Review: In a smashing new LACMA retrospective, Barbara Kruger probes the modern media maelstrom

- Share via

Barbara Kruger has a way with words. Big, bold, often visually loud words.

Kruger mixes exceptional graphic design skills with deep knowledge of the structural complexities of art and language, not to mention the media maelstrom in which modern life is lived. For 40 years, the L.A.-based artist has surveyed the social, cultural and political landscape with a deft combination of acute insight and lacerating wit.

No stranger to the city’s museums, where her work has been prominently featured at the Museum of Contemporary Art (a terrific 1999 midcareer survey, plus two incisive building murals), the UCLA Hammer Museum (a blaring 2014 entry installation) and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (a somewhat less successful 2008 commission for the three-story elevator shaft inside BCAM, too busy for the available space), the artist is now the subject of a smashing LACMA retrospective.

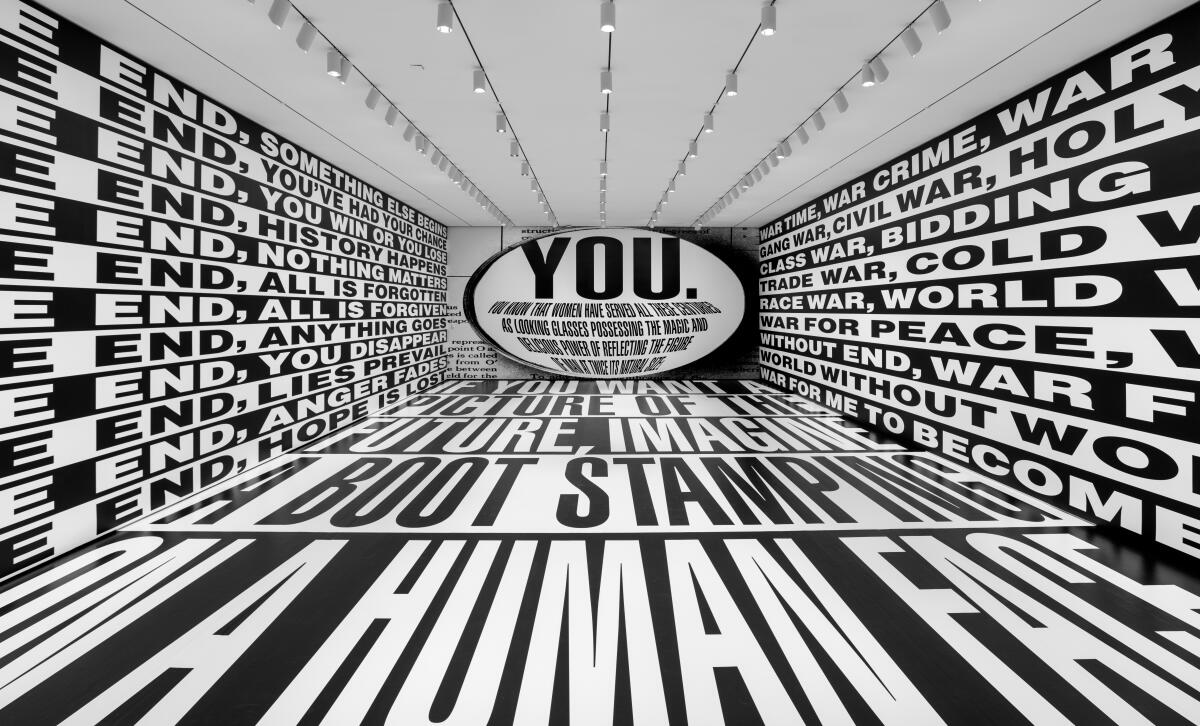

In the show’s title, “Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.” (with Xs over the “you” and “me”), the equivocal shifts that ricochet among the personal pronouns “I,” “you” and “me” pry open a space of transparency in which the artist lets viewers know to watch out for the slipperiness of what they are about to see. Who is speaking, who is listening and who oversees — or benefits from — the exchange is not as clear or simple as one might assume.

Take “Untitled (Truth),” a 2013 digital print on a sheet of vinyl almost six feet high and 10 feet wide. A pair of hands pulls apart a stretchy elastic bandage overprinted with the word “truth,” all in capital letters in conventional Helvetica typeface. Somewhere between a billboard and a mural, the sign confounds in a productive and probing way.

Is the elasticity of fact, reality or certainty under urgent examination? It would seem so. The crimson word printed over a field of bright green causes a jangling chromatic dynamism of opposites on the color wheel, creating a purely visual sense of alarm.

The hands belong to a businessman, judging from the glimpse of shirt cuffs and suit jacket. So is this a knowing reference to the power of patriarchy to define — and manipulate, disfigure or distort — veracity?

