Review: The high-octane ‘Tambo & Bones’ scrutinizes the inescapable legacy of minstrelsy

- Share via

Minstrelsy should be vociferously condemned but its centrality in American culture cannot be denied. “Jim Crow,” the name associated with the laws and practices of racial segregation, comes from a character developed by Thomas D. Rice, who’s been called “the father of American minstrelsy.”

“Jumping” Jim Crow purportedly was based on an actual enslaved person Rice claimed to have seen singing and dancing with what was later described by a theatrical colleague as a “laughable limp.” The heartlessness of this phrase perfectly sums up the cruelty of a once-popular, now proscribed entertainment that always seems to be bubbling up from the collective American unconscious.

In her short, useful book “Blackface,” scholar Ayanna Thompson defines American Blackface minstrelsy, which arose in the early 19th century and took off after the Civil War, “as a specific comedic performance tradition that according to its own logic, imitates, celebrates, and mocks the actions of Black Americans.” The point is to subjugate and humiliate under the guise of amusement.

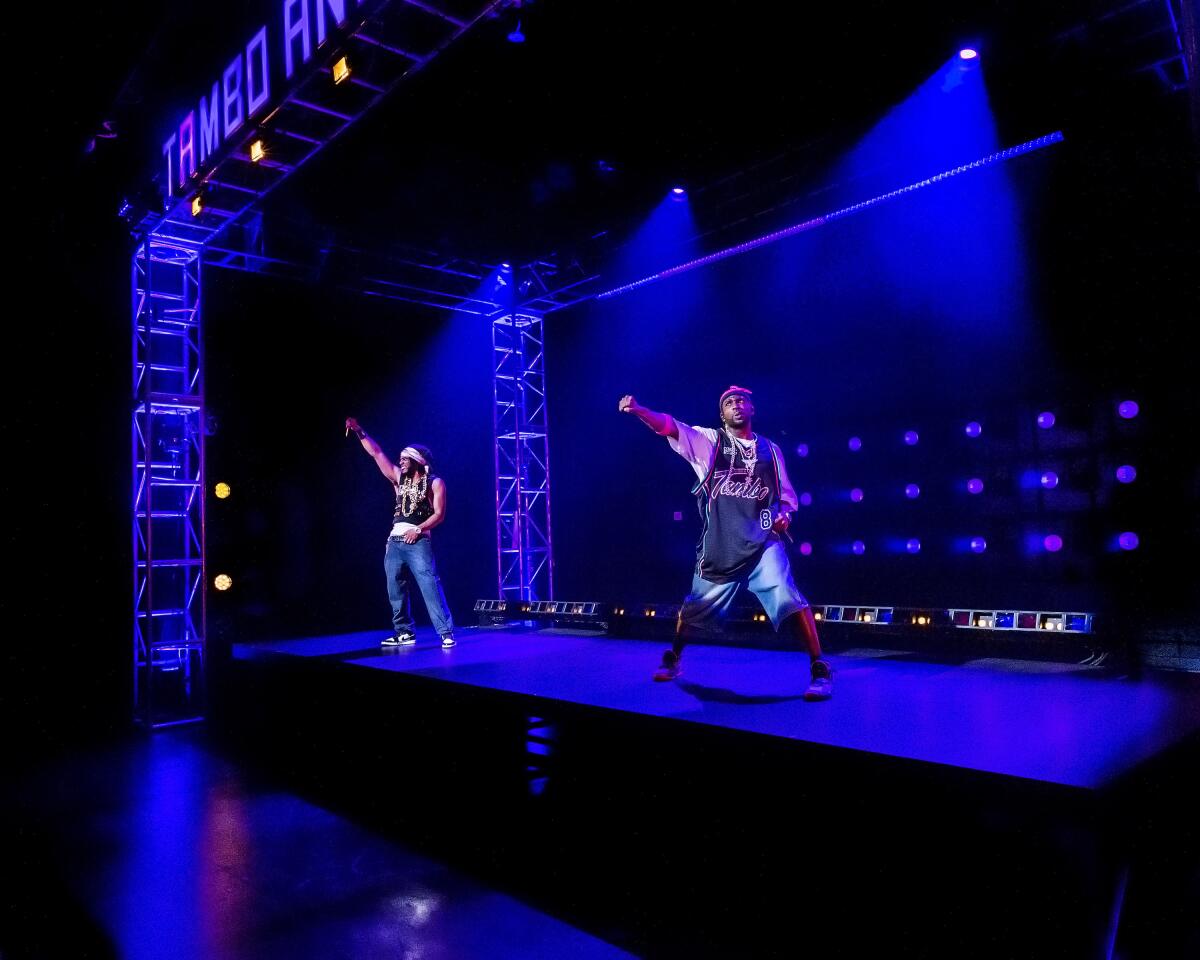

“Tambo & Bones,” a new play by Dave Harris that opened Sunday at the Kirk Douglas Theatre, scrutinizes the inescapable legacy of minstrelsy in Black entertainment. At the start of this rambunctious 90-minute production, two Black performers who are well-versed in minstrel shtick are hoping a white audience will be delighted enough by their routines to toss them some quarters. (The racial composition of the audience before which “Tambo & Bones” is performed naturally changes how this plays out.)

Dressed like vagabonds on a set with fake pastoral scenery, Tambo (W. Tré Davis) and Bones (Tyler Fauntleroy) are trying to give a paying white crowd what it wants. What exactly do these spectators want? To feel superior, of course. But how?

Michael R. Jackson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning musical triumphantly arrives on Broadway.

Pratfalls aren’t bringing in any coins. Bones makes up a sweet story about a fake son. That doesn’t work. He does some dangerous tricks, but still nothing. He decides to show them his pain. Surely an appeal to their empathy will translate into a cash reward. Think again.

Tambo suggests a more intellectual approach. A treatise on race in America is his gimmick. But his lecture, which starts with the Middle Passage and ends with Barack Obama, leaves him empty-handed.

The two men clown around onstage like the tramps in Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” or the young men talking smack on a street corner in Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu’s Beckett-inspired play “Pass Over.” In keeping with these precedents, there’s a furious tension between Tambo and Bones but also an inseverable connection.

