Why streaming’s ‘great re-bundling’ won’t save Hollywood as we know it

- Share via

Welcome to the Wide Shot, a newsletter about the business of entertainment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

A helpful and depressing way to understand why today’s television and streaming business is such a mess is to consider how good media companies had it not too long ago.

We’re talking about the heyday of what media executives call “linear” television.

You’d turn on a channel at a certain time, on a specified day to see a particular program. You’d pay a monthly bill for a big bundle made of an extraordinary number of channels, even if you’d only watch a handful of them while ignoring the rest.

You know it as the hated cable package. Or satellite, if that’s your deal. If you wanted to watch the NBA on TNT but didn’t care about “Property Brothers” on HGTV, too bad. You paid for the whole bushel, anyway.

This was a lucrative business for television distributors (Comcast, AT&T, Dish Network) who collect those bills, and also for the programmers (NBCUniversal, Warner Bros., Disney) that make the shows and earn fees from the service providers. Consumers in recent years watched fewer channels, according to Nielsen, even as the number of available networks broadly increased.

But the TV business was also bundled in ways that were less obvious to the major media conglomerates that decided to go direct-to-consumer. The various streaming options have revealed the degree to which the individual networks — such as AMC, CBS, HBO — are really, themselves, bundles of a variety of shows.

With streaming, those bundles untangled as easily as balls of yarn.

Doug Shapiro is a former Turner and Time Warner executive and corporate strategy expert who was previously a Wall Street analyst. Shapiro, who now writes a Medium blog about the media and entertainment business, succinctly describes the reasons for — and the economic consequences of — this mass disaggregation of the content industry.

Streaming subscriptions make it so easy to turn subscriptions on and off that customers can sign up for Paramount+, watch the latest “Star Trek” series and bail as soon as they’re done. So instead of paying $60 a month or more for a package of cable channels, they can sign up to watch whatever they want while spending very little.

“When the big media companies reluctantly launched their streaming services, I think that they believed that they were only unbundling a little,” Shapiro told me last week. “They didn’t realize that they were actually unbundling all the way down to the show level, because it’s so easy to churn.”

We can argue about how “reluctantly” legacy companies such as Walt Disney Co. jumped into the streaming business. To be sure, they were responding to pressure on a number of fronts: Netflix sucking up their power, plus Wall Street egging them on.

The results are plain enough, though. The business is worse than it was even a few years ago.

Shapiro laid out, in a recent blog post, how traditional video “over-monetizes” compared to streaming, in terms of how much money it generates per hour of content people watch.

An analysis from SVB MoffettNathanson estimated that traditional TV monetizes at 57 cents per hour viewed as of last year. By comparison, the established streamers generate revenue at a rate of 27 cents to 42 cents an hour, or half as much as linear TV at the low end.

Shapiro concludes that the revenues and eventual profits generated by streaming will not fill the hole left by the decline of traditional television, which shows no signs of stopping its cord-cutting spree.

More than 14 million U.S. homes are expected to quit pay-TV by 2027, according to PwC’s recent forecast, representing a decline of more than one-fifth from 2022’s 64-million subscriber base. The projected total penetration of 49.9 million homes for cable and satellite in 2027 would be about half the nearly 100 million in the U.S. who subscribed as recently as 2016.

Not great.

This helps explain why some companies have tried to re-create their own mini-bundles, which are meant to improve customer loyalty at a time when churn is one of the defining problems of the streaming business (and, not to mention, newspapers).

Disney, for example, offers Disney+ with Hulu as a “soft bundle,” meaning customers get two apps with one credit card payment. Chief Executive Bob Iger has indicated that Disney intends to offer a “one app experience,” also known as a “hard” bundle, in which Disney+ comes with Hulu content included.

Another approach is the one Paramount Global is using with the consolidation of Showtime. Paramount+ subscribers have had the option to pay for Showtime as an upgrade. Now the premium version of Paramount+ will simply come with Showtime content, with the price going up to $11.99 from $9.99. Warner Bros. Discovery is taking a different tack by merging Discovery content into Max (formerly HBO Max), while keeping the same price, for now.

But there are limits to how far they can go. Now that consumers have tasted freedom, it will be very difficult to force them to pay for stuff they don’t want without a massive backlash.