Lustrous fingernails are manicured and buffed, a distinct inference of social class, while the function of a compression bandage is to bind up wounds and aid in healing. Has the dominion of masculine corporate affluence impaired reality?

That bandage is being stretched and twisted, but the flat, clean, vivid red word is not warped or misshapen in the least. Is the stable truth it declares the one being pictured in Kruger’s carefully crafted imagery, over which it is superimposed?

The gallery floor where the work is installed further mixes up the message. Initially puzzling descriptions of unseen pictures are featured in a wall-to-wall vinyl text of white letters on a red ground. All relate to the human body.

“The vomiting body that screams ‘kiss me’.”

“The praying body that whispers ‘save me’.”

“The numb body that mumbles ‘shock me’.”

The text, printed on the floor of a large room, can be read only by moving around the space and shooting darting glances between the legs of other museum visitors. Their physical bodies — and your own — get entangled with those pictorial references to bodily experience, bringing a ghostly, incorporeal picture home.

Disembodied experience is now commonplace in contemporary life — a truth — as anyone looking into the flickering light of a cellphone screen can attest. (“Feel is something you do with your hands,” insists another large digital print on vinyl, its image showing a woman’s exquisitely manicured hand hovering over a deathly X-ray of skeletal bones.) One primary difference between this survey and Kruger’s MOCA midcareer retrospective almost a quarter-century ago is that, in the interim, an analog image universe has been almost totally transformed into a digital one.

Kruger has been revising and adjusting things accordingly. One great thing about her work is the way she starts with a visual environment already familiar to the audience. She neither complains about nor dodges the mass media context, instead unpacking it for us.

Born in Newark, N.J., in 1945, Kruger went to art school only briefly, gaining most of her media education through a combination of hands-on experience and independent curiosity. She read widely while working in New York as a graphic designer and picture editor for commercial magazines, including Mademoiselle and House & Garden.

