These Sherlock Holmes films have gone missing. UCLA and Robert Downey Jr. are on the case

- Share via

More than a century after Arthur Conan Doyle published his first Sherlock Holmes mystery, a new investigation is afoot. But this story features more local detectives.

The UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Baker Street Irregulars, America’s foremost Sherlockian society, are on the case with “Searching for Sherlock: The Game’s Afoot,” a mission to recover and restore missing Holmes films from the silent era and beyond. The project, honorarily chaired by “Sherlock Holmes” franchise star Robert Downey Jr., reflects a continuing ongoing global fascination with Conan Doyle’s amateur detective that has spurred countless onscreen adaptations, lost and found.

“Sherlock Holmes is really an international phenomenon,” said Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. “We decided that it would really be worthwhile to, first of all, do a research project and find out how many of these Sherlock Holmes films survived and in what condition, and what we at UCLA Film & TV archive could then do to preserve some of them.”

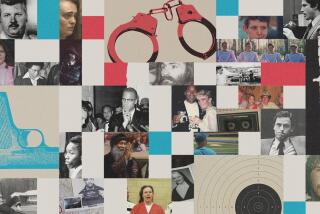

Sherlockians and film historians weigh in on their favorite Sherlock Holmes adaptations, from 1916’s “Sherlock Holmes” to 2012’s “Elementary.”

Horak estimates that more than 80% of American films from the silent era alone have been lost because of eroded prints, mislabeling, fires and other causes. Because the circumstances of their disappearances are so varied and unpredictable, it’s hard to say exactly how many Holmes adaptations wait to be discovered. But they are aware of some that may still be out there based on evidence of prints of long-lost films.

“It’s not like there’s a list anywhere,” Horak said. “I’m assuming that the great majority of the films from the silent era, when the most were actually made, are actually completely lost. But there are films that survived — that we know have survived.”

Finding the bygone works will, appropriately, require a bit of sleuthing, starting with contacting the Library of Congress and New York’s Museum of Modern Art, as well as historians, collectors and national film archives in Britain, Germany, France and other countries. Such efforts have seen previous success, particularly in the case of the missing 1916 Holmes production starring American actor William Gillette, which later turned up in 2014, mislabeled in Paris.

Like the best Holmes stories, the odds are daunting — but not impossible.

“Many of those hundreds [of films] are lost in the sense that there are no known copies,” said Baker Street Irregular and Malibu resident Leslie Klinger. “We know about the film, but nobody’s seen it for a generation or more. And we’re hoping that copies exist out there.”

While the hunt for Holmes officially kicked off last month, obsession with Conan Doyle’s neurotic private eye is hardly novel. Conan Doyle’s page-turners were wildly popular when they debuted in late-1800s literary magazines. They’ve since inspired hundreds of books, TV series, movies, plays and even college curricula — as well as around 300 Holmes societies worldwide, from Canada to Japan.

“There aren’t many works of fiction — in English, at any rate — that are still read after over 100 years because people want to read them, not because they’re told to,” said Roger Johnson, a member of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London. “When I was at school — even when I was taking my degree in English — the idea of studying Sherlock Holmes would have been considered almost unthinkable. But people do now. ... It’s an extraordinary phenomenon, and it’s gotten bigger with the increase in Holmes onscreen.”

Klinger, known as “the world’s first consulting Sherlockian” for his advisory work on projects including the Downey Jr. movies, has some hunches as to why the Victorian-era detective continues to capture the imaginations of readers, viewers and artists to this day.

“I like to call him an attainable superhero,” Klinger said. “We don’t have to find a radioactive spider to bite us or be born on another planet. We just have to work really hard and study so that we can be like Sherlock Holmes.”

But like all heroes, even the great Holmes has his kryptonite, whether it comes in the form of substance abuse (cocaine was his drug of choice), red herrings or sharp-witted femme fatales such as Irene Adler.

“He’s not perfect,” Johnson said. “Even as a detective, he’s a great detective but he’s not perfect. He gets things wrong — occasionally — but it makes him more human, and that’s something we can relate to.”

In addition to Holmes’ appeal as an accessible yet fallible beacon of justice, some Sherlockians speculate that nostalgia also plays a role in luring audiences back to Baker Street. If anyone can deduce why Conan Doyle’s creations continue to inspire, it’s Nicholas Meyer, who authored and adapted the screenplay for “The Seven-Per-Cent Solution” — Oscar-nominated Holmes fan fiction — and is currently working on another Sherlockian caper titled “The Adventure of the Peculiar Protocols.”

“Holmes exists — or at least initially existed when Doyle created him — in a world that was long enough ago to seem like a kind of fairy tale place or a fairy tale time,” Meyer said. “Perhaps, a time we like to tell ourselves was a saner time.”

That logic only stretches so far, however, when it comes to more recent small-screen adaptations such as “Sherlock,” the Emmy-winning BBC series starring Benedict Cumberbatch, or “Elementary,” a CBS hit featuring Jonny Lee Miller as Holmes and — notably — Lucy Liu as a rare female version of Dr. Watson. Both shows update the timeline of their source material to modern day, trading hansom cabs for subways and limousines.

“It turns out that you can put these two people into almost any landscape,” Meyer said. “You can make Watson a woman; you can call them Batman and Robin — it doesn’t make any difference. It’s the same idea of heroes who are fighting against anarchy and trying to be right.”

Liu isn’t the only woman to portray Watson. “Miss Sherlock,” a Johnson-approved Japanese series, flips the genders of both the titular detective and his loyal companion. In fact, according to Johnson, discussions have even swirled among Sherlockian societies as to whether Conan Doyle intended Watson to be female all along.

“There is no real reason why Watson shouldn’t be a woman,” Johnson said. “You have to ignore things like his mustache ... but when you translate the character into a woman for dramatic presentation, it works.”

With all the changes and updates the Holmes stories have successfully adopted over time, it’s not easy to pinpoint the fundamental elements of a good Sherlock Holmes adaptation — even for film and Holmes scholars.

“I can think of a time when I would have said fidelity to the original story,” Johnson said. “It’s fidelity to the spirit of the originals. I think that’s what it is.”

With “Searching for Sherlock,” Horak hopes that the archive can screen and upload some newly restored Holmes material to its website within the next few years. Despite all the witty modernizations and computer-generated bells and whistles that have since embellished the Holmes canon, Sherlockians and film historians agree that the earliest Holmes films — should they be recovered — still have great potential to teach and dazzle 21st century audiences.

“It doesn’t really matter whether it’s silent or talkie; it doesn’t really matter whether there were fancy special effects or not,” Klinger said. “We’re going to be gripped by the personalities and intrigued by the mysteries and also be satisfied that reason has prevailed. Evil has been conquered.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.