Essential Arts: Chicano Moratorium route enters National Register of Historic Places

- Share via

It’s the weekend and we’ll be hate-watching “Selena” for the really bad wigs. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, a culture columnist at the Los Angeles Times, I’m here with the week’s essential arts news:

Chicano history recognized

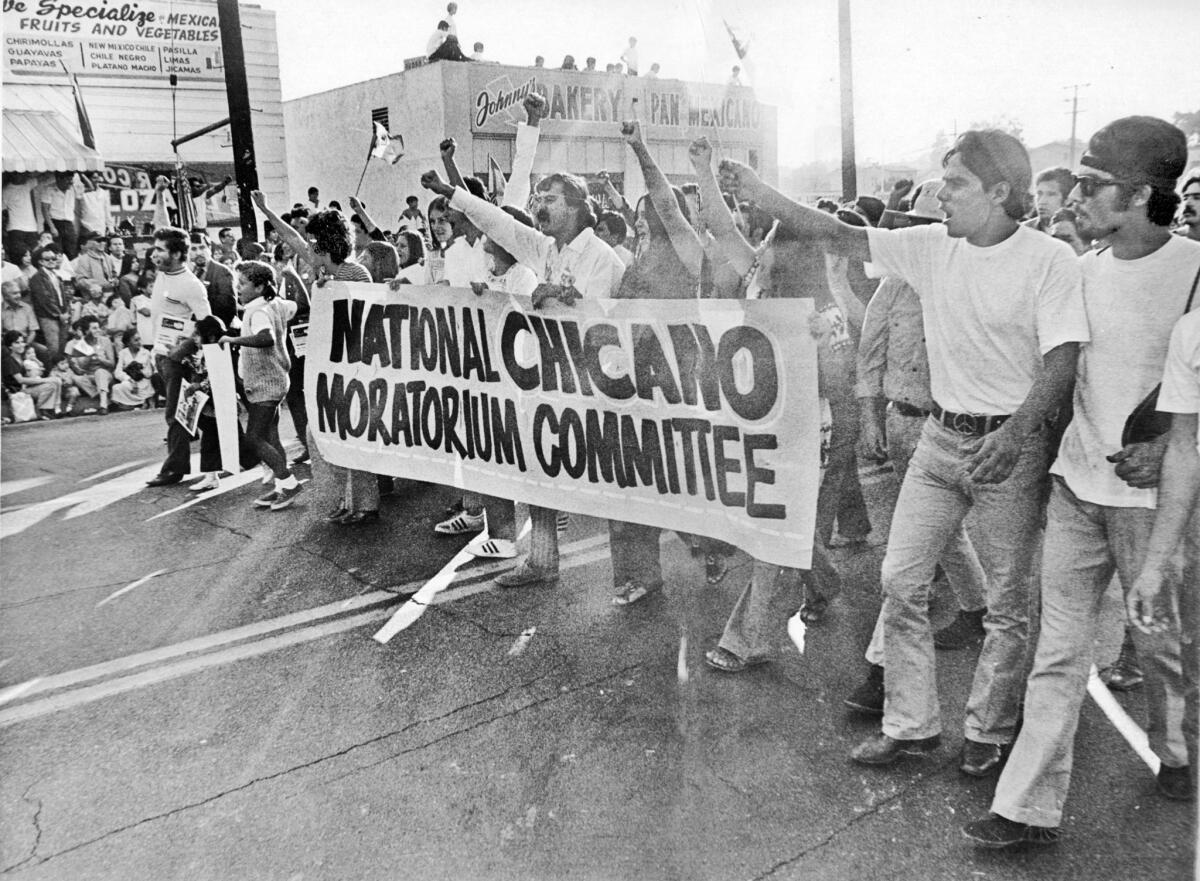

This year marked the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium, the massive East L.A. protest against the Vietnam War that ended in violence at the hands of sheriff’s deputies — and ultimately resulted in the deaths of three people, including Times columnist and KMEX news director Ruben Salazar, who was shot in the head with a tear gas projectile.

The anniversary was an important one. It landed in a year indelibly shaped by Black Lives Matter protests and conversations about systemic racism and police brutality — conversations that are just as relevant now as they were then. It was also an opportunity to retell the story of a decisive moment in Los Angeles, one that shaped its art and its culture, and to make present a piece of Chicano history that had never really saturated the broader public consciousness.

