Imagination, razor blades and ganja: How Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry changed the sound of popular music

- Share via

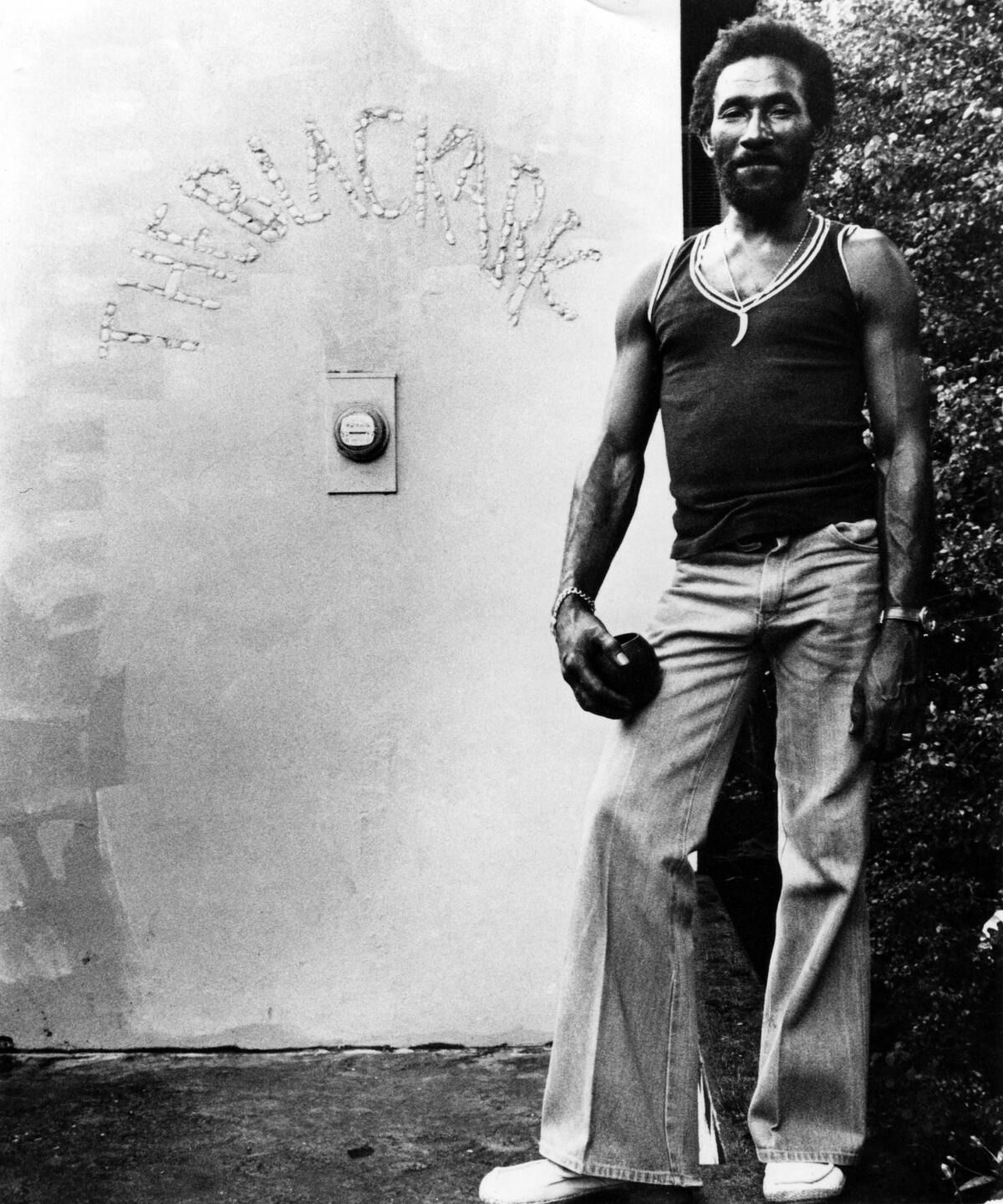

Asked about the revolutionary rhythms and songs created at his Black Ark studios in Kingston, Jamaica, reggae producer, dub innovator and studio icon Lee “Scratch” Perry described a cosmic process occurring deep within his early four-track studio tape recorder.

