Czech history through the eyes of a filmmaker

- Share via

Czechoslovakia owes its unfortunate history to its lot as a main stage for the great conflicts of the 20th century. Born a democracy at the end of the First World War, it suffocated through decades of Nazi and Stalinist barbarism, with periodic flourishes of democratic revival.

An interview with Ivan Passer about his 1969 escape with Milos Forman from their homeland evolved into many hours of his reflections as a witness to much of that history — a storyteller’s account of its tragicomic absurdity and stubborn humanity.

WORLD WAR II

After wartime hardships separated Ivan from his parents, the boy lived with his grandfather Ervin, whom the Germans determined was Jewish enough to warrant action.

One lunchtime over alphabet soup, young Ivan was forming a word at the bottom of his bowl, “and I hear the sound of a heavy spoon hitting the plate,” he said. “I look up. Grandfather falls to the ground.” Having gotten wind that the Gestapo was closing in, Ervin had poisoned himself. He would survive, however — not only his suicide attempt, but, incredibly, five Nazi death camps — saved time and again by happenstance. His liberation came finally on a death march to Austria late in the war, when the German guards, spooked by the sound of Russian artillery in the east, abandoned the prisoners. Ervin made his way to his brother’s apartment in Prague, emaciated and in his prison garb. When his sister-in-law greeted him at the door, she said, “Ervin, is this how you walk around on the street? You look like a monkey.”

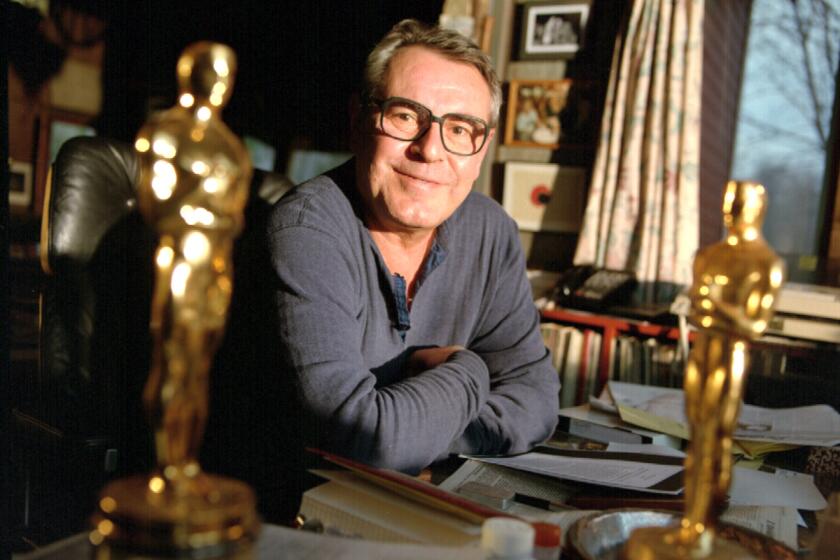

The friendship between Czech New Wave pioneers Milos Forman and Ivan Passer was crucial in the life of the man who directed ‘Amadeus’ and ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.’

Then there was Ivan’s uncle the spy. Max Passer was the No. 2 in an underground group that revealed to the British the secret production site of the Nazis’ V-1 rocket. The Brits bombarded it, and the Germans came for Max. He was arrested and injected with typhus, and died five days after the war’s end. But he would never be celebrated as the war hero he was, because, in the communist era to come, Max Passer — a successful lawyer who’d held important government posts since the Austro-Hungarian Empire — was denounced as a bourgeois, and therefore forgotten. “If not for Communists, he would have been a big hero, because he was. If I ever met any, that was him,” Passer says.

But Passer’s most indelible memory of wartime was witnessing its horror first-hand. On a day near the war’s end, he saw some young German soldiers who’d just been released from a hospital. “They were just kids — teenagers,” Passer said. “They had bandages all over.” A group of Russian soldiers confronted them, and executed them on the spot. “They mowed them down with machine guns. I still regret that I saw that.”

(The experience would become fundamental to Passer’s lifelong contempt for gratuitous violence in movies, a practice he condemns as “a dirty business” and “a sacrilege.”)

Still, Passer counts himself fortunate. Though separated from their parents during the war, he and his sister weren’t orphaned, as young Milos Forman was. “We got lucky because the war did not really affect our lives except that we had no father and no mother. But we had our government, which we were used to.”

AN EARLY DREAM OF ESCAPE

The communist coup of 1948 coincided with Forman and Passer’s time at the King George boarding school at Podebrady Castle. It was shortly thereafter when Ivan, along with a roommate, Josef Masin, began scheming to escape Czechoslovakia. “Already then,” Passer said. “We were 14 years old.”

The Elbe River runs right by the castle, and downstream was West Germany. So Ivan and Josef hit on a plan. “We were going to build a submarine,” Passer said.

The boys’ vessel was never realized, but the dream persisted. In 1953, Josef and brother Ctirad — sons of a Resistance hero killed by a Nazi firing squad — led a group of five on a quixotic armed escape. The Masin brothers’ impossible flight to the West, in which they outmaneuvered thousands of East German police and Soviet soldiers, is a story of national legend.