Now that history has gotten some official acknowledgment: the 1970 protest route — which ran from Belvedere Park to Laguna Park (since renamed Salazar Park), traveling south along Arizona Avenue, then west on Whittier Boulevard — was listed on the National Register of Historic Places last month. Also included on the list was the route of an earlier anti-Vietnam War moratorium, held in December 1969, which kicked off from the Five Points Memorial in Boyle Heights (at the northeast corner of Evergreen Cemetery) and then traveled east along Michigan Avenue to Obregon Park.

“The history of BIPOC communities are largely underrepresented in the National Register,” says M. Rosalind Sagara, who worked on the nomination on behalf of the Los Angeles Conservancy. “And that is something that we are mindful of and try to submit nominations that tell the full story of U.S. history.”

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The designation is part of a growing commemoration of sites connected with important civil rights happenings. The Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail in Alabama, for example, commemorates the route of the 1965 Voting Rights March.

For the purpose of the moratorium’s designation, two important locations linked with the march are also included: the site of the El Barrio Free Clinic on Whittier Boulevard (now Mission Furniture Mfg.), which served as the site of an important organizing and community service initiative launched by the Brown Beret activists in the late 1960s, as well as the Silver Dollar Café (now the Sounds of Music record store), where Salazar was killed.

The listing on the National Register of Historic Places won’t result in any immediate changes to the moratorium routes, which include residential and commercial corridors. (The designation doesn’t landmark these areas, merely designates them as sites worthy of preservation.) But Sagara says that now that the routes have been listed — a years-long process that began in 2015 — she hopes to engage L.A. County’s parks department in creating visual markers of some kind, because parks figure prominently in both moratorium routes.

The designations ultimately are a way of beginning to think about how this history might be showcased within the context of the L.A. landscape.

“It’s being able to mark that historic path, the ground that people marched, to highlight it, to uncover it,” says Sagara. “We want to recognize that these streets were important to the Chicano community.”

You can read The Times’ 50th anniversary coverage of the Chicano Moratorium at this link. And while you’re at it: pick up a copy of our special issue Chicano Moratorium zine.

About MoLAA’s deaccessions

Times art critic Christopher Knight reported last week that the Museum of Latin American Art had launched a highly unusual online auction: part fundraiser and part deaccession, featuring more than 50 objects from the museum’s own collection, including works by Roberto Matta, Rafael Coronel and Wifredo Lam.

This report was followed up by a story in the Long Beach Post on Monday in which MoLAA chief curator Gabriela Urtiaga explained that the rationale for the deaccession (the second such sale this year) was to diversify the collection. On a list of artists the museum said it wanted to add to its collection were Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Brazilian painter Tarsila do Amaral.

All of it raised the question of how a museum with a $3.7 million annual budget — and which ran a 2019 budget deficit of almost $341,000 — could afford such high-profile works. (Kahlo’s “Portrait of a Lady in White” went for a whopping $5.8 million in an auction at Christie’s last year.)

This week, Times culture reporter Deborah Vankin dug deeper into the sale, noting that it raised only $200,000 (less than half the high auction estimate of $474,000) and that the museum used a little-known e-commerce site for the deaccessions rather than go with an established auction house.

Urtiaga told Vankin that diversifying the collection, not financial troubles, were what motivated the deaccessions. “MoLAA has a responsibility in terms of representation of Latin American and Latinx art,” she said. However, among the deaccessions was a major, three-panel painting by the Mexican American neo-surrealist Ray Smith.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

A spokesperson for the museum acknowledged that MoLAA had faced deficits in the past but claims that the museum is now in the black. Vankin, however, catalogs a range of declining revenues as a result of the pandemic.

All of this makes an an interview with architect Enrique Norten that popped up in the Mexican publication Milenio on Friday especially mystifying. In it, the architect says that he’ll be designing an expansion for MoLAA that will include apartments, business and other services — which implies that some sort of major real estate development deal is afoot.

Asked about the report, a MoLAA spokesperson stated via email: “We are still in the negotiating phase. We will provide more details when the agreement is finalized.”

I expect there will be much more to come. Any expansion at this point rests on a mountain of what ifs — especially in the middle of a revenue-guzzling pandemic.

What’s certain is that if MoLAA slips back into deficits, or experiences some other financial calamity, it will be in a field where the number of institutions devoted to Latino art remains slim. On Thursday, Sen. Mike Lee of Utah blocked legislation to advance the creation of a National Museum of the American Latino in Washington, calling the concept divisive. “The so-called critical theory undergirding this movement,” he said, “does not celebrate diversity; it weaponizes diversity.”

MoLAA could be a counter to Lee’s ideas. Let’s hope it rises to the occasion.

