Can LACMA afford its massive re-design? A look at the numbers

Michael Govan responds to critics who say building a new Peter Zumthor-designed complex will leave the museum swimming in debt. With demolition just weeks away, we look at LACMA’s tax forms and current debt load.

- Share via

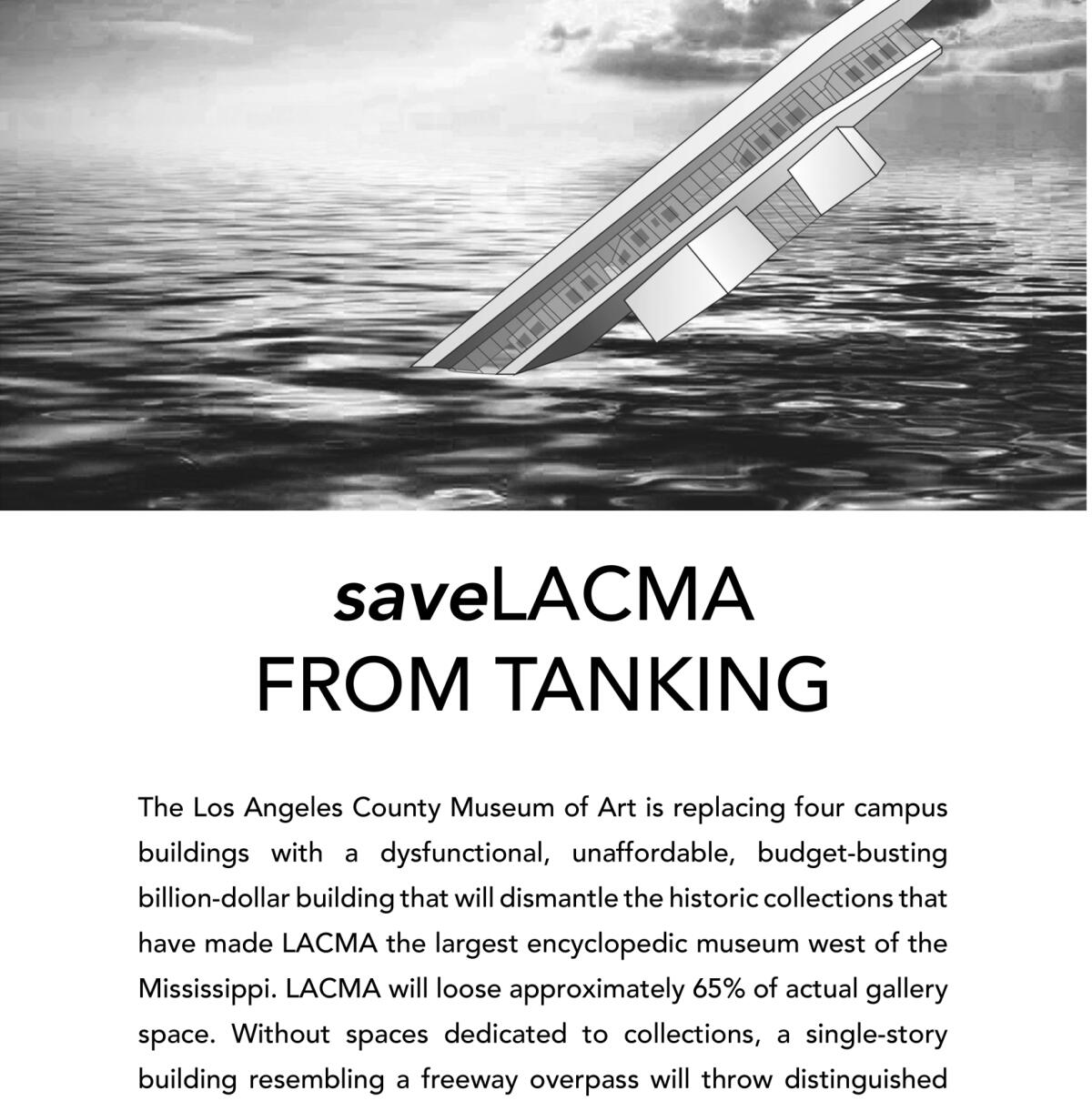

It was the mystery advertisement that got the L.A. art world buzzing. Late last month, a full-page ad appeared in the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times showing a rendering of architect Peter Zumthor’s design for the new Los Angeles County Museum of Art sinking like a rock into a shimmering sea.