Although the machine afforded only use of four tracks during production, “I was picking up 20 from the extraterrestrial squad,” he said, adding matter-of-factly, “I am the dub shepherd.”

With his colorfully dyed hair, jangly jewelry, bedazzled hats and neon outfits, Perry, who died Sunday in Lucea, Jamaica, at age 85, presented himself as an eccentric island mystic. The sounds he shepherded across a lifetime behind the mixing board, though, were sophisticated and driven by a laser-like intent that helped change the course of popular music.

Although half a decade prior, George Martin and the Beatles had made grand, studio-built experiments in world-class rooms, Perry in the early 1970s constructed technological workarounds that multiplied the potential at a fraction of the price. Listing his many influential productions for Max Romeo, the Congos, Augustus Pablo, the Meditations and hundreds more might help quantify his contributions, but Perry’s influence extends far beyond reggae and dub.

Among the most innovative producers of the analog recording era, Perry built a ragtag four-track studio centered on a TEAC reel-to-reel, a Soundcraft mixing board, an Echoplex delay box and a Mu-Tron phaser. Seemingly duct-taped together, his gear generated stoned-immaculate sounds and ideas that served as the building blocks of remix culture.

“Rhyming live over records. Subtracting elements from a ‘completed’ song to make a ghostly new one. Studio engineer as creative artist. DJing as performance. Sound-system operators as hero-librarian-curators. It all sprang from Kingston, Jamaica,” electronic music producer and essayist Jace Clayton, who performs as DJ/rupture, wrote in his book “Uproot: Travels in 21st-Century Music and Digital Culture.”

Clayton described Perry and fellow Jamaican dub producer King Tubby as the scene’s “Plato and Socrates, laying down the foundations of contemporary electronic music culture.”

Painter Jean-Michel Basquiat cited Perry’s aesthetic as an inspiration, and his music has been featured in movies including “The Brother From Another Planet,” “Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels,” “The Royal Tenenbaums” and, most recently, director Steve McQueen’s reggae-soundtracked anthology series “Small Axe.”

A new Beach Boys box set with expanded versions of two overlooked 1970s albums, ‘Surf’s Up’ and ‘Sunflower,’ makes a strong case for their post-peak greatness.

As news spread of Perry’s death, musicians shared remembrances on social media. Describing “his pioneering spirit and work,” the Beastie Boys’ Mike D and Adam Horovitz wrote that they were “truly grateful to have been inspired by and collaborated with this true legend.”

Steve Albini, who produced the Pixies’ “Surfer Rosa” and Nirvana’s “In Utero,” said Perry’s “records... became talismans for anybody who ever tried to manifest the sound in their head.”

Perry, born Rainford Hugh Perry on March 20, 1936, produced and co-wrote the Bob Marley classic “Punky Reggae Party,” and produced early Marley and Wailers jams including “Keep on Moving,” “Duppy Conqueror” and “Mr. Brown,” as well as the entirety of the Wailers’ 1970 album “Soul Rebels.”

The Perry-produced Junior Murvin hit “Police and Thieves,” a sweetly sung indictment of gangland wars and police brutality, earned Perry popularity among the “punky reggae” crowd when the Clash recorded a version for its debut album. The band invited Perry to produce songs including “Pressure Drop” and “Complete Control.” In 2013, Perry entered the consciousness of a new generation when he was a featured in the video game Grand Theft Auto V as a DJ on a dub and reggae radio station called “The Blue Ark.”

On the 1998 Beastie Boys’ song “Dr. Lee, PhD,” Perry — who at various points nicknamed himself Little, King, Scratch, the Upsetter, Pipecock Jackson, Super Ape, Ringo, Emmanuel, the Rockstone and Small Axe — toasted over a hazy, weed-fueled journey through reverberating organ, bass and drums. “They who want total control always lose control / Some always lose their soul for silver and gold,” Perry shouted in rhythm during the track.

His guiding philosophy, Perry said, involved creating what he called “music that can make wrongs right” by “getting help from God, through space, through the sky, through the firmament, through the earth, through the wind, through the fire.” Organized sound, for Perry, had to be “like a living thing,” and the recorder (“the machine”) “must be alive and intelligent. Then I put my mind into the machine by sending it through the controls and the knobs.”

