Every Hollywood studio passed on ‘Bull Durham’ twice. How it got made anyway

- Share via

There’s a temptation when speaking to directors of classic films to ask whether their career-defining movie could get a studio’s green light today. The glossed-over reality, often, is that those pictures barely got made, even at the time.

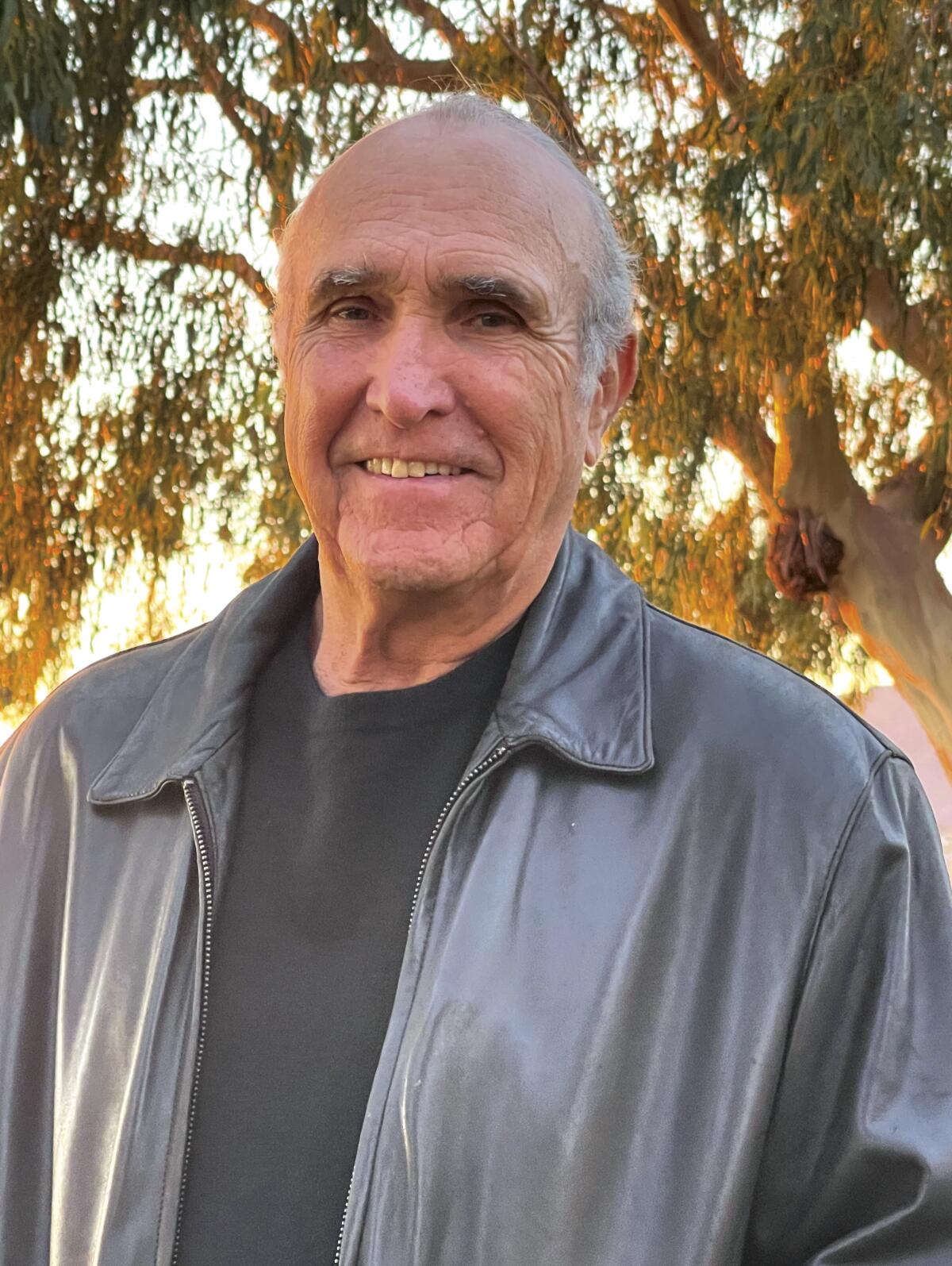

The script for 1988’s “Bull Durham,” an unconventional comedy set in the world of minor league baseball, was passed on by every studio in Hollywood. Twice. The second time screenwriter Ron Shelton made the rounds, he was joined by Kevin Costner, who would play the aging catcher Crash Davis. Still nothing.

The two had a 30-day window, imposed by Costner’s agents, to convince a studio to finance the movie, or Shelton would lose his star to a Warner Bros. project. At 3 p.m. on the day of the deadline, Shelton got a call. Orion Pictures was on board. What Shelton didn’t know at the time was that Orion had just received a confidence boost about Costner. The Costner-starring political thriller “No Way Out” had opened that morning to a rave review from Vincent Canby in the New York Times.

