Timpanist and composer William Kraft, who helped usher in the modern L.A. Phil, dies at 98

- Share via

William Kraft, a percussionist, composer, conductor and educator who played a long and indispensable role in making Los Angeles a world capital of new music, died Saturday at USC Verdugo Hills Hospital. His wife, composer Joan Huang, says the cause was heart failure. He was 98.

Kraft was the right percussionist at the right time in the right place. As a composer, he embraced the unique music opportunities that the world of percussion presented. As a performer, he took full advantage of the varied opportunities unique to the musical life in Los Angeles, which included a decadeslong career with the Los Angeles Philharmonic as percussionist, principal timpanist, composer-in-residence and associate conductor. He was the founding conductor of the L.A. Phil New Music Group, which, with its Green Umbrella concerts, helped transform the notion of what a modern orchestra could become.

In the 1960s and 1970s, during the heyday of Zubin Mehta’s L.A. Phil music directorship, Kraft’s timpani were an unmissable component in what became Mehta’s vibrant orchestral “L.A. sound.” At the same time, Kraft involved himself in the wider L.A. new music scene. He was a regular at the Monday Evening Concerts and the Ojai Music Festival. He became Igor Stravinsky’s go-to percussionist. He befriended and gave the premieres of major works by many of the leading avant-gardists of his time.

Yet Kraft was also happy to take advantage of all Hollywood had to offer. Among his several film and television scores, he delivered a majestic “Rocky Mountain” symphony of a soundtrack for the 1978 disaster feature film “Avalanche” that added impressive stature to its stars, Rock Hudson and Mia Farrow.

The same year and at the other extreme, Kraft translated the delicate effects of light and shadow reflected through the branches of a magnolia tree into a quiet piano piece, “Translucence,” that represented what he liked to call his American Impressionist side. He had an American Expressionist side, as well, that he was not as eager to acknowledge.

The infinite variety of percussion made all this possible. He grew up in the era when percussion was evolving from mainly providing punctuating sound effects in the orchestra to becoming solo musical discourse in its own right. For Kraft, percussion instruments produced the kinds of sounds that color our existence, while the emphasis on rhythm could illuminate interpersonal musical interactions. In his role as timpanist in the L.A. Phil, he provided the heartbeat of the orchestra, and in his politically themed works, he expanded that notion to having percussion signify the heartbeat of a just society.

In Kraft’s many solo, chamber and orchestral works, including a number of concertos for percussion soloists, he invariably put percussion front and center. Percussion, in the meantime, regularly put the timpanist front and center of the L.A. Phil. Kraft whacking away at the beginning of Mehta’s 1968 L.A. recording of Richard Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra” enticed countless counterculture college students at the time to wear out their LPs.

“You cannot imagine what it meant to stand there,” the celebrated British conductor Simon Rattle, who was trained as a timpanist, said of his first time conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1979, “and — ‘Oh, my God’ — it’s Bill Kraft!”

“He was a childhood idol of mine,” Rattle continued in a telephone call from his home, “an unsung master who understood the essence of percussion.

“And one of the sweetest people on the planet.”

William Kraft was born Sept. 6, 1923, in Chicago. His parents were Russian émigrés who had changed their name from Kashareftsky to Kraft and who moved to California when their son was 3. Kraft’s early training was in piano and percussion at San Diego State College (now University) and UCLA. During World War II, he served overseas in the military as a pianist, drummer and arranger in army bands, and he briefly played in jazz bands after the war before embarking on a serious musical career. That led him to study conducting with the young Leonard Bernstein at Tanglewood in 1948, composition with several noted composers (including the West Coast maverick Henry Cowell, one of the first composers to write for percussion ensemble) at Columbia University and timpani at the Juilliard School.

Kraft began his career as an orchestra percussionist with the Dallas Symphony in 1954 and then joined the L.A. Phil a year later. This was a somewhat lackluster period for the L.A. Phil, the last season of the conservative American music director Alfred Wallenstein, followed by a few directionless years until Mehta took over.

But Kraft quickly became a mainstay of the otherwise-burgeoning musical life of the city. In 1956, he enlisted other members of the L.A. Phil percussion section to form the First Percussion Quartet, so named because it was the first such ensemble. Later enlarged, it became the Los Angeles Percussion Ensemble and Chamber Players and promoted a wide range of new and recent percussion music by Edgard Varèse, John Cage, Lou Harrison, Cowell, Kraft and many others.