As a young laborer, Perry took a job clearing rocks for a construction project. Soon, he explained in the liner notes to “Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry: Arkology,” a set that gathered his Black Ark recordings, “I started making positive connections with stones. By throwing stones to stones I start to hear sounds. When the stones clash, I hear like the thunder clash, and I hear the lightning flash, and I hear words, and I don’t know where the words [were] coming from.”

The voices guided him in the late 1950s to Kingston, where he landed a job with producer and Studio One owner Clement “Coxsone” Dodd. Perry was soon scouting for talent — and helping to discover the vocal trio the Maytals. After an unsatisfying stint working with producer Joe Gibbs, Perry formed Upsetter Records and released “People Funny Boy,” his first hit. He followed that with a run of joyful instrumental singles based on themes from spaghetti westerns and action films.

Construction of Black Ark was concluded in late 1973, and the studio quickly became a magnet for vocal groups and solo singers. Born of necessity — and lots and lots of marijuana — Perry’s pre-computer cut-and-paste technology involved razor blades, recording tape, a sharp ear for rhythmic intricacies, thin strips of adhesive ribbon to lock sections together and lots of tummy-rumbling bass. Within a few years, the sound Perry advanced would inspire international superstars including Stevie Wonder, the Rolling Stones and Paul Simon.

As roots reggae’s foremost producer, Perry, wrote essayist and musician David Toop, built “an imaginal chamber over which presided the electronic wizard, evangelist, gossip columnist and Dr. Frankenstein.” In doing so, the producer advanced the idea of remixing already-existing recordings through editing, reverb, electronic effects, reworked rhythm tracks and stuttering vocal edits to create hallucinogenic sound trips that seemed to hit your eardrums like wafts of sunlit ganja-smoke.

Perry used his system’s weaknesses to his advantage: over-saturating tapes with sound waves and manipulating the results; harnessing distortion and feedback for use as sound effects; reversing and slowing tape to transform voices into ghostly moans; feeding drums through electronic echo chambers to make them wobble and jerk. Perry’s 7-minute dub version of Max Romeo’s “Chase the Devil,” called “Disco Devil,” is a lesson in the ways in which repetition, subtraction and silence, combined with sonic accents and pew-pew space-gun noises, could reenergize songs designed for the easy roots-reggae sway transforming Jamaican dance floors in the 1970s.

That distinctive quality was foundational in a music scene where shops such as Rockers International and Randy’s Records promoted both releases and parties, selling new 45s daily from the dozens of labels trying to break their records on the sound-system scene in and around Kingston. The most exciting productions resonated not just in the former British colony of Jamaica but also in the expat community in London and the dense Jamaican population in New York City.

The competition for ears rewarded songs that stuck out, and Perry imbued his music with surprise tones, sonic witticisms and oddly reverbed vocals. As a way to cut costs, the B-sides of singles at the time often featured bass-heavy instrumental “versions” of the A-side.

That reverberating bass was the key to dub, the reggae subgenre that artists including Perry and, earlier, his friend King Tubby invented in the late 1960s. As writer Luke Ehrlich famously described the difference between reggae and dub in an early 1980s essay: “If reggae is Africa in the New World, dub is Africa on the moon.”

When, in 1973, Perry’s band the Upsetters teamed with King Tubby to release “Blackboard Jungle Dub,” the Upsetters became one of the first groups to issue an entire album of dub versions.

Until dub came along, a recording was finished when it was pressed onto a record. King Tubby and Perry advanced the notion that a recording is never really done, since it can be infinitely re-recorded, remixed and reinvigorated anew with each edit. Dub versions also enabled DJs to extend dance-floor enthusiasm well beyond the song’s three-minute mark. Armed with two turntables and 45s, DJs could blend and mix versions on the fly. That practice reverberated in America when the Jamaican-born DJ Kool Herc started doing the same with funk and disco breaks in the Bronx to create the foundations of hip-hop.