Lost and found

This highly unusual year called for a different kind of year-end reflection, so we got to thinking about the ideas that have been lost and found during 2020.

Times theater critic Charles McNulty looks at how filmmakers are finding ever more artful ways to film theatrical works at a time in which we are unable to watch a live performance in theaters. “Nothing can replace the feeling of a group of strangers transforming over the course of a play or musical into a collective body known as an audience,” he writes. “But in this difficult pandemic year, directors have found ways of transmitting the power of an indestructible art form.”

McNulty also comes through with a list of 2020’s virtuoso performances. (You’ll have to click through to see who made it!)

In a year racked by social upheaval, classical music critic Mark Swed examines the state of our classical music institutions. He says that featuring a more diverse array of composers is important, but ground-up change is more so. He finds hope in the Youth Los Angeles Orchestra’s new Frank Gehry-renovated building currently under construction in Inglewood: “For real systemic change, we need a real system in place, something solid and lasting. YOLA is that system. It trains talent and attracts audiences. It goes to the core of the issue.”

He also has a list of the year’s top “classical music first responders,” who kept the art form mattering in 2020.

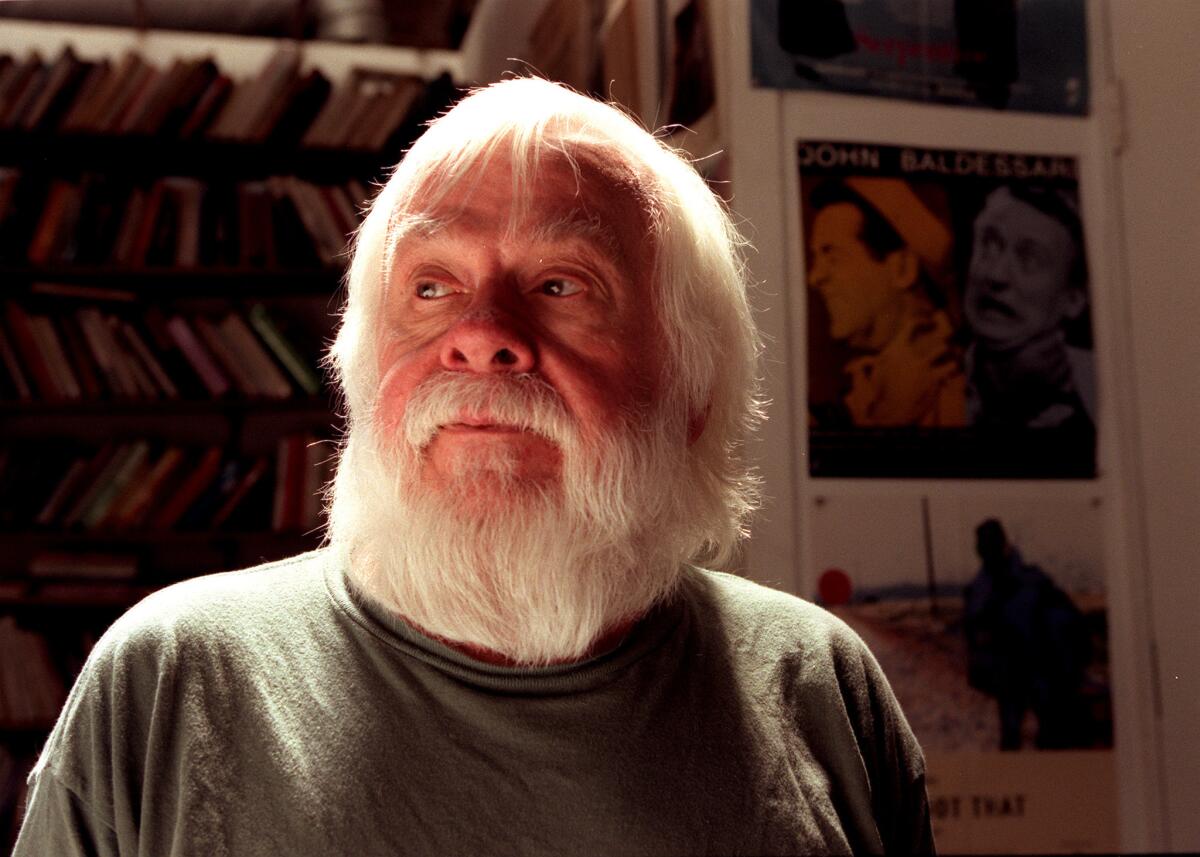

Art critic Christopher Knight wonders how an artist like conceptualist John Baldessari (who died in January) might have responded to 2020, a year in which “the months rolled by and the sorrows grew.” In a congenial end-of-year piece, Knight takes us down the rabbit hole of Baldessari’s erudite yet humorous thinking. “Wondering what Baldessari would do in the face of 2020’s relentless onslaught of brutalities might seem foolish or strange,” he writes, “but finally it’s comforting.”