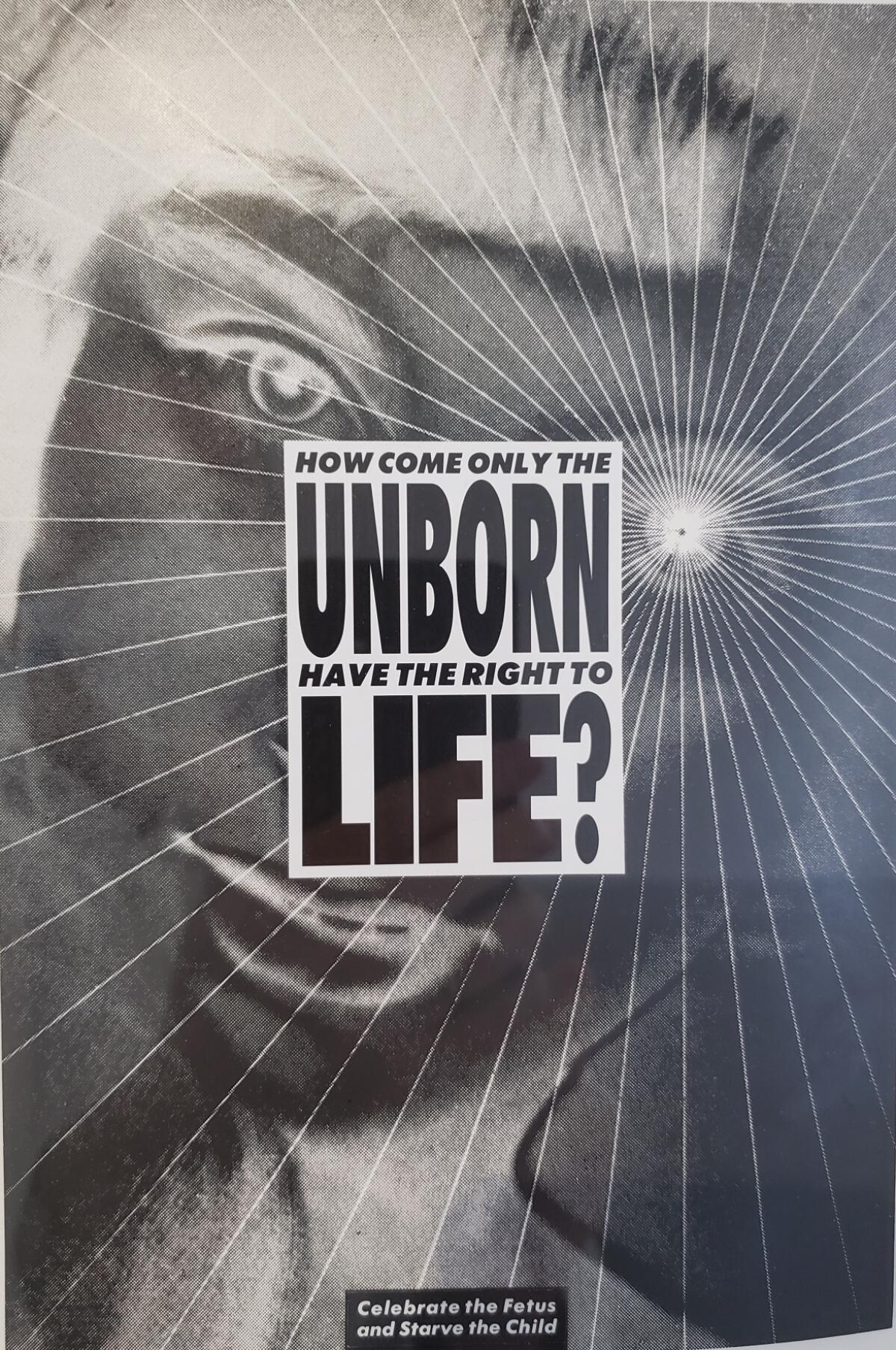

Across Wilshire Boulevard from LACMA, in a show at Sprüth Magers gallery, 20 collages for the early-1980s work that made her famous are straight-forward paste-ups of the sort once regularly used in commercial publishing. (The collages were shown within the retrospective during its debut last fall at the Art Institute of Chicago, but LACMA didn’t have enough space.) Mostly, she employs variations on a sans serif typeface called Futura, created in 1927 by German designer Paul Renner, later persecuted by the Nazis. Among the collages are some of her classics, including paste-ups declaring, “Your body is a battleground” and “How come only the unborn have the right to life?”

In the late 1970s, she began to incorporate techniques of abstraction and typographic eccentricity pioneered by Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and others of the early 20th century Russian avant-garde. Their brilliantly adventurous graphics were “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste,” as poet David Burliuk famously put it in a 1917 manifesto.

Kruger, however, avoids such oppositional positions. Instead, she drew on Pop, Minimalist and Conceptual art of the immediately preceding generation to understand and question, in her words, “the systems that contain us.”

Not only has the strategy been successful but it has also inspired legions of amateur copycats. The show’s witty opening gallery features a slew of them.

In recent years, society’s digital transformation has meant reconceiving earlier works for new digital presentations. The show has many examples — among the most effective a 2020 video version of 1988’s “Pledge,” which runs slightly longer than a minute.

Rather than X-out and replace words in the American Pledge of Allegiance for a static graphic, like an editor with a blue pencil crossing out a text until the right word is found, she digitized the evolving process. To the relentless, rhythmic beat of a tick-tock soundtrack, words unfold on the video screen.

Beginning with “I pledge allegiance,” the last word is supplanted by the sequence “adherence – adoration – anxiety – affluenza – I pledge allegiance to the flag…” You think your way through a vow you can probably recite by heart, stumbling across unacknowledged sentiments and, elsewhere as the text continues, even shocking cruelties and bigotries. Finally, you arrive at a fuller understanding of your participation in the construction of a social contract.