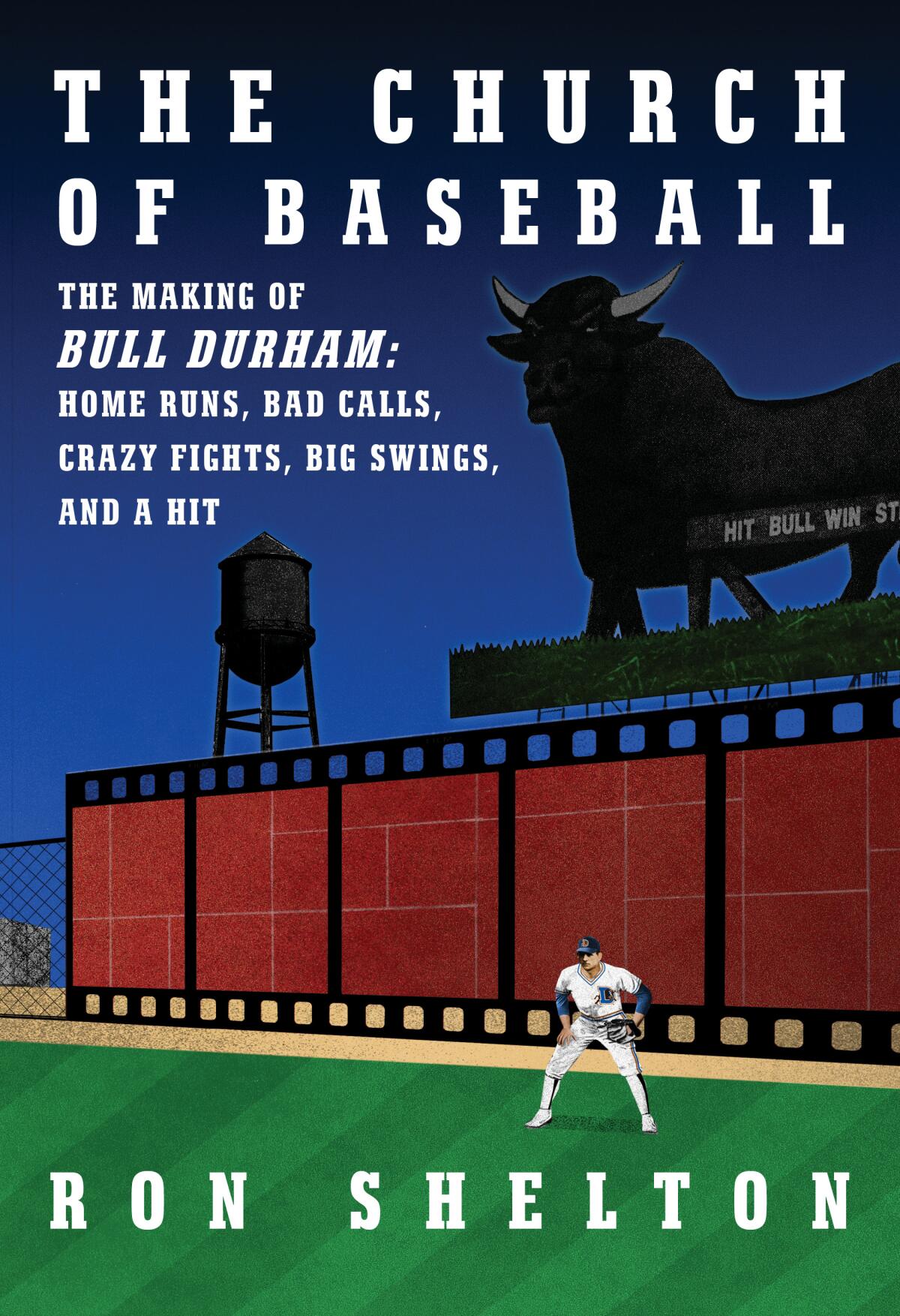

“Any other kind of review and ‘Bull Durham’ might never have been made,” Shelton writes in “The Church of Baseball: The Making of ‘Bull Durham,’” which came out this month from publishing imprint Knopf.