At the Monday Evening Concerts, he played in the American premieres of Pierre Boulez’s seminal “Le Marteau sans maître,” nailing the rhythmic complexity that few other percussionists could manage to Boulez’s satisfaction, and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “Zyklus,” which became one of the most famous percussion pieces of the second half of the 20th century. Stravinsky chose the percussionist for his recording of “The Soldier’s Tale” with narration by Jeremy Irons. Stravinsky became a seminal influence on Kraft’s own music.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

Meanwhile, at the L.A. Phil, once Mehta began, he was quick to appoint Kraft principal timpanist. Mehta was also drawn to Kraft’s music, he says from Tel Aviv, where he is conducting the Israel Philharmonic. In 1968, Mehta premiered Kraft’s Concerto for Four Percussion Soloists & Orchestra, a percussion phantasmagoria so colorful that it proved a hit despite its many Modernist elements.

“We were on the same wavelength musically and politically,” Mehta says, recalling his once having enlisted Kraft to help him devise a special concert in memory of Malcolm X after his assassination in 1965. The idea was to commission works, each marking a chapter in Malcolm X’s life, from five prominent African American composers.

“The board was very conservative,” Mehta says, but he and Kraft were defiant. To Mehta’s disappointment, though, he says they were not able to convince the composers to accept the commissions, so fraught and risky was the political climate. But Mehta later commissioned a new piece from Kraft that reflected the ongoing protests against the Vietnam War and the racial unrest in the spring and summer of 1967.

Kraft’s bold, angry “Contextures: Riots — Decade ’60” had its first performance on April 4, 1968, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion only hours after Kraft learned of Martin Luther King Jr.‘s assassination that same day. On the spot, Kraft added a new ending that quotes “We Shall Overcome,” played by an offstage jazz band that is used as part of the orchestral work. In another innovation, the “Contextures” performance included two abstract films that contextualized the era.

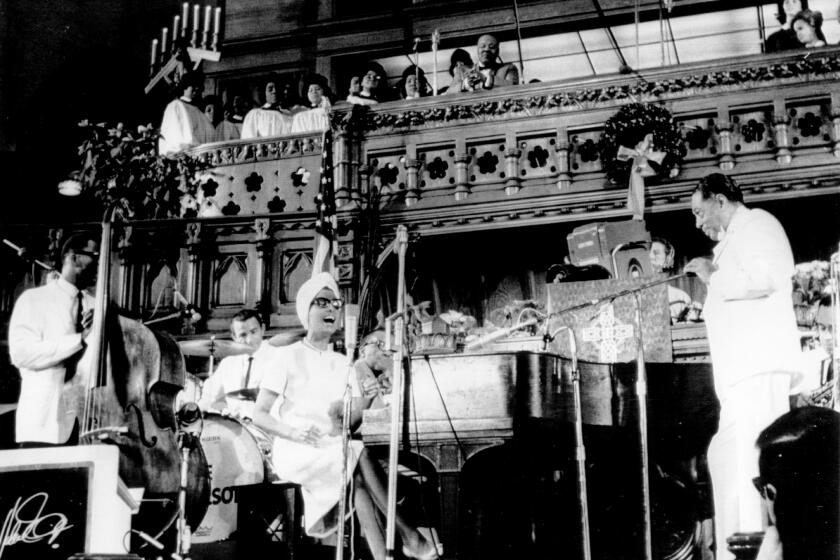

Along with composing, Kraft gradually developed his conducting skills, mainly leading new works. In 1966, he conducted the L.A. Phil in what became a historic Duke Ellington program at the Hollywood Bowl, with Ellington as the soloist in his piano concerto “New World A-Comin’.” From 1969 to 1972, Kraft served as the orchestra’s assistant conductor as well as its principal timpanist.

The L.A. Phil adeptly performed Ellington last weekend. Still, we don’t know what to do with the composer beyond keeping his best-known tunes in rotation.

In 1981, after 18 years as principal timpanist, the L.A. Phil appoint Kraft the first L.A. Phil composer-in-residence. He and writer Barbara Kraft decided to divorce the year before after 30 years of marriage. Kraft sold his percussion instruments and decided to see if he could survive as a full-time composer. For the next four years, besides composing, he formed and led the L.A. Phil New Music Group, which began the orchestra’s dedicated series of new music concerts, an idea that has become widely adopted by a number of orchestras in America and Europe.

