What a Doob believes: How the Doobie Brothers survived ‘50-ish’ years to finally get their due

- Share via

When it finally happened last summer, the Doobie Brothers’ long-anticipated reunion with Michael McDonald took just more than a week to run into trouble.

Nine days after they kicked off a tour marking the California group’s 50th anniversary — a year late due to a pandemic-forced delay in 2020 — McDonald tested positive for the coronavirus and had to pull out of a performance at the Minnesota State Fair with just hours until showtime.

“The mistake I made was thinking I could go out to eat once in a while,” recalled the white-haired crooner, whose bandmates went ahead without him that night before calling off a handful of subsequent gigs while they waited for McDonald to recover.

So you could understand why the once-freewheeling Doobies, all vaxxed and boosted and in their early 70s, were running a pretty tight ship the other day at a North Hollywood rehearsal studio as they prepared to hit the road again — first for a two-week Las Vegas residency set to open Friday at Planet Hollywood, then for the remaining 42 dates of the anniversary tour, the group’s first official outing with McDonald since the mid-1990s. Signs taped to the walls ordered any non-Doobie to wear a mask at all times; a burly crew member was quick to deliver the message aloud to anyone who appeared to need reminding.

Do these safety measures threaten to kill the fun of touring, at least as compared to the group’s ‘70s heyday, when the musicians traveled in a bar-equipped plane called the DoobieLiner? “Yes,” guitarist Pat Simmons replied immediately. (Once they start playing concerts this month, the bubble will tighten further, according to their manager, with no guests allowed backstage.) Asked how they plan to amuse themselves, Simmons deadpanned: “DoorDash.”

“But you just have to deal with reality,” the guitarist continued. “It ain’t perfect. Who cares? We’re here, you know? So f— it.”

“That’s a good phrase,” Tom Johnston, who splits lead vocals with McDonald, told Simmons with a laugh. “I like that. Covers everything.”

Even with a COVID-19 compliance officer on staff, the Vegas gig and the tour will serve as something of a victory lap for the Doobie Brothers two years after they were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. The band, which Simmons and Johnston formed in San Jose in 1970 — and which went on to score era-defining hits such as “Listen to the Music,” “China Grove,” “Black Water,” “Takin’ It to the Streets” and “What a Fool Believes” — had been eligible for induction for decades to no avail.

But if the Doobies were once viewed as lightweights by rock critics, their perception has warmed more recently thanks to the embrace of admirers as varied as Luke Bryan, who toasted the band during the Rock Hall ceremony, and Solange, who’s covered “What a Fool Believes” in concert. The Gen X and millennial fascination with so-called yacht rock — the genre coinage used to describe the cohort of acts spinning out mellow yet sophisticated soft-rock vibes in the late ’70s and early ’80s — helped the band’s chances, as did the fact that another of the hall’s 2020 inductees was veteran music manager Irving Azoff, whose powerful Full Stop firm took over the Doobies’ affairs in 2015. Said Karim Karmi, who manages the group with Azoff: “You have to have champions on the committee [that handles nominations], and you have to tell a story besides ‘They have hit songs and they tour a lot.’”

“We used to think the whole thing was bull—,” Simmons said of the organization’s notoriously political selection process. “Until we got in.”

Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Bob Dylan Center opened to the public this week, throwing into focus a towering cultural figure and a city wrestling with its past.