Metatheatrically restless, “Tambo & Bones” takes a page out of Luigi Pirandello’s “Six Characters in Search of an Author.” In rebellion against their playwright, Tambo and Bones drag the person responsible for placing them in this nutty minstrel show onto the stage and attack him. (A dummy, dressed in bookishly nerdy clothes, stands in for Harris.)

The setting for the second movement of the play is a concert. Tambo and Bones have moved from the minstrel past to the more recent hip-hop present. But the battle continues not only about what sells but what can legitimately be put up for sale.

Performance styles radically change but conflict between Black artists and white audiences remains unsettled.

Bones knows that without money there can be no power. But Tambo wants to burn the system to the ground. It’s an old debate — a version of the Black Power movement challenge to the Civil Rights movement — dressed up in new clothes and viewed through a feverishly theatrical lens.

The execution is high-octane but I regretted that the lyrics were often lost in a blur of sound. Knowing that Harris is also a poet, I didn’t want to miss a word. But “Tambo & Bones” is more conceptually impressive than carefully worked out.

The production, directed by Taylor Reynolds, surges with more raw theatrical power than precision. Davis’ Tambo and Fauntleroy’s Bones never let up. The audience is encouraged to make some noise, but the unflagging energy of the performers doesn’t translate into quickening interest.

The play’s third section, which moves Tambo and Bones into the future, is the most daring. It’s also the fuzziest.

White robots (played by Tim Kopacz and Alexander Neher) are brought out and there’s chilling talk of a race war and genocide. Historical patterns recur in unexpected ways. But allegorical distance muffles the shock.

Alfred Jarry, the French writer best known for his wild ride of a play “Ubu Roi,” said that a playwright should “unleash” his character onto the stage. That is the effect Harris achieves, for better or worse, with Tambo and Bones, who are fated by history to perform for their very lives.

'Tambo & Bones'

Where: Kirk Douglas Theatre, 9820 Washington Blvd., Culver City

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays. Ends May 29. Call for exceptions.

Tickets: $30-$75 (subject to change)

Information: (213) 628-2772 or centertheatregroup.org

Running time: 1 hour and 30 minutes with no intermission

COVID protocol: Proof of full vaccination is required. Masks are required at all times. (Check website for changes.)

“A Strange Loop” leads the 2022 Tony nominations, with a strong showing in the play category for “The Lehman Trilogy.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.