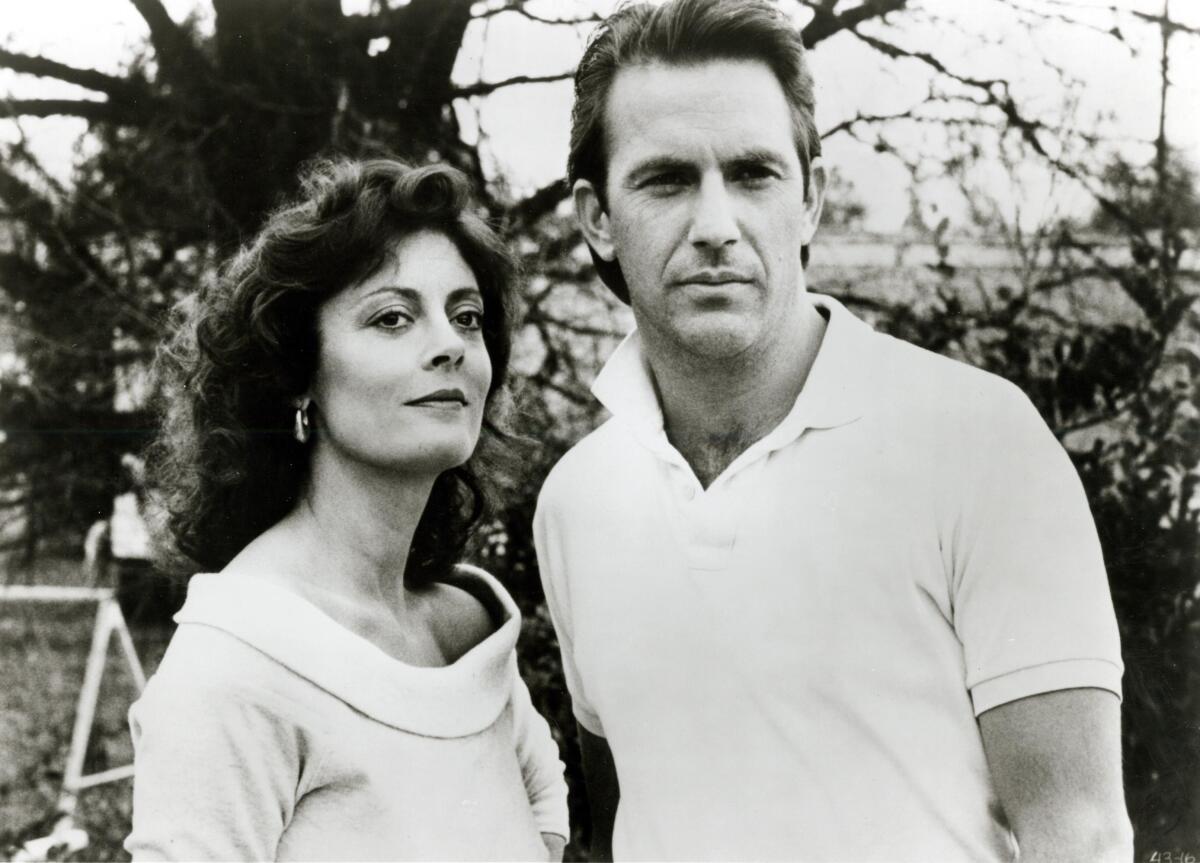

The close call is one of the many illuminating anecdotes in Shelton’s book, which is at turns a making-of memoir and a guide to Shelton’s creative process, going into the details of how he absorbed his own minor league baseball experiences into the script and tussled with studio executives throughout the production. The studio didn’t like Tim Robbins’ performance as the young, wild-armed pitcher pining for the big leagues. They didn’t think Susan Sarandon looked good as Annie Savoy.

But the film was a hit, grossing about $50 million, which would equal well more than $120 million in today’s dollars. Shelton received an Oscar nomination for the screenplay and went on to write and direct “White Men Can’t Jump” and “Tin Cup” (the latter also starred Costner). Today, “Bull Durham” probably would be made for Netflix or Amazon’s Prime Video, perhaps as a limited series. Orion Pictures, once independent, is now a label within MGM, itself a subsidiary of Amazon.

The Times spoke with Shelton about the current state of sports movies, the agonies of studio notes and why third acts are overrated. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s talk about the state of sports movies now. There was “The Way Back” with Ben Affleck, “King Richard” with Will Smith and then “Hustle” with Adam Sandler. But there used to be at least a couple of them every year, it seemed.

I think we’re being strangled by algorithms. I think the sports movie goes into the computer and the computer doesn’t know what to do. The algorithm says, “This doesn’t sell in Bulgarian television,” or something. Sports movies tend to be domestic-driven, because we don’t make movies about sports other than the ones we play in North America. And I don’t think the studios or the networks are run by riverboat gamblers anymore. They’re run by committee. These kinds of movies are gut-instinct movies. They go against the grain because they don’t check all the boxes for an international audience. It’s why nobody wanted to make “Bull Durham.” They said there was no foreign business. Well, I’m still getting residual checks for North American rights.

