Column: Is ‘The Patient’ a full-blown allegory for the pandemic, or is it just me?

- Share via

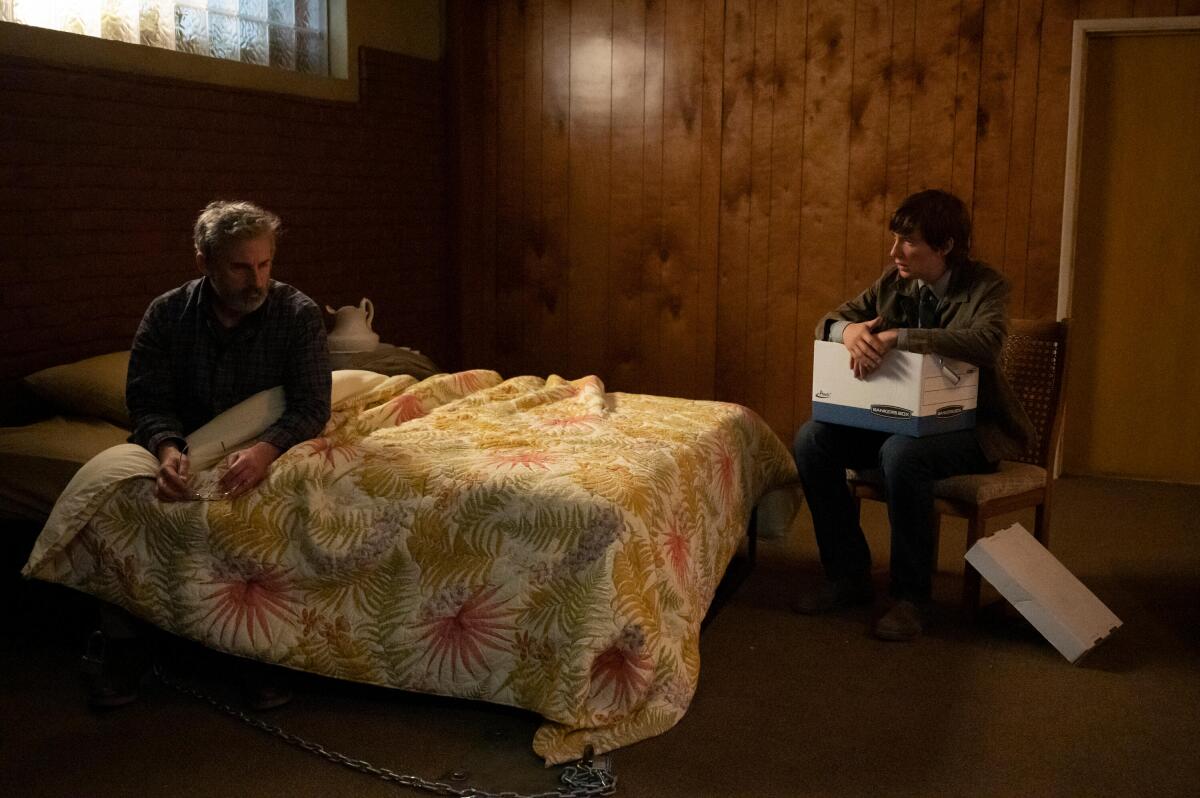

In the new FX for Hulu limited series “The Patient,” Sam Fortner (Domhnall Gleeson) abducts and imprisons his therapist, Dr. Alan Strauss (Steve Carell), in the hope that Strauss can cure him of his homicidal compulsions. The story can be, and has been, described in many ways — a psychological thriller, a black comedy, part of the recent therapy-show trend but with the ever-popular serial-killer twist.

As I watched, however, I couldn’t help thinking that it was the first real sighting of that elusive trend we’ve all been wondering about for the last two years — the post-pandemic narrative.

In mid-2020, when even people who were not epidemiologists began realizing that COVID-19 would not vanish or even become manageable in a matter of weeks or months, there was a lot of talk about what sort of visual storylines would emerge from this time of catastrophic death rates, global fear and near-universal closures.

There was, of course, an immediate impact. When film and television production was suspended, all manner of Zoom reunions, series and films sprung up to fill the void. Much of it was time-specific — visions of the entertainment industry rallying to lift spirits (remember John Krasinski’s “Some Good News”?) and prove that the show must go on (how adorable was it when Evie Colbert showed up on remote episodes of “Late Night With Stephen Colbert”?). Some of these pieces, like “Coastal Elites,” faded with their own immediacy, while others may well stand the test of time — “Host,” a remotely produced horror film, was and remains very scary.

Eventually, production resumed with social distancing policies that, among many other things, resulted in an abnormal number of scenes with three or fewer people in them and shows like “The White Lotus” confined to a single, sequestered location.

Some series, including “Grey’s Anatomy” and “The Morning Show,” chose to include the pandemic in their story lines but most did not. Post-apocalyptic series, including “Station Eleven,” suddenly seemed prescient even if they had been written when COVID-19 was still a gleam in some bat’s virus-infected eye.