Perry was obsessed with making music that was fun, he said, so he giddily experimented in the studio. In the Congos’ ”Children Crying,” Perry slowed down a tape of a crying baby until it roared like a lion. Years before sample culture changed popular music, Perry’s uptempo groover “Station Underground News” found him splicing the recorded chorus of the Chi-Lites’ “(For God’s Sake) Give More Power to the People” directly into the tape to incorporate it into the song. Believing it affected the sound, Perry exhaled streams of ganja smoke onto his tape reels, or buried them in his garden for a few days. For Jah Lion’s “Hay Fever,” a rework of Peggy Lee’s “Fever,” Perry looped into the recording the sound of a squeaking door.

On “Cow Thief Skank,” he merged reel-to-reel tapes of two different rhythm tracks to create a third. To produce one curious percussion sound that he used across his career, Perry stood close to a studio microphone and popped his open mouth with his hand to make a racquet-hitting-ball sound — then used edits and loops of that tape in drum patterns.

And then there was “Heart of the Congos,” the spine-tingling 1977 studio album by vocal duo the Congos. Often cited as Perry’s greatest full-length production, it’s an exquisite work filled with sweetly soulful hymns to Jah. The album found Perry mixing synthetic drums with musicians including Sly Dunbar, Ernest Ranglin and Gregory Isaacs. Singers Cedric Myton and Roydel Johnson offered song that dwelled on questions of biblical proportions involving truth, justice, God and Rastafarian beliefs on the location for the Ark of the Covenant.

“Heart of the Congos” was recorded at Black Ark a few years before a fire of dubious origins destroyed the studio and everything within it. Before Black Ark went up in flames in 1979, an increasingly drunken and stoned Perry had affixed to studio walls cut-out images, artwork, circular 45 labels, headshots and photos of the late Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, upon which he had written countless words, symbols and phrases. As relayed in the “Arkology” liner notes, in the days leading up to the blaze, Perry crossed out every “A” and “E” on the wall; at one point, he was spotted carrying a hammer and walking backward around Kingston neighborhoods.

Though Perry was detained on suspicion of arson, he wasn’t charged. But minus a studio, Perry was an untethered presence. It didn’t help that his inheritors had adapted some of Perry’s innovations to create a new sound. Called dancehall, its rise in the early 1980s eclipsed his efforts in the decades that followed. His two “Megaton Dub” albums in the mid-1980s featured solid grooves, but they were no match for the synth-heavy new tracks by Yellowman, Sugar Minott and Frankie Paul.

Delta variant be damned, many of our favorite artists are either performing at star-studded festivals, headlining concerts or releasing new albums this fall.

In England, however, Perry’s influence started seeping into the variant of hip-hop being made in Bristol by Massive Attack, Tricky and Portishead. Called trip hop, the subgenre adopted and amplified Perry’s love of bass and echo. In Europe, minimal electronic producers such as Vladislav Delay, Stefan Betke and Basic Channel absorbed Perry’s vibe to create dub techno. By then, Perry had moved to England and commenced a series of collaborations with peers including Mad Professor, the Scientist and Dub Syndicate. For Perry and Mad Professor’s 2000 album “Techno Dub,” the two went fully digital to explore the depths within silicon chips.

Perry moved to Switzerland in 1989 and married Mireille Campbell-Rüegg soon after. He lived the rest of his life in Zurich, London and Kingston. A constant traveler, Perry was spotted in late 2019 in Highland Park, where he was visiting Stones Throw Records’ studio for a collaboration.

Endlessly creative, Perry popped into studios whenever he had the chance. According to the site Discogs, Perry produced more than 1,100 releases and wrote or co-wrote just as many. Perry issued 222 singles under various monikers and 93 studio albums, as well as 100 compilation packages.

“Rainford,” his final solo album, came out via Adrian Sherwood’s On-U Sound label in 2019, and closes with what sounds like a benediction. “Autobiography of the Upsetter” features Perry recalling in rhythm his birth, youth, upbringing and inspirations. “I am the upsetter,” he chants, well aware that his philosophy upset the status quo and forged new ways of creating and hearing sound. As the music fades, Perry continues for a few measures more: “I am the upsetter,” he repeats before concluding, “I am the black angel.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.