How director Dawn Porter was able to tell John Lewis’ story in ‘Good Trouble’

- Share via

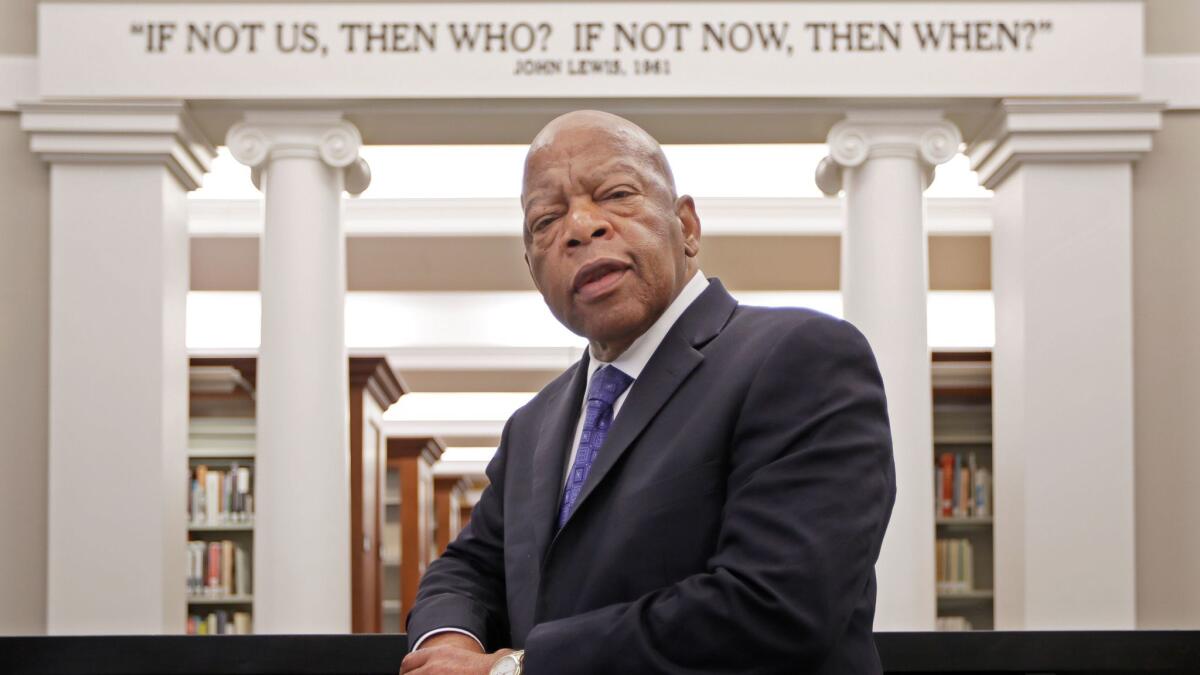

John Lewis has led a life arguably too large for a movie. Yet the new documentary “John Lewis: Good Trouble,” which is available now via video-on-demand, tries to capture not only the scope but also the spirit of this longtime activist and legislator. The film travels from the fateful day when a young Lewis was beaten by police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., to his becoming an elected congressman from Atlanta to the present. Lewis, now 80 years old, announced he was being treated for cancer late last year.

Director Dawn Porter is a widely acclaimed documentary filmmaker. Her “Gideon’s Army” detailed the work of public defenders in the American South, while “Trapped” looked at the laws governing abortion clinics. “Spies of Mississippi” was about a campaign to bring down the civil rights movement of the 1960s, while “Bobby Kennedy for President” was a four-part docuseries. She is currently at work on a film about Pete Souza, the White House photographer for President Obama.

“Good Trouble” features interviews and testimonials from established figures including Hillary Clinton, Bill Clinton, Jimmy Carter, Nancy Pelosi and Elijah Cummings (who died in October 2019 and to whom the film is dedicated), but also younger political activists such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Stacey Abrams, Ilhan Omar, Cory Booker, Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib.

Porter recently got on the phone from her home in Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., to talk about creating a portrait of John Lewis and capturing his formidable legacy.

As a filmmaker, you’ve made a number of films set in the American South. What keeps drawing you back there?

Dawn Porter: I think I don’t mean to keep going back there. The topics that I’ve been interested in have drawn me there. So for “Gideon’s Army,” that’s where all the public defenders were working. And then I made a film called “Spies of Mississippi,” for PBS and that film was set in Mississippi. And while I was there, I read about the abortion clinics closing [and then made “Trapped”].

I tried to get out of the South in making “Bobby Kennedy for President,” which was firmly New England. But John Lewis — in a lot of ways working on the Bobby Kennedy series, I was kind of in that head space of being in the 1960s and thinking about civil rights and thinking about, “How did leaders make their way? What did they actually do?” I think a lot of us right now are thinking, “What would we do?”