“There will be re-bundling in the sense that there will be ways of giving consumers the flexibility to bundle stuff and save money, but I think any effort of forced bundling is not going to work,” Shapiro said.

A tech giant like Apple or Amazon could, in theory, try to re-create the cable package for streaming. But so far, no one’s shown much of an appetite for that, and predictions of an actual “great re-bundling” have yet to come true.

Shapiro argues that some bundles are more effective than others.

The best bundles provide options, such as the ability to downgrade easily, and make it clear to the consumer how they’re saving money with each package while getting more of the content they want. Bad bundles, to Shapiro, are ones that force the viewer into paying for things they don’t desire for the sole purpose of squeezing more money from them.

Media companies need to be thoughtful in how they approach the new bundles, lest they lose what goodwill remains among their already fickle audiences. After all, we’re a long way from the days where cable companies monopolized access to video. Consumers have options.

For more analysis of the state of the entertainment business, check out the Los Angeles Times’ Ultimate Guide to Streaming, which tackles a number of these topics in depth.

Stuff we wrote

— What makes a streaming hit? Desperate fans ‘game the system’ to save favorite shows. How platforms like Netflix and Prime Video measure success can mean the difference between life and death for a show. But those metrics remain opaque.

— Why Hollywood’s streaming future probably won’t look like TikTok. Netflix tried to launch a TikTok-like feature. Quibi collapsed pursuing a similar dream. Will Hollywood ever bottle the magic of short-form video?

— Skeptical about VR goggles? How Apple and Disney could create the future of entertainment. At Apple’s last big developer conference, Bob Iger announced that Disney+ would be available on the tech company’s new virtual reality headset. It could be a fad — or the future of mass media.

— Disney CFO Christine McCarthy is leaving the company. McCarthy, a longtime executive at the Burbank company, will go on family medical leave before exiting. Veteran Disney executive Kevin Lansberry will take over on an interim basis.

— L.A. Live’s Microsoft Theater will now be called Peacock Theater. Yes, after that Peacock.

— Sundance Institute gets $4 million to support Indigenous filmmakers. The nonprofit Sundance Institute said it will use the gift — its largest endowment ever — to support programs that boost emerging and mid-career artists.

— Weapons expert in Alec Baldwin case was likely hungover on set, prosecutors say. The armorer had been drinking in the evenings during filming, prosecutors say. Actor Alec Baldwin’s prop gun had a live round that killed the film’s cinematographer.

— The brutal year for Los Angeles media continues. Southern California Public Radio, which operates LAist and the station on KPCC-FM (89.3), has laid off 21 employees.

Numbers of the week

After the poor showing of Pixar’s “Elemental” at the box office ($29.5 million from the U.S. and Canada as of Sunday), it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the Disney brand needs to get its creative mojo back.

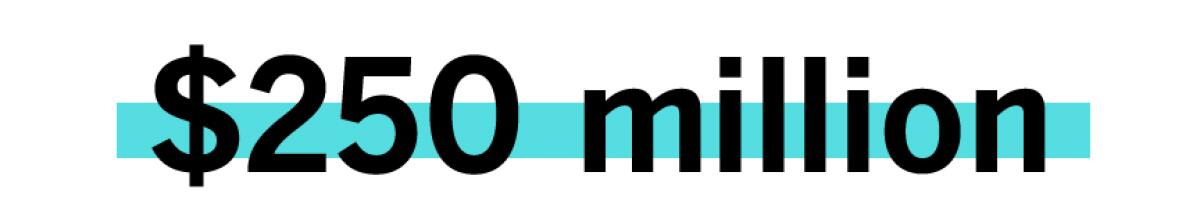

A group of 17 music publishers, including Universal Music Publishing Group, Warner Chappell Music and Sony Music Publishing, sued Twitter over “massive copyright infringement” involving their music catalogs. Publishers, who hold the rights to music from Drake, Taylor Swift and Adele, are seeking more than $250 million in damages. Elon Musk’s X Corp., which owns Twitter, is the sole defendant.

