Nick Cave on joy, grief and the ‘treasured evenings’ he spent in L.A.

- Share via

As a general rule, Nick Cave advises against “attaching a strict life narrative” to the records a musician puts out. Songwriters are storytellers, after all, and few have demonstrated more interest in ancient themes and dramas — justice, violence, sex, betrayal, redemption — than Cave has in the nearly half-century since he emerged from his native Australia, first with his band the Birthday Party and later with the Bad Seeds.

Yet Cave, 66, acknowledges that his work over the last few years “almost exactly” reflected the events of his real life — namely, the death of his 15-year-old son, Arthur, in an accidental fall from a cliff near the family’s home in Brighton, England, in 2015. Albums like the next year’s “Skeleton Tree” and especially 2019’s spectral “Ghosteen” “track a development through grief,” Cave says, “because that’s simply what happened to me.” In 2022, the singer lost a second son when 31-year-old Jethro was found dead of unspecified causes.

“Wild God,” Cave’s new album with the Bad Seeds, “has at its core a fundamental understanding of the suffering we go through as human beings,” he says. “But it’s also a joyful record”: a vibrant set of muscular and poetic rock songs that showcases the sympathetic interplay between Cave and his backing band (which here includes Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood).

Cave called from New York to discuss the LP, his attraction to church and the illusory promise of his own sex appeal.

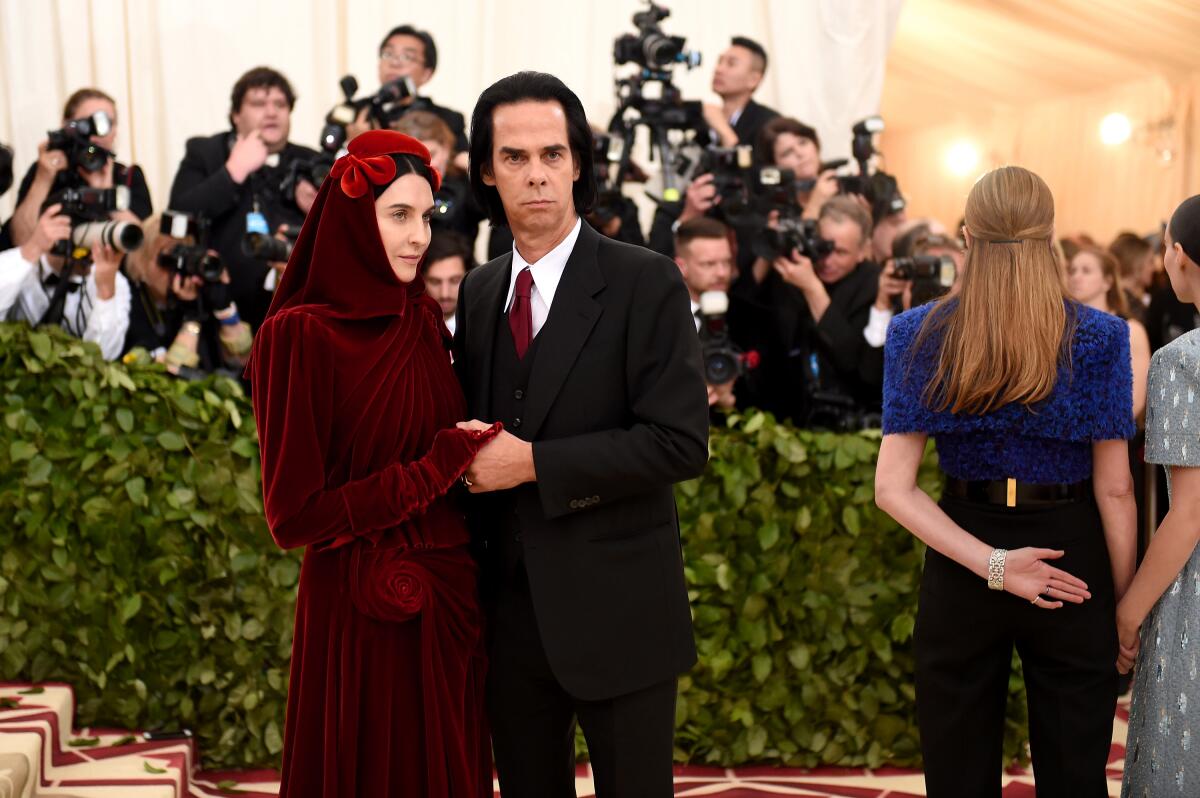

You and your wife, Susie, moved to Los Angeles from Brighton for a spell after your son Arthur died. I get the need for a change of environment. Why L.A.?