The pandemic made it a bad year for museum shows, but there was one that stayed with me: “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945” at New York’s Whitney Museum. The exhibition meticulously unearthed the ways in which major American painters — Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, Jacob Lawrence, among others — were influenced by the Mexican mural movement. And as I note in the story, “there is perhaps no more satisfying sendoff to the xenophobia of the Trump era than an exhibition that rewrites American art history and, in the process, makes it more Mexican.”

Stepping back further, Daniel Hernandez writes about the COVID-19 pandemic as our first panhuman event and Mary McNamara asks how we will remember 2020 and all of its cultural signifiers, from Athleta face masks to the ring lights illuminating all those Zoom calls.

Plays and players

“Why take an 85-minute musical that is clearly based on the communal thrill of introducing children to live theater and turn it into a two-hour, constantly ad-interrupted television slog?” Culture critic Mary McNamara is not having NBC’s “Dr. Seuss’ The Grinch Musical!”

In the meantime, culture writer Ashley Lee digs into another television musical: “The Prom” on Netflix, which with a song-and-dance number titled “Love Thy Neighbor” asks evangelicals to love everyone — LGBTQ neighbors included. “I love that this song basically says you can’t cherry-pick what you believe of this religion, which is supposed to be rooted in kindness,” says director Ryan Murphy.

Coronavirus and the arts

The holiday season usually marks a money-making season for many performing arts organizations, which make a good portion of their revenue with stagings of “A Christmas Carol” or “The Nutcracker” ballet. Jessica Gelt and Makeda Easter take a look at how L.A.’s theaters and dance companies are weathering a year without holiday hits. “These shows deliver so many intangibles,” they write, “sowing company camaraderie, strengthening ties to core audiences and attracting new fans for the coming year.”

And, at a time when we could all use a little reconciliation, Mark Swed continues his series on deep listening, turning his attention to Brahms’ Piano Quintet in F Minor, Opus 34. “What is it about Brahms,” he asks, “that gives us permission to get along and thus makes him such a welcome counterbalancing icon for our contemptible, divisive culture?”

Plus, the New Yorker has an interesting look at how the New York City Ballet has faced the pandemic — by creating a video series that experiments with ways to create dance at a time in which dancers must remain socially distant.

Essential happenings

Need some holiday diversions for the family? Matt Cooper rounds up 17 IRL shows — including a drive-through Hanukkah experience and a drive-in adaptation of Puccini’s “La Boheme” by the Pacific Opera Project. A perfect lineup if you are going stir crazy at home.

For those planning to stay around the computer, Cooper also comes through with a whopping list of 81 streaming events, from a puppet show by the Bob Baker Marionette Theater to a burlesque “Nutcracker” organized by a troupe of Brooklyn dancers to a special Taylor Mac show made specifically for this pandemic holiday. (His vaudeville-style review is a benefit for UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance.) Sign me up!

Also, if you’re thinking ahead to New Year’s, Jessica Gelt reports that the Music Center will be hosting its eighth annual New Year’s party (typically staged in Grand Park) — it’s just that this year it will be streamed.

Passages

Puerto Rican artist Adál Maldonado, known simply as ADÁL, a figure known for his experimental plays on photography and a portrait series that documented Puerto Rican artists, has died at 72.

In other news

— A year of pandemic internet brain chronicled.

— Artist David Lew has sued L.A.’s Chinese American Museum after a city maintenance crew took down an installation he created and threw it out.

— LACMA is teaming up with Snapchat’s parent company, Snap Inc., to launch a project aimed at creating augmented reality monuments to be viewed on the app.

— The dispute over Zaha Hadid’s estate has been epic.

— A Vegas-style fountain designed by an L.A. studio has been proposed for a park in Dallas and architecture critic Mark Lamster describes it as “an unsustainable gusher of civic hubris.”

— A musical barge designed by Louis Kahn may have found a permanent home in Philadelphia.

— We are such a Death Star: Human-made materials now outweigh the Earth’s entire biomass.

And last but not least ...

Ham crystals and lettuce slippers. I want everything on this absolutely ridiculous gift guide.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.