“The Queen’s Gambit” is about chess but follows the format of sports movie. I’ve seen the argument that “Top Gun: Maverick” is basically a sports movie with F-18s. Has the genre just been hoovered up and incorporated into other types of film?

Yes, it has. I don’t think of “Top Gun” as a sports movie, but I understand the underlying paradigm. Stories that are interesting are not the stories about the winner of the Super Bowl or the heavyweight championship. It’s about everybody else trying to win the Super Bowl. If Rocky wins, nobody remembers the movie. Rocky goes the distance and loses, and a franchise was born. And that’s the right ending. If Woody Harrelson ends up with Rosie Perez in “White Men Can’t Jump,” I’ve disrespected the Rosie Perez character and the whole idea of what the movie’s about. And if Crash Davis gets to the big leagues, that’s a false ending.

Part of what’s interesting about “Bull Durham” is that it doesn’t have a third act. There’s no big game. There’s really not that much sports in it at all. But that’s how the movie is able to end so naturally. There’s this feeling of inevitability, that it can’t end any other way.

Yes, exactly. When Tim Robbins’ character, Nuke, is removed from the movie because he’s going to the big leagues, that removes the barrier to Crash and Annie getting together. But that’s not a good act break, because it’s something that just happens. It’s not something that a protagonist makes happen. So it’s really an obstacle removed; it’s not an act break. So guess what? I’ve got two acts. Who cares?

You write that every studio passed on “Bull Durham.” What was it that got this film over the edge for Orion Pictures?

Sheer luck. On the morning of the last day that I could hold onto Kevin Costner, his movie “No Way Out” opened in New York to a rave review from the New York Times, which declared that Kevin Costner was going to be a huge movie star. “No Way Out” was released by Orion Pictures, who we’d given the script to the night before for the third time. They woke up to this review and they have Kevin Costner’s next movie if they want it. Had “No Way Out” not opened to a rave review that morning, this movie would never have been made. The irony is, the only reason “No Way Out” opened in August was because Orion didn’t know what to do with it. That’s where you used to send movies to die. But it was a hit, and it allowed a bigger hit, “Bull Durham,” to be made.

There are many funny stories about casting the movie. Anthony Michael Hall showing up for the role of Nuke and admitting to never actually having read the script. Susan Sarandon wasn’t even on the studio casting list. How did she get cast?

She was living in Italy. She flew on her own dime from Italy to L.A. with her 2-year-old daughter and a nanny and basically insisted on an audition. And she got the part. But I’ll save the details for the book, because it’s a great story.

There’s a lot of stories in the book about disagreements with the studio suits. They thought Susan Sarandon didn’t look good as Annie. They didn’t like Tim Robbins.

They said it wasn’t funny and it wasn’t sexy.

These days, you hear about studios being stretched so thin that they don’t even bother to give notes. Is there a point where the quality-control pendulum swings too far in the other direction?

I would disagree with one thing. They shouldn’t give notes. Most of their notes don’t make sense. In defense of the executives, they haven’t been brought up in a system of apprenticeship. They come right out of USC film school or NYU and now they’re passing judgment on something that they have no idea what it’s about. Notes used to be minimal. “Tighten up the opening. The ending is unclear still.” That was a note. Now you get pages and pages of stuff that you can’t honestly figure out what they’re talking about. They may be spread thin. There may be too many movies and television shows being made. But they’re being made because a tremendous amount of money is being generated. So hire more of these guys, but give less notes.

In the book, you express little patience for companies making movies as loss leaders for theme parks. Now they’re making them as loss leaders to sell toilet paper and iPhones. Is this having a negative effect on the industry?

I’m not unhappy that a lot of movies get made that don’t interest me. When they sell tickets, it’s good for everybody making movies. I like everything to be a hit. It’s just that movies about human behavior are less and less on anybody’s schedule. But when they finally get through to the theater or on streaming, everybody loves them. I just think human behavior is the most interesting thing to make movies about. The audience is desperate for movies about human behavior. Funny, tragic, inspiring, whatever.

What do you hope people take away from this book about a movie that was made and released roughly 35 years ago?

First of all, I’m open with my criticism of the business. At the same time, I love and embrace the business. I’m part of this world. I think there’s things to learn about the creative process, about the willfulness and serendipity involved. That’s why I have a little tiny bit of memoir in the book, because everything that I share ends up in the screenplay and onscreen. It’s a connection between life and art. Maybe that’s what the point of the book is.

If someone came to me — like the LIV Golf league except not with Saudi money — and said, “We’re gonna give you $100 million to write movies, but they have to be about the Death Star or the Andromeda galaxy,” I would have to say, “I’m sorry, I can’t take your money.” I’m not good at certain kinds of storytelling, but I’m really good at other things. I just write what I know. That’s all I can do.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.