“saveLACMA FROM TANKING,” blared the headline, accompanied by a critique of LACMA’s “budget-busting” design.

The ad — inspired by a famous 1970s photomontage by Chicago architect Stanley Tigerman — directed readers to a website with the address savelacma.org and was paid for by a group calling itself the Citizen’s Brigade to Save LACMA. That’s not to be mistaken for the nonprofit Save LACMA, a separate group, launched last summer with the website address ourlacma.org.

Confused? So was everyone else.

Save LACMA 1.0, led by nonprofit consultant Rob Hollman, denied responsibility for the ad via a Tweet: “It was written by an individual with his own personal agenda who is not related, in any way, to Save LACMA.”

A report in Hyperallergic indicated that L.A. architecture writer and curator Greg Goldin and New York-based critic Joseph Giovannini were behind Citizen’s Brigade. Giovannini has been highly critical of the LACMA project in the Los Angeles Review of Books over the years. And three days before the ad appeared, the pair had posted a video to YouTube in which they discussed what they viewed as the Zumthor plan’s many shortcomings.

Goldin acknowledged his involvement to The Times but stated, “The Citizen’s Brigade has no formal organization. It’s just to try to get the word out.” He declined to reveal who is funding the ads (there have been two others since the first appeared). “It’s completely anonymous.” (A Los Angeles Times spokesperson could only confirm that the ad was placed by the Citizen’s Brigade to Save LACMA.)

Giovannini, meanwhile, denied being part of the campaign, adding via telephone from New York, “It’s a red herring whether or not I’m involved,” though he does believe the building is “wrong for so many reasons.”

Hollman is frustrated by the confusion the ads unleashed but does see a bright side to this rather theatrical squabble. “P.T. Barnum once said there’s no such thing as bad publicity — I don’t necessarily agree with that,” he says. “But all of this has drawn a lot of attention to the issue of LACMA.”

Teardown on horizon

It’s been seven years since LACMA Director Michael Govan first revealed plans to raze four buildings on the museum’s campus — three from the 1960s by William L. Pereira & Associates and a 1980s addition by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer — and replace them with a single, sweeping design by the Pritzker Prize-winning Zumthor. Questions about the radical nature of the design — which includes an unorthodox plan for the building to straddle Wilshire Boulevard — and the project’s steep budget, have come up at every turn. Now they have hit a critical juncture. Last month, the museum began construction abatement to remove asbestos on the Pereira buildings; demolition is expected to begin by the end of March, despite the fact that no final plans for the future museum’s galleries have been publicly revealed.

“My concern,” says Hollman, “is that they will have this unfinished building, or they will finish it, and there will be this big bill to pay.”

Govan says these fears are wildly overblown. “The clear assumption is that we cannot go forward unless we can pay off the debt,” he tells The Times. “It’s a clear plan and it’s been reviewed by treasurers and the county and the [museum’s] finance committee.

“One of the things I need to hold as CEO is that the debt can be paid off without future fundraising so that my successors aren’t burdened by this project.”

Govan’s cause got a welcome jolt late last month when, after a months-long fundraising drought, LACMA announced a $50-million pledge from the W.M. Keck Foundation, whose chief executive, Robert A. Day, is a LACMA life trustee. The news came as the museum revised its $650-million estimate for the building project to $750 million (a number that had been used internally for at least a year).

Govan notes that the additions to the budget are not for construction but for related soft costs — including portable structures to house the education department and temporary bathrooms. He also says that coming up with another $100 million after raising nearly $650 million in private and public funds for the project “under enormous skepticism” is “like walking after you’ve run hard.”

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art will start demolition soon on its midcentury campus. In New York, MoMA partially proves the power of a different approach.

But even if he raises the funds without effort, there is still the question of the museum’s existing debt, and what it might mean to add even more.

According to the museum’s most recent 990 tax forms, filed in 2018, LACMA is carrying $331 million in county bond debt that was used to pay for construction of the Resnick Pavilion, the Broad Contemporary Art Museum, the Pritzker Parking Garage and other projects. In addition to that debt, the museum has $112 million in other liabilities, such as accounts payable and accrued expenses. This brings LACMA’s total debt to almost $443 million.

The Art Institute of Chicago, which has more than double LACMA’s assets (including an endowment of almost $1.1 billion), carries $298 million in total liabilities. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, an encyclopedic institution of comparable size and financial scale to LACMA, owes $243 million.