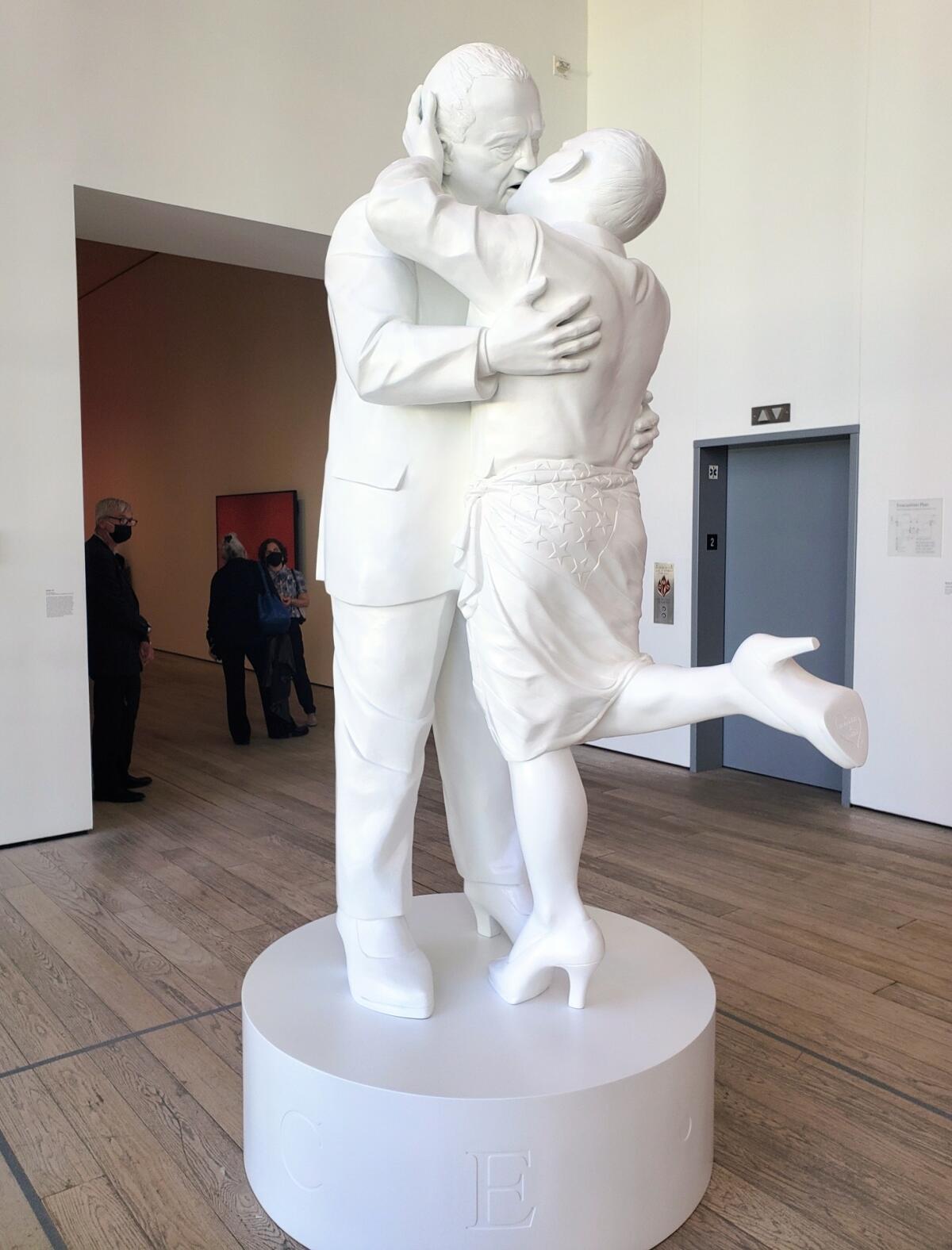

Digital ephemerality runs up against “Justice,” an inert 1997 statue in white-painted fiberglass. FBI strongman J. Edgar Hoover, known to use secret files of illicit sexual activities to control politicians, is depicted with closeted homosexual lawyer Roy Cohn, brutal mentor to Donald Trump, who engineered the mass dismissal of gay government employees during Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s early 1950s “Lavender scare.”

Kruger’s composition recalls Alfred Eisenstaedt’s famous 1945 photograph of a sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square on V-J Day. Hoover and Cohn, who is wrapped in an American flag skirt and kicking up a high-heeled pump, are about to lip-lock in an amorous embrace.

“Justice” mocks the Eisenstaedt’s celebratory pose. A throwback to pristine 19th century American neoclassical statuary, which idealized establishment values of morality and virtue, the statue asserts that liberation from fascist threat was hardly enjoyed by everyone — then or now.

The show was jointly organized by the Art Institute of Chicago, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (where it travels in July) and LACMA, where it is overseen by Director Michael Govan and curator Rebecca Morse. Rather tight in its current incarnation, featuring just 33 works, it includes printed vinyl panels, full-room installations, single-channel videos, large-scale LED videos and wallpapers.

It is accompanied by a catalog with two unusual features — both valuable.

One is an absorbing 12-page opening sequence of documentary photographs of Kruger murals, billboards and magazine designs dating from the period of COVID-19 pandemic closures and the months of public protests following the murder of George Floyd. It is disconcerting to see armed soldiers patrolling in front of MOCA’s Kruger mural pondering “who is beyond the law.”

The other is a 30-page closing sequence of previously published essays by a variety of writers, which Kruger used as a classroom syllabus when she taught for many years at UCLA. The subjects range from economics and identity politics to sexuality and comedy.

For an artist whose work relies on the tensions between image and text, the photographs and essays are a catalog framing device of exceptional insight. Together, they evoke an artist successfully determined to locate her work outside the hothouse environment of an often-parochial art world.

My husband’s favorite T-shirt is a Kruger design with the pertinent legend: Belief + Doubt = Sanity. Wise words for ordinary daily life, especially in a media-saturated environment filled with dubious promises.

'Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.'

Where: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles

When: Through July 17. Closed Mondays

Info: (323) 857-6000, www.lacma.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.