The Strokes’ Julian Casablancas on staying home (not too bad), the state of our democracy (really bad)

- Share via

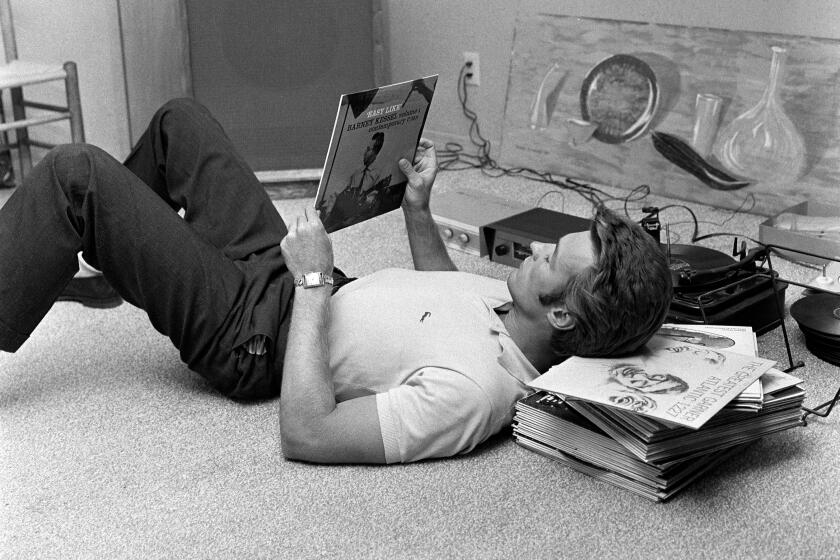

Julian Casablancas of the Strokes didn’t sound especially bummed to be stuck at home the other night when he picked up the phone at his place near Venice Beach.

“I mean, I generally don’t love going out Friday night anyway,” he said with a sigh. “So for me personally this whole thing” — sheltering in place amid the coronavirus pandemic, he meant — “has been kind of fine. Gotten to some of the things I’d been putting off. Been cooking a lot, which is good.”

The quiet-nights routine would’ve been hard to imagine when the Strokes emerged two decades ago as the foremost exponents of New York’s stylishly profligate garage-rock revival. But much has changed since the early 2000s, when Casablancas — the son of a Danish model and the founder of Elite Model Management — was writing nervy, hopped-up tunes about his after-dark adventures on the Lower East Side.

The latest updates from our reporters in California and around the world

Now 41 with two young children, the singer cuts a more introspective figure on the Strokes’ latest album, “The New Abnormal,” which came out Friday bearing a title eerily suited to these strange times. The band’s sixth full-length — and first since the coolly received “Comedown Machine” in 2013 — it’s slower and moodier than the band’s early stuff, with lots of dark ’80s-pop synth textures and some luscious falsetto by Casablancas.

“All my friends left / And they don’t miss me,” he moans in “Why Are Sundays So Depressing,” while the tender “At the Door” has the frontman “lying on the cold floor … waiting for the tide to rise” — one of several lyrics on the album that seem to refer to his divorce last year from Juliet Joslin, to whom he was married for 14 years.

Produced by Rick Rubin at his Shangri-La studio in Malibu, the very pretty yet vaguely sinister “New Abnormal” is as close to an L.A. album as the Strokes have made; two other members, guitarists Nick Valensi and Albert Hammond Jr., live here these days as well. (Bassist Nikolai Fraiture and drummer Fabrizio Moretti remain in New York.)

It also feels shadowed by the political awakening Casablancas explored on the two records he made with his electro-punk side project, the Voidz. In February, the Strokes played a campaign rally for then Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders where they blasted through the sneering “New York City Cops” — famously pulled from the band’s 2001 debut after 9/11 — as uniformed police officers attempted to clear the stage.

Beyond raising money for Sanders, whom Casablancas described as the first political candidate he’d ever publicly supported, that gig was meant to preview a world tour the Strokes had planned behind “The New Abnormal.” Now, of course, the tour is on hold thanks to the coronavirus.

Nobody would choose this moment to put out a record if they’d known in advance what was coming. Did you consider pushing back “The New Abnormal”?

The idea came up, I suppose because we can’t really promote it. But it didn’t seem worth postponing.

You don’t strike me as somebody dying to do tons of promo anyway.

Oh God, no. People are like, “Oh man, you’re not able to tour!” I’m like, “That’s a bad thing?”

The five of you are doing a series of hilariously awkward video chats.

We were gonna do radio shows, and since we can’t be together, five-way audio seemed too confusing. So it turned into this. Obviously we’re not TV personalities.

The stilted conversation has fed the narrative that grew up around the last couple of Strokes albums. People say the music makes it obvious you all hate one another.

I wonder which chords are making people think that.