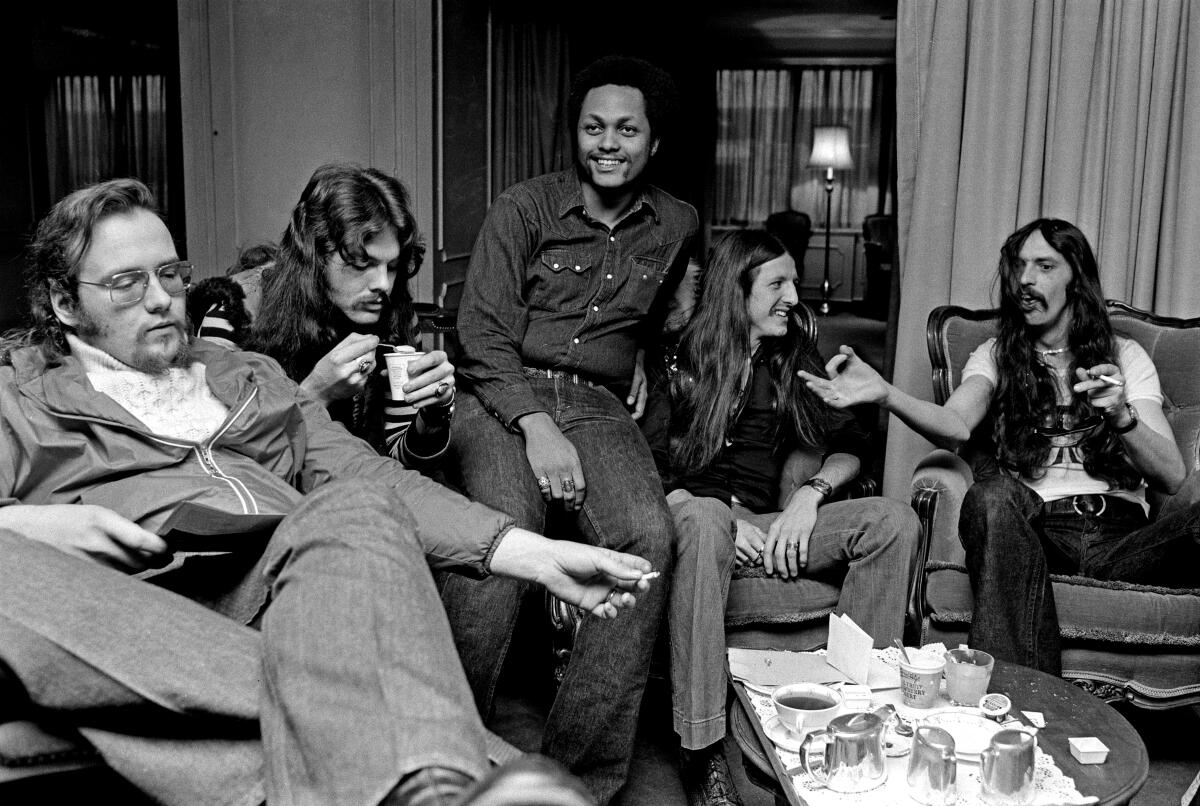

Now that they have, they’re taking full advantage of the recognition. In October, the band released a new studio album, “Liberté,” and this week Johnston and Simmons published a memoir, “Long Train Runnin’: Our Story of the Doobie Brothers,” which includes input from former bassist Tiran Porter, one of the relatively few Black men in the mostly white ’70s rock business, and the band’s longtime producer, Ted Templeman. With McDonald on board, the group is using its current live set — which also features guitarist John McFee, a Doobie since the late ’70s — to showcase the breadth of its catalog.

And what a crazily broad catalog it is, with hard-riffing biker-bar rock alongside fingerpicked acoustic blues and swank, jazz-inflected R&B. The easy way to look at the band’s initial run, which yielded 16 Top 40 hits, is to split it into halves: the early years when the growly-voiced Johnston was fronting the band and the later years when the smoothly soulful McDonald had the job.

“Kind of like Fleetwood Mac,” Simmons pointed out, invoking another classic-rock act with distinct eras (in Fleetwood Mac’s case, before and after Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham joined).

But the truth is that the Doobie Brothers — whose multiracial lineup reflected, and fueled, the diversity of their deeply American music — were always evolving, even when the singer stayed the same.

“We just kept trying things,” Johnston said during a break from rehearsal. Dressed in an array of dad jeans and sensible sneakers (except for McDonald, who wore flip-flops), the core Doobies had convened near the Burbank airport from their homes scattered around the West — Johnston in Marin County, McDonald and McFee in Santa Barbara, Simmons on Maui. Yet as they recounted the old days, they joked around like the lifelong pals they are. “Went from the first album, which didn’t sell s—, to the second album, which had a song that got on the radio — couple of them, actually,” Johnston continued. “Then the third album, we started trying synthesizer stuff. Album after that, we had the Memphis Horns.

“We’ve had a lot of players too. I mean this in the most respectful way, but we’ve had an exploding drummer problem,” Johnston said, referring to the “Spinal Tap” gag. “And bass players, we’ve had a few of those. They all brought something of their own to the music.”

The Doobies grew out of the Bay Area biker scene at the Chateau Liberté, a rough-and-tumble roadhouse in the Santa Cruz Mountains with a loyal clientele of Hells Angels. “It was the real deal — guys with guns taking big slugs from bottles of Jack,” said Templeman, who remembered heading up from Los Angeles to check out the band after plucking its demo from the slush pile at Warner Bros. Records. “But when Pat and Tommy would sing together, it was so beautiful. Kind of incongruous.” According to Templeman, the group asked for $20,000 to sign to Warner: “10 for equipment and 10 for cocaine,” the producer said.