LACMA’s debt level is approaching that of the New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which recently undertook an expansion project by architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, adding more than 40,000 square feet of gallery space. MoMA owes about $479 million, according to 990s filed in 2018. The museum’s total assets, however, are worth $2.2 billion, and include an endowment of $1.1 billion. By comparison, LACMA’s total assets of $766 million (including a $139 million endowment) come to about a third of that.

Compare LACMA’s debt as a percentage of its total assets and the numbers grow starker. Debt for Chicago’s Art Institute stands at nearly 19% in comparison to its total assets; Boston’s MFA comes in at 20%. The Whitney Museum of American Art, which completed a new building in Manhattan by Renzo Piano in 2015, currently has a debt ratio of 13%. LACMA’s is nearly 58%.

Joanna Woronkowicz, a professor of nonprofit financial management at the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, says that number is high. “Normally you want to get below 40%,” she says. “But interpreting that in context is really important.”

And, certainly, LACMA’s unique context does require explanation.

Namely, this has to do with the museum’s financial arrangement with the County of Los Angeles. The museum receives a portion of its budget from county taxpayers in the form of an annual subsidy of about $25 million, adjusted for inflation. That’s not chump change; it amounts to 19% to 23% of the museum’s annual budget. (Over the last three tax periods on record, LACMA’s budget fluctuated between $108 million and $135 million per year.)

For the museum, the guaranteed county income is the equivalent of having an estimated $521 million in additional endowment money, on top of the $139 million that already sits in the endowment fund. (This is based on average nonprofit endowment returns of 4.8%, as published in a 2019 study by finance scholars at Georgetown and New York University.)

If you adjust LACMA’s numbers to account for this additional asset, the museum’s debt ratio drops to 34%.

But that number is still high in comparison with other arts institutions. The seven other museums I analyzed for this story, including the Art Institute, the MFA, the Whitney, MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Nelson-Atkins in Kansas City, Mo., collectively averaged a debt ratio of 17.5%. LACMA’s is practically double that.

This does not mean LACMA is in the red. In the 2018 fiscal year, in fact, the museum had more than enough net assets on hand ($323 million) to cover its short-term debts ($112 million) — a good measure of financial health, says Woronkowicz.

But the high debt ratio does raise a red flag on the issue of additional debt. And the Zumthor project could lard the museum’s ledgers with another $300 million in bond debt.

LACMA is no stranger to fiscal problems. In the early 1990s, it was forced to cut staff and programming when public funding and private donations cratered. And, in 2011, Moody’s Investors Service downgraded LACMA’s bond rating from A2 to A3, making it more difficult for the museum to borrow money at low interest rates. It has remained at A3 ever since — though in 2017, the most recent year for which a rating is available, Moody’s described the museum’s outlook as “stable.”

Govan says the funds to pay for the debt are “included in the master plan” and will be covered by the $640 million in construction pledges the museum has already secured.

Tony P. Ressler, the private equity businessman who serves as cochair of LACMA’s board, says that the museum’s existing debt has been taken into account — and that the board would have never opted to kick off construction if it didn’t have most of the building’s capital costs accounted for.

“What we have is an option to borrow $300 million from the county as we collect the $640 million,” Ressler explains. “We have two cochairs. We have an executive committee and we have a finance committee and we have 53 board members who have all been through the plan and the optionality. And it is our full intent to build the building successfully and retain our investment-grade status and not jeopardize the financial stability of the institution.”

But pledges can take time to roll in as patrons hang back to make sure that a given project is moving along to their liking.

The additional bond debt is therefore something that the museum is likely going to be taking on at some point this year — at least until all the various moguls cough up. Currently, of the $640 million in pledges LACMA has received, the museum has collected $271 million. Of that amount, $125 million came from Los Angeles County taxpayers — the bulk of it released after last April’s Board of Supervisors meeting, to which Govan showed up with Brad Pitt in tow.

For LACMA, the additional bond debt will be like paying off two mortgages at once.

Servicing the existing bond debt comes to about $14 million per year. The new bond debt, which LACMA will have to start paying off in 2021 (before the new building is finished), will come to another estimated $17 million annually. That’s some $31 million in debt payments — or more money than the county gives the museum every year.

Costs go up

While the county subsidies give LACMA financial breathing room that other institutions do not have — making it less dependent on fickle markets — the margin of error is slender. This could spell trouble for the institution if the building goes over budget, as major museum construction projects are wont to do.