I’ve always loved America — it’s the country I love most of all, in a way. But for a long time I didn’t really understand L.A. I couldn’t work out the geography of it. Susie always loved it, so we’d holiday there, and eventually we just decided to get out of Brighton, where there was a lot of sadness for us, and go some place bright and full of sunshine.

Ahead of their Hollywood Bowl debut on Sunday night, Steve Lukather, David Paich and Joseph Williams of L.A.’s Toto look back at the band’s singular career.

Where in town did you land?

Up in the Hollywood Hills, a place off Outpost Drive. I had a very different sort of time living in L.A. for that period because I had a lot of creative friends all sort of anxious to hang out and exchange ideas. The sculptor and painter Thomas Houseago had a massive studio in Frogtown, and I used to just go there and hang around. And there were some actors and filmmakers — I won’t go into the whos — that we’d meet on a Saturday or Sunday night at different people’s houses to eat together and just talk about stuff. I really treasured those evenings.

Did spending time here shape your thinking about wealth or success?

I come from Australia, where you put your head up too high and it’s chopped off at the neck. There’s an aspirational aspect to L.A. that I rather liked. Maybe that’s because I’m a successful person. [Laughs]

You talk about finding joy in “Wild God.” Did pursuing that joy ever feel like a betrayal of your son?

That’s a huge trap that grieving people get into. I don’t buy it at all. I think when things like that happen to us — and it’s something that most of us will go through in one form or another — I think it’s imperative that we point ourselves towards the happiness that we can find, if only to influence the condition of those that have died. My greatest worry, as bizarre as this may sound, was my concern about my son, wherever he may be — the feeling he may have for how much pain his death caused his parents and other members of the family. So I felt on some level that it’s for him that we searched for some way of dealing with the world that had meaning and joy in it.

I spoke recently to Jack Antonoff, who told me that the latest record by his band Bleachers is the first that’s not in some way about losing his younger sister when he was a kid. For years he believed that anything that went wrong in his life was somehow connected to that tragedy. Does that make sense to you?

It makes sense, but I don’t see things the same way. Terrible things don’t really happen to you after you’ve lost a child. You can lose another child — that’s the terrible thing. But essentially the world has done its worst. I’ve seen it with my wife. She had this company, the Vampire’s Wife, that made extremely beautiful dresses that really grew out of her despair [over Arthur’s death]. And this company collapsed a few months ago. Now, this should affect Susie terribly, but on some level she’s kind of immune. We’re just toughened by grief.

Are you tougher than you ever thought you’d be?

I’d say toughened — slightly different than tough.

It’s clear how losing children affected your work. Did having children change it?

Yes. The idea of childhood is a thread that runs through a lot of my songs — from songs about our inability to protect our children, like “O Children,” to something like “Papa Won’t Leave You, Henry,” which was written as I cradled my newborn son and rocked him to sleep. These are the monumental things that expand the potential of the heart.

The polished R&B crooner and the elusive indie-folk auteur joined forces to create Legend’s new album, ‘My Favorite Dream.’

In addition to the Bad Seeds’ playing, the new album has quite a bit of choral singing.

I spend a certain amount of time in church, and part of the reason is because the music is so extraordinary. Church music, plainsong music, large choirs — all of that stuff is extremely beautiful, and I wanted to try and get some of that in this record.

Rock musicians use the term “gospel choir” pretty indiscriminately. Is that how you’d describe the singers in the song “Frogs”?