The Doobies’ self-titled debut came out in 1971 and was quickly followed by 1972’s “Toulouse Street,” which went platinum, and 1973’s “The Captain and Me,” which went double-platinum. In 1975, the group topped Billboard’s Hot 100 with the folky “Black Water.” But as their success grew, Johnston’s health was deteriorating as a result of a bleeding ulcer; forced to bail mid-tour, the singer was replaced on the road by McDonald on the recommendation of guitarist Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, who’d played with McDonald in Steely Dan before Baxter joined the Doobies.

“The second I heard him open up his mouth, I said, ‘holy s—,’” Porter writes of McDonald in “Long Train Runnin’.” “My mind was blown right there.”

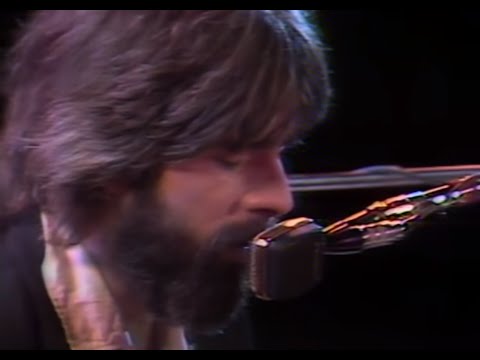

McDonald stuck around and began contributing to the band’s albums beginning with “Takin’ It to the Streets” in 1976; by the next year’s “Livin’ on the Fault Line,” the Doobies’ sound had changed dramatically to suit his nimble keyboard playing and quiet-storm vocal approach. Johnston insists today that he didn’t resent the shift. “But I didn’t feel like I was adding enough to the band at that point,” he said. “I wasn’t comfortable.” So he quit.

Kenny Loggins, who’d known the Doobie Brothers since they opened for Loggins & Messina in the early ’70s, recalls picking up on “the tension” in the group at that time. “Tommy and Michael, their styles were just so different. But Michael seemed like a breath of fresh air for the Doobies. Had they only had the Tommy Johnston era — and I love Tommy — they might not have lasted as long as they did. With Michael, they rode the tide of change in pop music.”

For the band’s next LP, 1978’s yacht-rock touchstone “Minute by Minute,” McDonald and Loggins co-wrote the silky and syncopated “What a Fool Believes,” which went on to hit No. 1 and won Grammy Awards for record of the year and song of the year. “And we were up against ‘After the Love Has Gone,’” Loggins noted with pride, referring to the lush R&B ballad by Earth Wind & Fire. Over the years, “Fool” has been covered by Aretha Franklin, George Michael — even Kanye West’s Sunday Service choir, which transformed the song into a gospel devotional.

“Wasn’t it used recently on — whatever the hell it is — ‘Euphoria’?” Johnston asked his bandmates, and indeed the HBO teensploitation drama licensed the song for a scene in an episode from Season 2.

In spite of “Fool’s” commercial gains, the Doobies lasted only one more album before breaking up in 1982. They got back together sporadically over the next decade for charity gigs; Johnston and Simmons later organized a more formal reunion (minus McDonald, who’d started a successful solo career) and have been touring steadily ever since. Still, playing with McDonald again, Johnston said, “lifts it up a little bit — makes it more special.”

Pete Townshend on writing for Roger Daltrey (“not easy”); losing Keith Moon and John Entwistle; and his new Audible Original, ‘Somebody Saved Me.’

It’s also, not unlike that “Euphoria” sync, a good way to “keep the band’s brand alive,” as Karmi put it, in an age when record sales have all but vanished and a stream on Spotify pays a fraction of a cent. Asked whether they keep up with modern music, Johnston said, “I’m told by people that work in it that it’s disposable. They’re not songs you’re gonna hear 15 or 20 years down the line.”

“I disagree,” Simmons said. “I think there are songs as meaningful to young people’s lives as Steely Dan or Jefferson Airplane was to people our age. There’s a whole generation that’s gonna remember Snoop Dogg’s stuff forever.

“I mean, I can’t name one record of his,” he added. “But I appreciate who he is.”

As for their upcoming residency, nobody in the Doobie Brothers would describe himself as a huge Vegas fan. But after two years mostly spent sitting around — “We’re now calling it the 50-ish anniversary,” McFee said — they’re just happy to be performing again.

“When the pandemic started, I remember thinking I was gonna do all the things I never had time to do,” McDonald said. “Then I started watching HGTV and eating cookies.”

All of the Doobies are married and have grown children they thanked by name in their Rock Hall acceptance speeches. Do they expect their kids to come out and see the band on tour?

“Eh,” Simmons answered noncommittally. “They liked us more when they were younger.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.