Kraft ended his 30-year employment with the L.A. Phil in 1985, the year André Previn became music director, but his association with the orchestra continued through the rest of his life. Previn premiered and recorded “Contextures II: The Final Beast,” a sequel to Kraft’s first “Contextures” that features a solo soprano and tenor, along with a boys choir, and uses a selection of anti-war texts from ancient to modern times. His works continued to be played during the music directorships of Esa-Pekka Salonen and Gustavo Dudamel.

“I instantly liked Bill for many reasons,” Salonen, who made his L.A. Phil debut in 1984, said Sunday upon learning of Kraft’s death.

“He was a kind of intellectual, interested in the 12-tone techniques but without the taste of paper, because he was a musician who had performed some of the thorniest pieces. He always had the respect of the performers. They knew that he knew that they knew.”

For Salonen, who arrived in L.A. as something of a young, thorny European Modernist composer himself, that was a strikingly refreshing notion. In addition, the New Music Group was no small attraction for him to later accept the invitation to become the L.A. Phil music director in 1992. The L.A. Phil celebrated Kraft’s upcoming 80th birthday in 2003 by commissioning a Concerto for English Horn and Orchestra, “The Grand Encounter,” written for the orchestra’s English horn player, Carolyn Hove, and conducted by Salonen. In the Dudamel era, composer John Adams, the L.A. Phil creative chair, conducted and recorded Kraft’s Timpani Concerto No. 1 from 1992.

Salonen sees Kraft as a composer who on some level held on to his progressive roots, “but in his later years, his palate became more extensive. He got freer and freer as he got older, which is a nice trajectory.” That trajectory is most thoroughly followed through Kraft’s “Encounters” series.

Beginning with a solo tuba piece written in 1966 for the “Encounters” new music concert series at the Pasadena Art Museum, Kraft went on to create 15 chamber music scores over the next 42 years that explored the interactions of soloists or small ensembles with percussion and sometimes electronics. In them, he looked at percussion in its many aspects, and through them, life and spirituality and nature and aging.

“Encounters III” is a musical duet between trumpet and percussion. “Encounters VII: Blessed Are the Peacemakers” for chamber ensemble and percussion uses the opening of anti-war poems translated into morse code as rhythmic impulse. The final “Encounters XV,” for guitar and percussion and given its premiere by Southwest Chamber Music at the Colburn School in 2008, saw the 85-year-old composer in quiet meditation, its sounds meant for lingering, not conflict.

Southwest released a recording of all but the 11th of the series the following year that, taken as a whole, is the autobiography in music that Kraft never gave us in words. If he had, that would have been a history of the musical life in L.A. over more than six decades.

After leaving the L.A. Phil, Kraft began another career, in education. He taught at UCLA, where he met Joan Huang, his future wife, and became chairman of the department of musical composition at UC Santa Barbara. But most of his time remained devoted to composition. Many of the major American orchestras, along with ensembles in Israel, Korea, China, Australia, Russia and Europe, commissioned him to create percussion-extravagant orchestral scores. In 2005, Michael Tilson Thomas, another longtime Kraft colleague, and the San Francisco Symphony premiered a Second Timpani Concerto, which, along with his first, has already become a repertory piece for timpanists everywhere.

But Kraft also caught the attention of such divergent commissioners as the Kronos Quartet, the U.S. Air Force Band and United Airlines. For the latter, he wrote Modernist music to accompany travelers as they wheeled their luggage and lugged their backpacks through the kaleidoscopically lit United Airlines tunnel at Chicago’s O’Hare airport. Although United eventually replaced Kraft with Gershwin, for a period the tunnel became a reason for new music lovers to try to change planes in O’Hare when feasible.

Through it all, Kraft remained a presence in L.A. up to his last days. He was given rousing ovations when his music was performed, whether by downtown new music groups or at the Music Center. He was always surrounded by well-wishers and always had a story or 10 to tell about the past.

The final two concerts he attended were as recently as January to hear Tilson Thomas guest-conduct the L.A. Phil and to catch its Ellington celebration, which included “New World A-Comin’.” Huang says that she played a recording of the Ellington/Strayhorn “Take the A Train” for him in the hospital during his last hours.

William Kraft is survived by Joan Huang, his wife; his son, Patrick Kraft; daughter Jennifer Slawta; six grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.