People want to believe there’s some magic to people who step up and do things. And I don’t think that there is any magic. [With John Lewis] what you see is what you get. He couldn’t stand segregation and he decided to do what he could to stop it. He’s just a determined, straightforward person.

Maybe it says something that that’s so rare, that people believe there must be something else. And I’m like, “That’s it, he hated segregation.” That’s what it was. That’s what motivated him. And I think he found that he was good at it. He was good at organizing and it made him feel good, it made him feel productive when he otherwise felt powerless. He saw what his choices were: “I can be powerless or I can try and do something, but the life I have, the life that has been selected for me, is not the life I want. So I have to figure it out myself.”

When you come onto a project like this, knowing how big John Lewis’ life is, where do you start?

It’s not easy, to tell you the truth. When you’ve lived for 60 years as a public servant and you’ve written several books. So I’ve watched as many things as I could find about him or places where he was included. I read a number of articles, I read history. And then I tried to look and see, “What else, what do I have to add?” But I don’t want to make a film that’s a book report. I don’t want to make a film that is only overstating what we already know.

And there’s this question of what happens to old civil rights leaders. There’s so many of them who we have to resuscitate their names, and that wasn’t what happened with him. He shifted in a way that allowed him to continue his work. But I think he changed, along with the work. When you are the activist, you’re kind of pushing, pushing, pushing, but when you’re the legislator, you have to have a different approach to making change.

The movie includes scenes of Lewis sitting in a chair and watching old footage of himself — there’s something very simple about it but also very striking, especially to see John Lewis as he is now with an image of his younger self. Where did that idea come from?

We were filming with him in Alabama. And as part of that trip, we all, as a large group, went to Bryan Stevenson‘s civil rights museum. I was watching the congressman and he was watching an exhibit about himself. There was all this great archive footage and he was shaking his head. And he said, “Sometimes I can’t believe that’s me,” and he turned to his left. And there was a teenager. I mean, can you imagine being on a high school trip and the guy in the exhibit is next to you? He starts telling this kid a story I hadn’t heard him tell before.

It gave me the idea: “Oh, if I show him some things, I could bring him a little bit back in time.” Particularly with people who have a very public life, and so they’ve spoken a lot about their experiences, I knew that I needed a way to get some additional information from him, to get him to tell new stories. So we created these small mini-films of just archive and then we constructed three huge screens and put him in the middle and turned the lights down. Then I just asked him to tell me the story of those times, which he did.

And so in the middle of that, he says, “I’m seeing things I’ve never seen before.” As much as any one moment, I think it was also the totality of it, because it was just all of these huge moments that he was part of. Like I didn’t remember that he spoke at the March on Washington. I know he remembers it. And to see sit-ins and training and marching and getting arrested, and then after he’d already been beaten so badly on that bridge to then start the freedom rides and walk again into the fire. I mean, most of us spend our lives trying to avoid pain. John Lewis continuously walks into it.

There’s a line I love from Bernard Lafayette, when he’s talking about the sit-ins, the kids and how they kept going every day, they kept going back, even though they were treated so terribly. And he says, “We kept giving them the opportunity to change.” And I just love that phraseology. It’s the most positive way you could think about it. Instead of being angry — he and people who are religious — he said they had the opportunity to change. “We’ll give them another chance tomorrow.” And you know what, eventually that change did happen.

Do you feel like the movie will play differently now, being released amidst the Black Lives Matter protests, than when you were making it? What does it mean to you to have that be the environment the movie is actually being released into?

There’s no doubt that ... it’s a much more sober time and a reflective time. I think before the murder of George Floyd, before the pandemic, before we all felt this vulnerability to things out of our control, I think it might have been harder to get people’s attention and to realize how important all the things that John Lewis has worked for in his life really are. And by that I mean equal access to voting, speaking up when you see brutality and police violence, having good government, having a functioning democracy. I think in a lot of ways people tend to take those things for granted. And the movie doesn’t have to do that work anymore.

It doesn’t have to do the work of saying, “This is why you should care.” Unfortunately, we can’t chase the news in a documentary. Once you finish it, you finish it. We finished this in December. So it would have been great to have him reflect on what is happening, but we don’t have that. But I am 100% sure, I’m positive, from speaking with him, from speaking with his chief of staff, how important this moment is for him. Particularly because he’s been ill, he’s not been able to keep up the same schedule that he had before. So when he goes down and poses in front of that Black Lives Matter art installation in front of the White House, I think he’s telling everybody what he wants them to know, which is this is what gives him hope.

This is what keeps him optimistic — we did not have protests against police violence in all 50 states when John Lewis was beaten. And today we do have that. So for people who say nothing has changed, that’s just not true. I think that helps him not be as depressed about current events as other people, because he never thought that he was finished.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.