A few days after a high-profile media preview of the Renzo Piano-designed Academy Museum of Motion Pictures next door to LACMA, it was quietly announced that the long-delayed movie museum, now set to open Dec. 14, is nearly $100 million over budget. “The museum is now projected to cost $482 million,” Variety reported. “That’s a 24% increase over $388 million, the budget figure the Academy has cited since 2015. The Academy is expected to launch a $100 million bond offering ... to cover the cost overruns.”

Woronkowicz has spent about a dozen years studying cultural capital projects. In 2012, she and a group of colleagues published a study through the University of Chicago’s Cultural Policy Center that examined every cultural building project in the U.S. from 1994 to 2008. The group found that museum projects, on average, went over budget by about 46%.

“It’s honestly maybe one or two in 10 projects that stay on budget,” she says. “Expenses creep up on these projects and all of a sudden your annual liabilities increase as well.”

Zumthor’s complicated building isn’t making things any easier.

For one, this is no ordinary, steel-frame and drywall construction. The design calls for a pair of massive, 347,500-square-foot, poured-in place concrete slabs that have to be engineered to bridge Wilshire Boulevard. The building also lies at the juncture of three seismic faults and the tar pits. In addition to normal environmental concerns, like climate, the design must take into account issues like methane mitigation. (For that, we can thank L.A.’s forefathers for having the terrific foresight to plant the city’s priceless objets next to bubbling tar.)

Already the issue of cost has affected the scale and nature of the project.

Last March, the new building shrank by more than 10%, or some 40,000 square feet from one iteration to the next, losing 11,000 square feet of gallery space in the process. This means that the new design will have less gallery space than is currently contained in the four buildings it is replacing.

As the design has evolved, some of the building’s most interesting facets have been pruned, such as the double-height chapel galleries, lit by clerestory windows, that would have provided a visual break from the pancake flatness of the building. Also edited out of the current iteration of the project are the solar panels, which would have made the building more energy-efficient.

The museum’s shrunken design was revealed last year not through public meetings but only when the final environmental impact report was put out a few weeks in advance of the Board of Supervisors meeting that released taxpayer funds for construction.

And now, six weeks before demolition is set to begin, the museum’s internal layout — one that purportedly will transform the ways in which permanent collections are displayed — is still a mystery. Govan says that construction drawings, the designs that literally guide the construction process, are now 50% complete and that gallery plans will not be available until next month (when, coincidentally, demolition begins).

Will the museum go over budget?

“I have a ton of oversight,” says Govan. “I have the county. I have an oversight committee. ... We wouldn’t be allowed to go forward if the building wasn’t on budget.”

“We take our budgets incredibly seriously and we take our [bond] rating very seriously,” says Ressler. “We take our construction projects incredibly seriously. If you look at Resnick or BCAM or the renovation of the Japanese pavilion, it’s all been on time and on budget.”

The projections, moving forward, Ressler says, take into account potential overages. “I should assure you that we have built in a cushion.”

He notes that the project represents significant private investment — ultimately, $525 million in private pledges to cover capital costs — in a building that will ultimately belong to the county.

“A building of this impact and notoriety and excitement, whether you love it or don’t love it, does inject an excitement in L.A. County for economic growth, for jobs, for tourism,” Ressler says. “To that, we would say, emphatically, yes.”

Those reassurances haven’t persuaded LACMA’s critics. “I think all of us who are concerned about the future of LACMA believe that the L.A. County Board of Supervisors needs to say, ‘Time out,’” says Goldin, of the Citizen’s Brigade. “We need to look at the money and what money needs to be spent on the building that they’re proposing.”

Hollman, at the rival Save LACMA, is at work on a ballot initiative that will propose limitations on how projects of this nature are executed, calling for a design review process and a requirement that LACMA include a county supervisor on its board.

“The Tar Pits, the Page Museum, they did the right thing,” says Hollman, of the announced plan to revamp the park and museum where the tar pits lie. “They opened it up to competition. They invited the public to comment on it. ... At LACMA, that never happened. Govan came to town with Zumthor on his mind.”

(Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, in whose district the museum resides, was unavailable for comment for this story.)

How the Zumthor building will take shape over the coming years and how it will affect LACMA’s finances remains unresolved. In addition to more debt, the museum could face extra maintenance and other costs as a result of the new infrastructure. (Already, LACMA is facing the additional expense of renting office space since the Zumthor building doesn’t have room for the staff.)

“The question is, what are the alternatives?” asks Woronkowicz. “Once these projects get started there often is no alternative. They keep going.

“Once the demolition is done, there is really no stopping,” she adds. “That’s when the costs really start to add up.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.