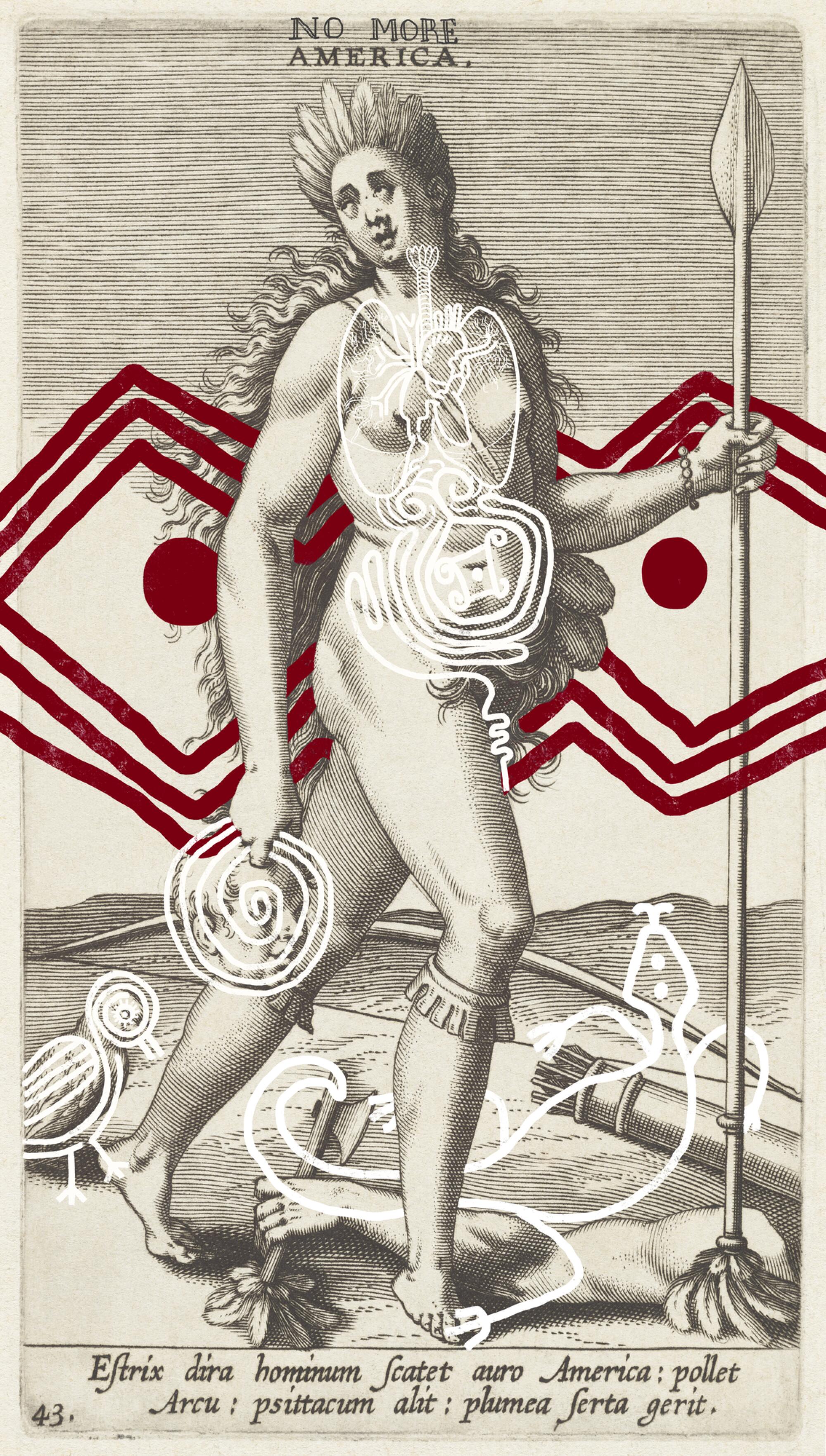

This includes, most prominently, a series of interventions by artist Denilson Baniwa, a Brazilian artist of the Baniwa ethnicity, who was born on the Rio Negro, about 200 miles upstream from Manaus. Baniwa has scanned some of the historic images featured in the show and digitally layered his own drawings over their surfaces. These have been magnified into wall-sized installations that dominate the galleries.

On a map of the New World, Baniwa crosses out European place names and replaces Western pictographic symbolics with Indigenous ones. A 17th century Dutch print of the last Inca emperor, Atahualpa, is altered to obscure the chains that bind him and replaces them with a dignified cloak. On a print showing yet another nude female allegory of America, he adds layers of pattern and alters the text above her head to read, “No More America.”

The museum also invited more than half a dozen Latino and Indigenous Angelenos to contribute wall texts about facets of the work that stood out to them. Jessa Calderon, an author and singer of Chumash and Tongva heritage, noted the relationship of Indigenous ornamentation to nature and the resilience of Native identity despite centuries of colonization.