A far-flung family, each member accustomed to doing exactly what he or she wants, finds itself suddenly brought together in reduced circumstances. How “Schitt’s Creek” unwittingly became a map of life at home amid the pandemic.

Beyond the logistics lay a bigger question: What kind of stories would emerge from the horror, the social cataclysm and all the deeply personal fallout caused by a pandemic?

Maybe one in which a man is imprisoned in a bedroom where he is forced to work, in extremis, while constantly worrying that the creature randomly killing people in the outside world might wind up killing him?

Or am I projecting?

I reached out to the show’s creators, Joe Weisberg and Joel Fields, and asked whether “The Patient” was in any way an allegory for the pandemic or if I was, you know, crazy. As you might expect from the writers of a therapy-centric show (or the spy drama “The Americans”), their reply was maddeningly opaque; they don’t want put their “own definitive statement on some things we very much want to leave open to interpretation.”

In other words, how does it make you feel?

Well, it makes me feel a lot of things, many of them disturbingly reminiscent of the trauma we’ve all been through. If “The Patient” is not a clever attempt to turn the familiar relationship between a killer and his frenemy into a commentary on the pandemic, then it accidentally hits a lot of evocative notes.

“The Patient” is not filmed on Zoom, or even solely in the bedroom in which Strauss is chained. Though essentially a two-hander, it is not as insular as, say, “In Treatment.” There are other characters — Sam’s mother (Linda Emond), Alan’s wife (Laura Niemi) and son (Andrew Leeds) — and we see Sam at his job and, later, Strauss’ family looking for him.

But when, early on, Strauss tells Sam that his plan is not going to work because therapy requires a safe space rather than one filled with threat and anxiety, it’s difficult not to hear the anguish of workers of all types as we lost control of our daily lives and attempted to carry on while all around us people sickened and died.

The reality of 2021 was both gentler and messier than the apocalypse fiction we consumed. But those stories taught us we can survive anything

Though not literally chained to the floor, many of us woke up one morning to a world narrowed to the perimeters of our dwellings, dependent, like Strauss, on deliveries of food and other necessities. (Sam’s delight over the takeout he offers his captive every evening echoed our silver-lining pandemic gestures — Hey, let’s support all our local restaurants by eating more takeout!)

The sudden detachment from ordinary outside life forced and/or allowed many to contemplate their own psyches with a thoroughness that was impossible in the bustle of the old times. That is the point of “The Patient,” which is so interior that its interiors have interiors. Strauss doesn’t just flash back to memories of his family, which include conflict over his son’s move from Reform to Orthodox Judaism. He also imagines himself at Auschwitz and in conversation with his own dead therapist (David Alan Grier).

The story turns on Sam’s belief in a quick turnaround; the problem acknowledged will now be solved, lickety-split, by the expert he has procured. He is shocked to learn that the process will involve not weeks, not months, but years.

Which is where many of us found ourselves in 2020 and 2021 and 2022. After almost three years since COVID-19 began infecting humans, we are still attempting to balance our desire to be “normal” with all the effort, time and setbacks that will involve.

Obviously, this could all be in my head, just like so many things are all in Strauss’ head, or Sam’s. But even Sam’s impetus to kill feels very … contemporary. While it doesn’t take a therapist to realize that Sam’s compulsion is rooted in years of abuse by his father, he may be the first serial killer triggered by personal irritation.

Like the Challenger disaster, the Oklahoma City bombing and the fall of the Twin Towers, Jan. 6 is a fixed point on this country’s timeline.

He is not interested so much in the act of killing as by the need to take revenge on those who have offended him. People who by word, look or deed have demeaned him or done things he does not think are fair.

Looking at it one way, Sam is a product of grievance culture; say something he doesn’t like or give him a funny look, and he’ll kill you. Strauss wonders whether Sam isn’t looking for a reason to be offended, reminding him that offense can often be unintentional or misinterpreted — and even if it is not, “we are all broken vessels” who deserve consideration as fellow humans.

Grievance culture certainly existed before the pandemic, but it was fanned by disagreements over basic science, public policy and underlying political divisions. Mired still in the pandemic’s tragedy and trauma, we are all at some level thrashing about in search of a single source for our pain in hopes of fixing it. If the subsequent rise in general rage and mass shootings is an indication, our year or so of forced distance did not make our hearts grow fonder.

It does, however, in Strauss’ case. The brightest thread in “The Patient” (beyond many moments of smart writing and very fine acting) is the sight of the doctor healing himself. Just as the pandemic revealed many hard truths about work inequality, the demands of parenthood, hustle culture and attitudes toward mental health, Strauss’ time in mortal-fear lockdown forces him to re-evaluate the story he has been telling himself about his own relationship to work and family, particularly his estrangement from his son.

Many of those who reviewed “The Patient” took issue with its length. Though the episodes are 30 minutes or less, the story does feel a bit stretched out and occasionally repetitive, with no clear ending in sight.

Which, of course, only proves my point.

With a tidal wave of limited series swamping every streaming service, Hollywood once again proves that too much of a good thing is bad for business.

‘The Patient’

Where: Hulu

When: Any time

Rating: TV-MA (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 17)

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.