It’s that the songs seem to be pulling in different directions — that they don’t cohere like on the first album.

Man, I might be just too much in the bubble to comment. The way I see it is so different. Cohesion? Because we played the first album live, maybe, is what people are talking about.

How do you think of this record in relation to the Strokes’ others?

I don’t.

I’m not asking you to rank the Strokes albums.

No, I will. It’s my fourth favorite record I’ve ever been a part of.

Behind which three?

Now you’re getting greedy.

Indulge me.

First two Strokes records and then maybe … you’re gonna get me in trouble. Let’s leave it a mystery.

How to keep Coronavirus stress at bay: Listen, really listen, to your favorite albums, front to back, without distraction.

Does something like the coronavirus crisis set your artistic mind in motion? Or do you shut down creatively?

I don’t think it has an immediate effect. I don’t believe so much in inspiration. I feel like I’m always kind of working and thinking about stuff; I don’t sit around and wait for inspiration. But long-term, who knows? It might just be sinking in now and come out in a year or five years from now.

Right — I’m eager to hear what comes from having processed this.

I think that’s why the name of our album feels fitting. “The new abnormal” was something [Gov. Jerry Brown] said during the Malibu fires [in 2018], and there’s a parallel between global warming and the coronavirus. A similar kind of threat to your reality.

What do you make of the government’s handling of the pandemic so far?

Not ideal. The South Korean testing seems like it would’ve been the smartest thing to have invested in. But then again, who knows? I know it’s instinct to want to blame someone, and maybe it could’ve been reduced — or can be reduced — by more action. But America is a large country, so I don’t know if it was possible to even stop it.

Is there something about the American mindset that makes it tough to sell a stay-at-home order?

It’s just hard to understand the statistics of it. Unless you know someone who got it, it almost doesn’t feel real to people.

Do you understand the statistics of it?

I have kids, so that made it easier to be serious about it. I think if I didn’t have kids or I was a teenager or something, I could imagine not really caring. It highlights, unfortunately, that people are selfish. It’s similar to global warming. People can understand theoretically that they’re destroying the environment, but it doesn’t compute because it’s a nice day outside.

How do you talk to your kids about the virus?

You try to put them at ease. You tell them it’s something that disproportionately affects the elderly or people that have health issues already. You try to be honest but give the lighter facts. Kids can sense something’s going on.

Does that nurturing role come naturally to you?

I don’t think I had that so much before kids. Probably the opposite. But it’s a balance: You want to protect them from intense darkness that can damage them, but you want them to get their lumps and feel enough reality and emotional truth to be tough and ready for the real world.

Former Times staffer Robert Hilburn opines that from his debut album in 1971, John Prine, who recently died, was one of the greatest songwriters America has ever produced.

Do you believe that President Trump will use this pandemic as a power grab to subvert our democracy?

I don’t think he needed this as an excuse. Also, I don’t know if you could really argue that technically — depending on how you define democracy — that we even really have that in the first place.

What’s your vibe on November’s election?

The only way I see [Joe] Biden winning is if he chooses Bernie as his running mate. And I don’t think he’ll do that.

Will you vote for Biden?

I mean, I think you have to. I hope he wins. But I understand why he wouldn’t.

How did you take the news that Sanders was dropping out?

I have a lot of respect for Bernie, and I want to be delicate here. I feel like when he lost the first time around, in 2016, it was definitely the DNC [Democratic National Committee]. It was pretty obvious that they angled him to lose. And to be honest, the same thing was going on here. The exit polls always came out much stronger for Bernie than the final result. Seems like voting is not kosher. But this time I felt like he really had a chance to circumvent that. I don’t exactly know the back-room games the DNC played, but I wish he could’ve gotten the endorsements of the other candidates. I mean, [Elizabeth] Warren didn’t endorse him. [Rallying support] is a skill the president needs.

When everyone endorsed Biden, I really felt like it was over. I was talking on the phone to some of the Bernie people — like, “What can we do? Can I go serenade Pete Buttigieg? Can Bernie promise him the vice presidency?” I don’t know how Bernie feels about it, but some of the people in his camp were like, “We don’t really want his support.” That’s when I was kind of hurt and sad. I’m glad that Bernie is so pure and noble. But there is an element of strategy that people like MLK [Martin Luther King] were always aware of. And I don’t know if Bernie was operating in a place that was too pure.

Buttigieg is probably a Strokes fan. Your serenade might’ve gone somewhere.

I like Buttigieg. Honestly, the whole Democratic panel, it seems like if they ran the government as a council, it probably would be overall headed in the right direction. We’ll see what happens. There’s a part of me — a grim part of me — that wonders if someone like Trump wins again, it might just reignite the awakening even deeper than it has. I got into politics the second time Bush won — that’s when I was like, “What the hell?” And I feel like that might happen again.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.