Best of the web

— Guillermo Del Toro gave some choice quotes about the state of the animation industry. (Hollywood Reporter)

— Danny McBride keeps it righteous. (New York Times)

— “You Knew It Was Something Really Nasty”: How the art department brings “I Think You Should Leave” to life. (Defector)

— What happened to Lara Logan? (The Atlantic)

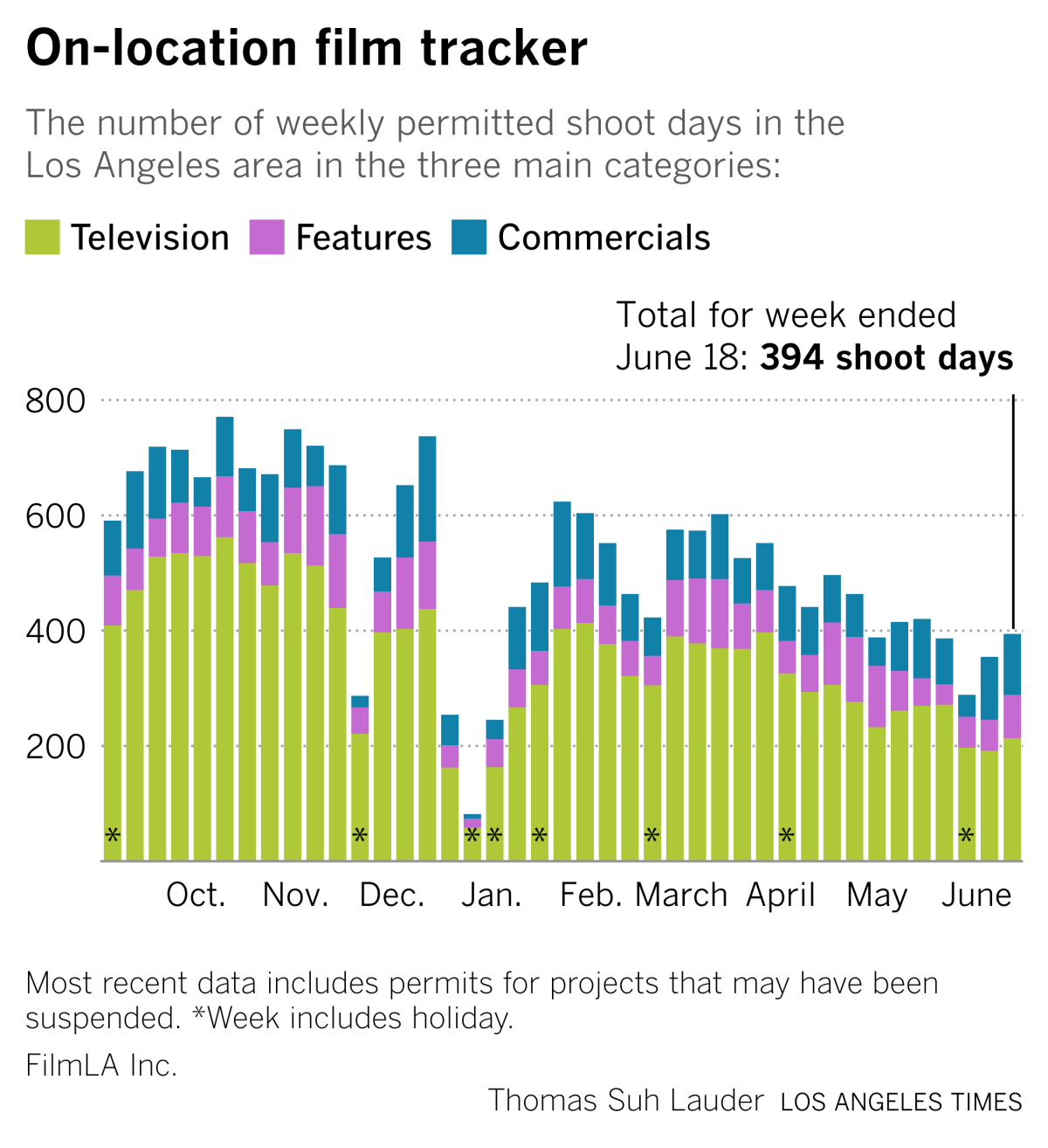

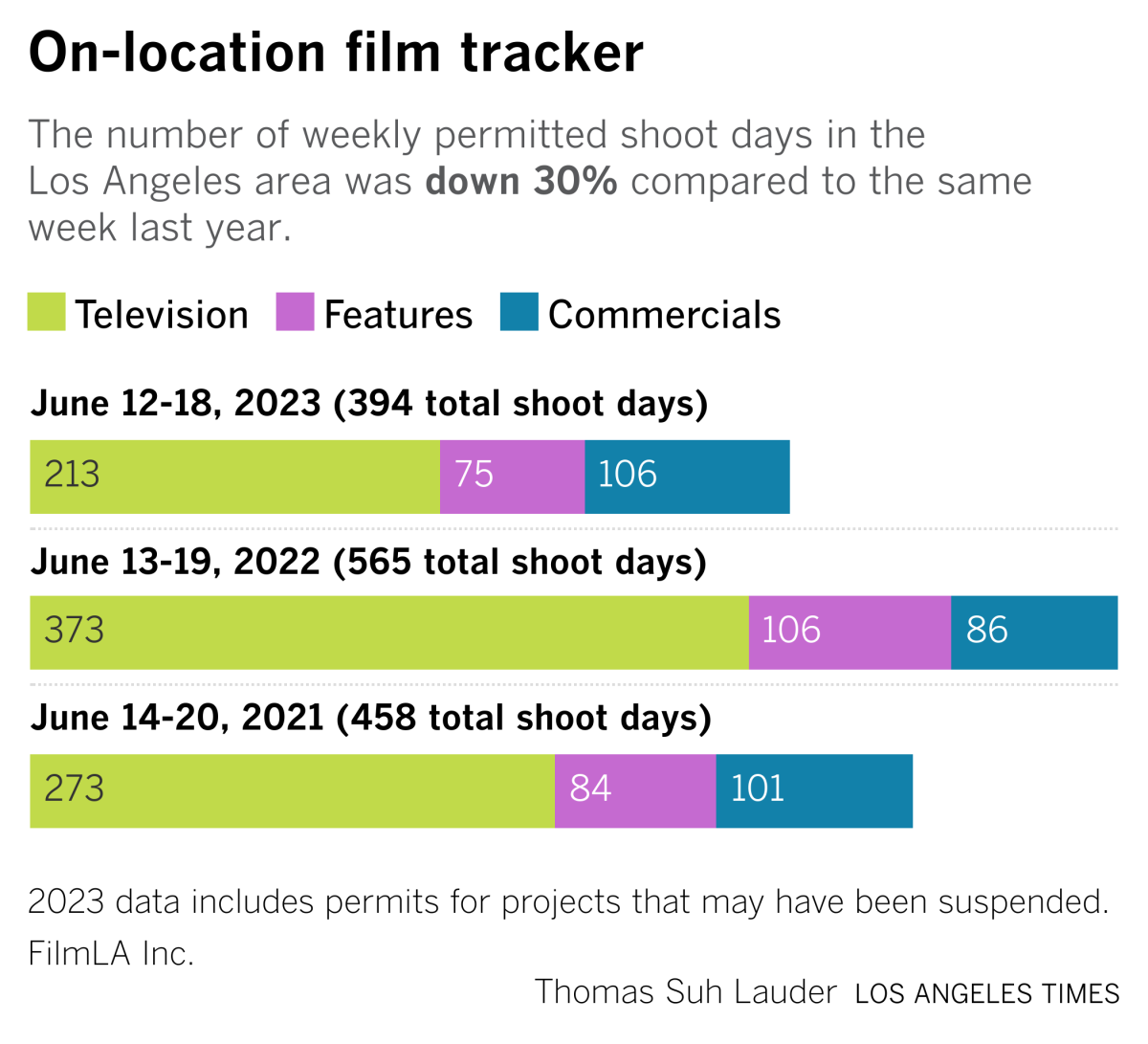

Films shoots

Latest on-location production data from FilmLA.

Finally ...

For Father’s Day weekend, I got to attend the first night of this year’s Hollywood Bowl Jazz Festival. Samara Joy, Kamasi Washington and Poncho Sanchez were fantastic, as expected. My big new discovery, though, was the eight-piece soul band St. Paul & the Broken Bones, of Birmingham, Ala. Catch them live, if you get the chance. (I’m late to this bandwagon.)

The Wide Shot is going to Sundance!

We’re sending daily dispatches from Park City throughout the festival’s first weekend. Sign up here for all things Sundance, plus a regular diet of news, analysis and insights on the business of Hollywood, from streaming wars to production.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.