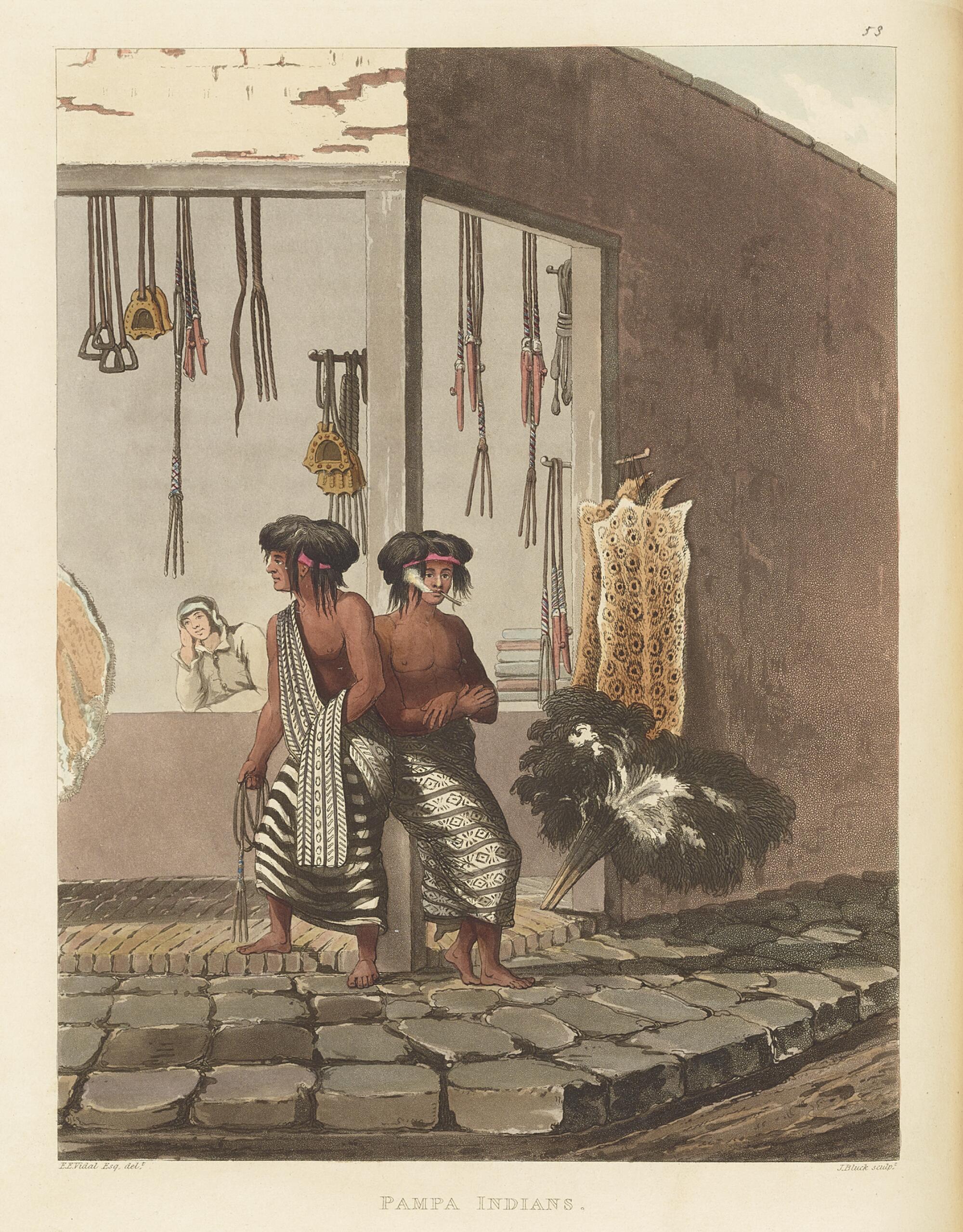

Look closely and you’ll find flashes of this Indigenous defiance throughout the exhibition. A 19th century British print shows a pair of Native people from the South American Pampas lounging casually on a street corner, wrapped in brilliant geometric textiles. A watercolor created that same century by the formative Peruvian painter Pancho Fierro shows a Christian religious procession peopled by Indigenous women in traditional dress.

The narrative of mestizaje preaches synthesis, frequently rendering the Indigenous symbolic, but the art on view at the Getty, alongside the Rivera show at SFMOMA, offers glimpses of a more complex reality — not just assimilation but continuity, survival.

‘ᎤᏕᏲᏅ (What They’ve Been Taught)’ explores expressions of reciprocity in the Cherokee world, brought to life through a story told by an elder and first language speaker.

Shortly after returning to Mexico from Europe, Rivera took a trip to the isthmus of Tehuantepec, where the dress and artistic traditions of the region’s Zapotec culture influenced him profoundly. In fact, a pair of dancers in clothing typical of the region appeared in “H.P.” (These influences also materialized in the work of his wife, Frida Kahlo, who often donned Tehuana dress and represented it in her art.)

If, in his murals, Rivera frequently depicted Indigenous people as archetypes, his studies reveal something more nuanced. A wall in SFMOMA’s galleries features a series of 1930s watercolors of Zapotec men, each clad in the simple garb of rural campesinos. One dons his straw sombrero on the crown of the head while another arranges it at a rakish angle; some look off into the distance while one man gazes peevishly at the artist.

The men go unnamed in Rivera’s work, but they come off as people, not symbols. They each have a story. One that is only now being considered.

'Diego Rivera's America'

Where: SFMOMA, 151 Third St., San Francisco

When: Through Jan. 3, 2023

Admission: adult/children $25/free

Info: sfmoma.org

'Pan American Unity: A Mural by Diego Rivera'

Where: SFMOMA, 151 Third St., San Francisco

When: Through Jan. 2024

Admission: adult/children $25/free

Info: sfmoma.org

'Reinventing the Américas: Construct. Erase. Repeat.'

Where: Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Dr., Los Angeles

When: Through Jan. 8

Admission: Free; advance reservation required

Info: getty.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.