When will live music return? Kenny Chesney says fans are ‘horny for it’

- Share via

It’s been almost a year since one of music’s biggest live acts enjoyed a night in his natural habitat.

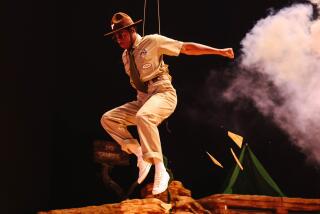

On May 25, 2019, Kenny Chesney played Tiger Stadium in Baton Rouge, La., to finish off his tour behind the previous summer’s “Songs for the Saints” album.

But that outdoor mega-concert — the kind the country singer is best known for — wasn’t actually his last show before the live-music business shut down two months ago as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

California is slowly reopening, providing hope that you might soon see your favorite artist in concert. But from an arena stage? A computer screen? A drive-in?

“I can’t believe I’m telling you this, but I did a wedding in Florida at the beginning of March,” said Chesney, ranked at No. 18 on Pollstar’s list of the top touring artists of the previous decade with ticket sales of more than $600 million. “And I don’t play weddings. But it was worth it,” he added with a laugh.

Because someone close to him was getting married? “Nope,” he replied. “Just somebody that really wanted me to play his daughter’s wedding.”

Now the memories (and the paycheck) from that private gig will have to sustain him for a while: In March, Chesney, 52, postponed the first set of dates on his latest tour, which had been set to open April 18 at the cavernous AT&T Stadium near Dallas; further dates, including a scheduled Aug. 1 stop at the new SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, are almost certain to be delayed as public officials and industry leaders figure out when it might be safe for tens of thousands of people to gather in one place.

“It’s one day at a time, trying to make plans,” said Chesney’s longtime concert promoter, Louis Messina. “My answer to everything is, ‘I don’t know.’”

The uncertainty hits especially hard for Chesney, whose muscular yet laidback music — think Jimmy Buffett meets Bruce Springsteen — has made his show an annual rite of summer for the devoted fans who call themselves the No Shoes Nation. This year an estimated 1.4 million of them were expected to see him play across 22 stadium concerts and an additional 18 gigs at amphitheaters throughout the U.S.; in 2018, Pollstar says, Chesney played 19 stadiums and 23 amphitheaters and grossed $114 million.

As a live draw, Messina puts the singer in “that superstar category” alongside the Rolling Stones and Taylor Swift (both of whom have called off all 2020 dates), and Chesney admits he’s found it difficult to roll with the cancellations given how accustomed his “body clock” is to being on the road this time of year.

“I feel a little lost, honestly,” he said the other day over the phone from his home in Tennessee, where he’s been “bouncing off the walls like everybody else” during quarantine. “A couple of Saturday nights ago I was supposed to play the Minnesota Vikings’ football stadium, and we didn’t go. So there’s just this empty place in our lives.”

Chesney got some brighter news this week when his latest album, “Here and Now,” debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200, giving him his ninth chart-topper — enough to tie with Garth Brooks as the country artist with the most No. 1s in the tally’s history. Chesney’s 19th studio disc overall, “Here and Now” — full of characteristic feel-good anthems as well as a romantic ballad co-written by Ed Sheeran — moved the sales-and-streams equivalent of 233,000 copies in its first week, according to Nielsen Music, edging out the latest project from the enormously popular rapper Drake.

Yet Chesney’s chart showing has also raised questions about so-called ticket bundling, in which fans receive a copy of an album as a bonus when they buy a concert ticket. Billboard allows albums delivered that way to count toward chart placement, as indeed happened with “Here and Now,” which was credited with selling 222,000 full-package CDs or downloads.

In this case, though, the strategy is complicated by the fact that many, if not all, of Chesney’s shows — the ones fans bought tickets for and therefore received copies of “Here and Now” — are likely to be postponed and may even be canceled.

“This fall is gonna say a lot,” he said. “I’ve got a lot of friends in the NFL, and I’m keeping my eyes on what they do, because it directly reflects what I do. But I’m confident we’re gonna play music somewhere. And if we get to, everybody’s gonna be — I don’t know what the word is — horny for it.”

From Drake to 5 Seconds of Summer to Kehlani, videos shot in quarantine have become a go-to medium to renegotiate the social contract of pop stardom.

Were you worried about putting out an album at this strange moment?

I went back and forth in my brain to see if this was an appropriate time. But whenever I’ve been in a funk personally, I’ve leaned on music to get me out of it. That was the thing I thought about the most. We’re all in a funk, so I thought maybe I can make people smile a little bit with this music.

You did a livestream event to mark “Here and Now’s” release. Does that kind of thing feel natural to you?

No. I’ve just spent so many years connecting in a certain way that it feels disingenuous to me. Not saying it’s disingenuous for anyone else to do it, but for me and my audience, to do a whole show like that — it just seems less-than.

Had you gotten this year’s production on its legs when everything shut down?

We were building the beast when all this went down — literally in the middle of designing the light show and getting all the video content together. Me and the band were rehearsing all the time. Then all of a sudden it just stopped.

Did the reality of the situation hit you immediately?

We just saw it sliding south. As we got into March and festivals started canceling — I saw the Stones move their stadium dates — I got really nervous, as anybody would be that employs as many people as I do.

How many folks are we talking in your band and crew?

I have 120 employees. Thank God I don’t have to let anybody go this year. Now, if we don’t play the next two or three years, it’s really gonna change the dynamic of my life. And I’m not gonna lie — it’s expensive.

What’s it cost to keep everyone employed?

I don’t want to get into numbers. But it’s a lot of money. A lot of money. The initial shock of it, I looked at the numbers and went, Oh my God, this is overwhelming. And, look, it’s affecting my life — I’m not gonna say it’s not. But I had to make a decision if I was gonna keep my lifestyle the way it was or if I’m gonna take care of my people.

So no new fancy sneakers for now.

I’m such a creature of habit, I’ve worn the same clothes since college. But, you know, I’m not the only one with a crew and band that’s feeling this emotion. What it’s done to the whole touring landscape is just unprecedented.

It’s hard to know when 80,000 people will be eager to jam into a football stadium.

And there’s nobody to look to for the answer. There’s no wise old man in this.

Would you consider playing smaller venues if that got you back on the road faster?

Well, yeah, if I’m forced. I’m gonna play where I can play. I’ve thought about doing theaters with me and a couple of players.

Do you remember your last stadium show in Baton Rouge? You didn’t know at the time that it might be years before you were back in that kind of space.

I don’t, really. We were having a great time, but we were tired. I knew I was gonna get on my boat, get off my diet for a little bit, come out to California and get away from it all. But in my brain I was also making this record that just came out. And I knew I’d be ramping back up [to play shows in 2020]. I wasn’t thinking about not playing.

You must be craving the affirmation you’re used to getting onstage.

That’s the struggle — it truly is. To feel that every night, to get that serotonin release, it’s not normal. I’m not depressed. But I feel the sense of loss this year.

Anything you can turn to, to replace that feeling?

Nothing healthy.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.