Like Passer, Josef Masin would make his way to California. He lives today in Santa Barbara, and he and his fellow emigre remain friends.

A LESSON IN AUTHORITY

After Ivan was kicked out of King George — one of eight times he was jettisoned in his school career — his father sent the unruly teen to the small city of Litvinov to live with the town judge and his family. “There I got my first political experience,” Passer said. “And it changed my life.”

Judge Prochazka, a classically educated man fond of reciting Latin poetry, heard cases of petty transgression and presided with equanimity. The rowdy drunks and bicycle thieves typically got a few days in jail, where the judge was known to visit the convicts for an evening game of cards. Ivan was fond of his host, whose courtroom proceedings the boy often attended, often alone.

One Sunday as a crowd mingled in the town square, a small explosive went off outside the local Communist Secretariat, damaging the front door. Party officials were clearly behind it, but they declared “anti-Communists” responsible and drew up a list of names. The mayor, a few teachers and others were handed sentences of 10 or 12 years’ hard labor. “For nothing,” Passer said. “They were innocent.”

The episode insulted Judge Prochazka’s sense of justice. He was in his fury one day as his son and Ivan left for school, “his face beet-red like a turkey,” Passer said. When the boys returned that afternoon, the judge was dead. Heart attack. “He couldn’t take it.”

Ivan was shaken. “I said to myself, I don’t want anything to do with these people for the rest of my life. And I never called anyone ‘comrade,’ I was never any part of any organization. Which was very, very difficult.”

THE NEW WAVE

As talented young artists with a seething contempt for their government, Forman and Passer found themselves in good company at the Prague Film Academy, the incubator of the Czech New Wave.

The academy had cultivated a carefully camouflaged subversive streak even through the harshest years of Stalinism. It offered its students a secret passageway to the history of cinema at a time when most movies from the outside world were officially forbidden.

The great filmmaker Milos Forman never spoke about his defection. In fact, he never called it a defection.

Passer recalls the words of A.M. Brousil, dean at the time, as he introduced class one day: “Ladies and gentlemen, I am going to show you movies you shouldn’t see. ... I want you to learn and analyze movies, and feel free to say what’s on your mind.

“And if anything of that should get out of this class, I am going to deny it.”

The atmosphere ignited the extraordinary pupils’ talents, and a cinematic movement.

The New Wave filmmakers of the 1960s demanded not only a new means of expression, but the right to express — their right as artists, and the right of all Czechoslovak people. The shared sense of moral conviction united them in a spirit of camaraderie.

“We were very fond of each other. We understood something, which I have never seen since” in all his decades in the movies, Passer said. “That success of one of us was opportunity for the other.”

The movement helped engender a period of cultural and political openness, culminating in the Prague Spring, ushered in by reform-minded leader Alexander Dubcek in 1968, who famously envisioned it as “socialism with a human face.”

To those who helped realize it, Prague Spring felt inevitable and inexorable. “You could say what you wanted without being afraid somebody would report you,” Passer said. “There was a battle of ideas. … It was a very exciting time for all the arts.”

It was a time of Vaclav Havel’s plays and Bohumil Hrabal’s fiction, but for Passer, the new cinema played a special role. “I believe ... that film as a medium has a peculiar capability to predict future,” he said.

He notes a parallel to Hungary, which had its own period of democratization snuffed out by a Soviet invasion, in 1956. “Like the Hungarian movies predicted the political situation, which led to Soviet invasion, Czech movies predicted Prague Spring, which led to Soviet invasion.”

THE SOVIET INVASION

After the Soviet bloc invasion of Czechoslovakia on Aug. 20-21, 1968, when 165,000 soldiers and 4,600 tanks poured over the borders, Czechs took to the streets in peaceful protest. They jeered their intruders, who were dumbstruck to find they were not welcomed as liberating comrades. Writer Milan Kundera, encapsulating the demonstrators’ momentary euphoria, proclaimed it “the most beautiful week that we have ever lived through.”

Meanwhile, protester casualties mounted. News came that Dubcek and his fellow reformers had been spirited off to Moscow, where they were drugged and forced to sign an agreement to rescind the Czech program of democratization.

No one knew whether the new mandate in Prague was a detour on a path back to liberty, or a dead end. “Every day was something happening, which was no good news,” Passer said.

Passer and Forman fled the country in the early hours of Jan. 10, 1969. Six days later, a 20-year-old university student, Jan Palach, immolated himself on Wenceslas Square in Prague to protest the Soviet occupation. He died on Jan. 19. His martyrdom briefly reignited the street protests, and he remained an inspiration to the Czech people through the dark years to come.

When speaking of the Soviet assault of August, Passer cannot contain his derision. “I despised the Russians so much I was not even surprised.”

That it was the Russians, who occupy a special place in Czech history and mythology as the original Slavic people, compounded the insult, Passer says.

“There used to be saying, going way back, that ‘the times are going to be best when Russian horses drink from the Moldau River in Prague.’

“But when they did, it was the worst.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.