I was actually trying to get the choir in that particular song to sing as white as possible, even though there were like 20 Black people, because I wanted to have a sort of celestial, high-church feel — whereas something like “Conversion” is much more Black gospel. But I didn’t want to hire two choirs. [Laughs] There’s a sort of uneasy relationship between gospel music and rock music that I actually don’t really like. It can be really corny. So the way we went about recording “Conversion” was to do a kind of call-and-response thing that was completely chaotic and kind of out of tune, just to put a certain frenzy into the whole thing.

Do you find nourishment of some kind in church music?

Of course. It’s actually doing something to your spirit to listen to that stuff. But I find great solace going to church for all sorts of reasons, not just the music. It’s probably one of the only places remaining to us where we can take our various sorrows and feel them fully and safely.

At the end of “Frogs,” the narrator describes an encounter with Kris Kristofferson on a Sunday morning, which obviously calls to mind his “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down.”

It’s one of the great songs of spiritual disillusionment. “Frogs” is sort of bookended by examples of spiritual collapse, with the murder of Cain and Abel at the beginning and the Kristofferson song at the end.

I assume you’ve loved “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” for decades.

Yeah, I listened to a lot of country music as a kid growing up in Australia. It’s funny — I had no idea what was going on in the rest of the world, but from the age of 10 or so I’d sit and watch “The Johnny Cash Show,” which was screened on Australian TV on Saturdays. He was one of the musicians that I got really attached to in that obsessive way you do when you’re young because I saw him as being kind of an outlaw — kind of evil.

Cash did a great “Sunday Mornin’.” Willie Nelson too.

He’s got an extraordinary voice, Willie — he can make any song his own. There’s an amazing version of “The Scientist” by Coldplay he does that’s like the most beautiful thing you’ve ever heard.

Festival founder Phil Pirrone said the sudden cancellation of the event headlined by Jack White was largely due to economic reasons.

You specify on the new album’s lyric sheet that “O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is)” is for Anita Lane, the early Bad Seeds member who died in 2021. Did you set out to write a song about her?

No, I don’t think so. I sort of stumbled on some lines, and there was a joy to the whole thing that reminded me of Anita, so I kind of wrote into that. As I was writing on the piano, my wife came past: “Oh, what a lovely song. Who’s that about?” And I’m like, “Not you this time, babe.” In the art and music scene in Melbourne, Anita was this bright, shining, flaming, laughing creature that we dark, drug-addicted men sort of circled around. That’s what I wanted to capture in some way: the simple joy of what it was to be in Anita’s orbit.

The opening lines say, “She rises in advance of her panties / I can confirm that God actually exists.”

Not bad.

Would Anita have appreciated that imagery?

She would have liked that. But, look, everyone loves a song to be written about them. I wrote a song called “Scum” about a journalist once — terribly personal song about his private life and all the rest of it. He claims to this day that it’s his favorite song.

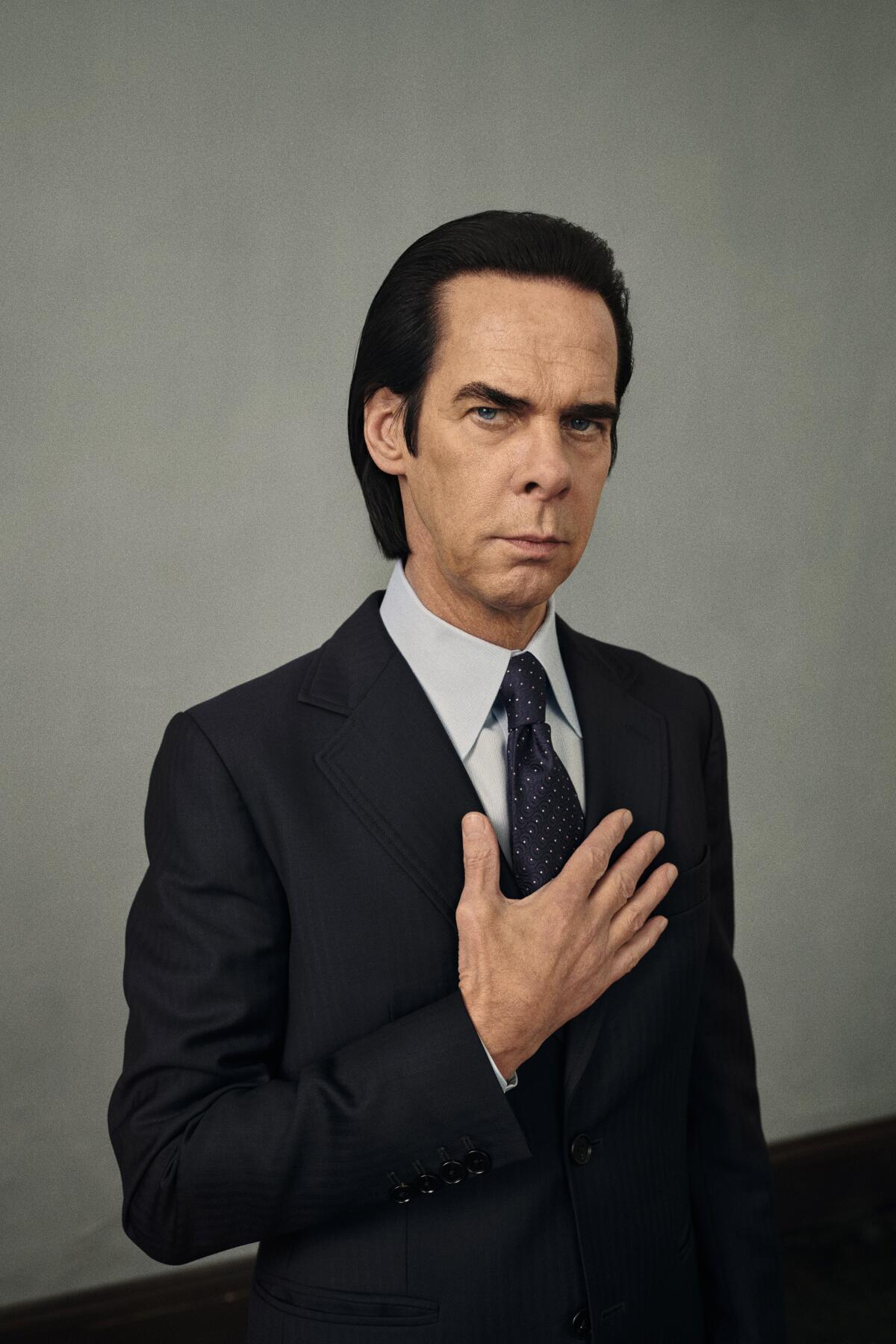

How crucial would you say your look is to your art? Would it work the same way —

If I was a balding, fat guy in cargo shorts? I don’t know. I’m not gonna mention any people — that would just be mean — but there’s a lot of people like that who are awesome.

Right, but what does sex appeal buy you as a performer?

Are you trying to say that if I wasn’t tall and thin and had some hair, I wouldn’t be able to get away with some of the s— that I get away with? That it’s a form of privilege? I don’t actually feel that way. I have all sorts of weird neuroses about my looks.

Is that true?

Ask my wife about it.

What’s the funniest song you’ve ever written?

This is a hard question, not because there’s hardly any but because there’s so many. It’s one of the mystifying things — that much like Leonard Cohen, my songs are cast as being depressive when a lot of them are written explicitly as comic songs. I don’t know if “No P— Blues” is the funniest song I’ve written, but it’s pretty funny.

You’ve spoken about how much it meant to you that Johnny Cash covered “The Mercy Seat.” Have you thought about who else you’d love to hear sing one of your songs?

A lot of people cover my songs, and some speak to me because these were the people that I listened to as a child. So for Johnny Cash to do it and to meet him and sing with him — that was a gift that can’t be taken away. But I don’t sit around and think, “I hope Taylor Swift does a cover version of my song.” Although, hey, I wouldn’t mind that. I’ve just put that out into the universe. Maybe it’ll manifest in some way.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.