Novelist Richard Ford’s Great American Gasbag takes a deflating road trip

- Share via

Review

'Be Mine: A Frank Bascombe Novel'

By Richard Ford

Ecco: 352 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Late in Richard Ford’s new Frank Bascombe novel, “Be Mine,” his hero is stopping in Rapid City, S.D., when he learns that all the area hotels are fully booked. A statewide high-school oratory contest is in town, and the kids are speechifying on “Why Do Americans Believe in Democracy?” “A good question I’d like to hear the answer to,” he muses.

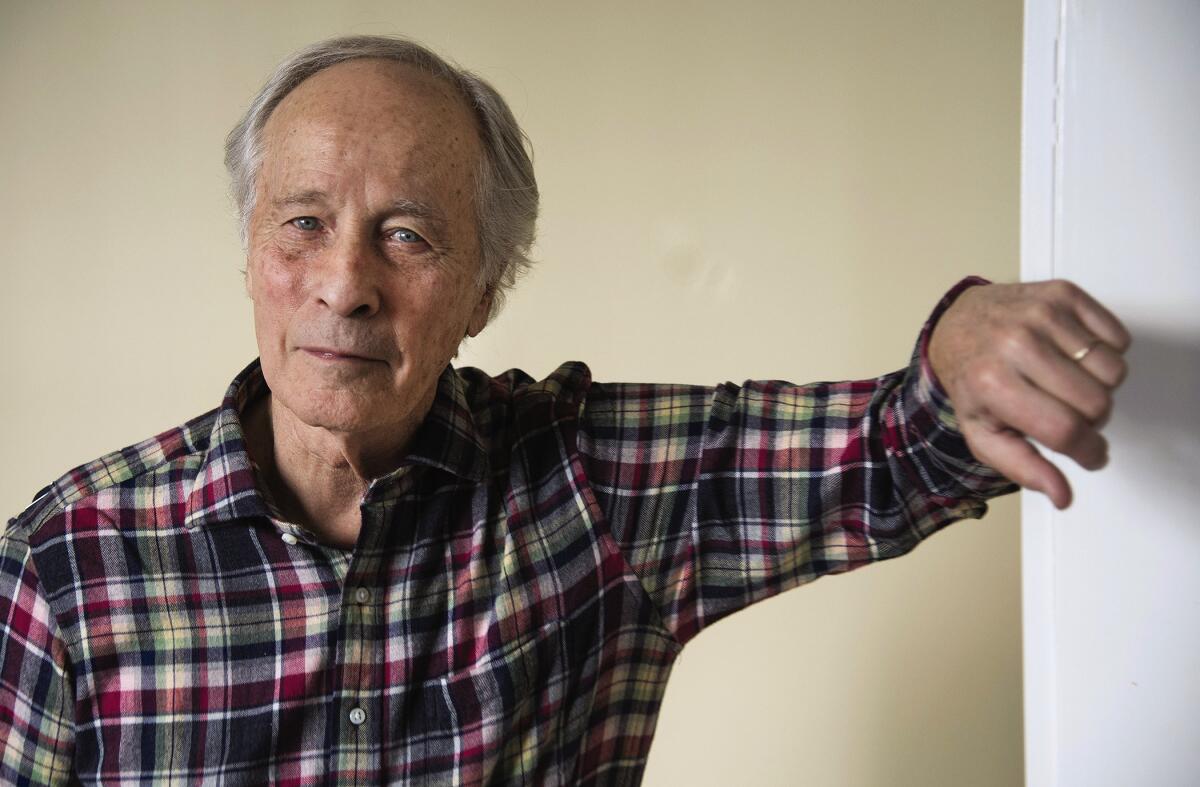

Well of course he would. Across five books, starting with 1986’s “The Sportswriter,” Bascombe has been Ford’s Great American Gasbag, a boomer riffing on money, marriage, parenthood, success, failure, democracy and the American way. Frank arrived at a time when literary fiction was studded with such men, from Walker Percy’s Binx Bolling to John Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom to Philip Roth‘s Nathan Zuckerman. Indeed, for a time, such figures were synonymous for many with American literary fiction — readers trusted middle-aged white guys and their fictional alter egos to synthesize the national experience.

In the decades since, enthusiasm for fiction that’s just middle-aged-plus white guys riffing on things has … diminished. Ford is aware: Frank, now 74 and reporting from the political wilds of 2020, is diminished too. Now that he is semiretired from the real estate business, his life has narrowed to caring for his long-troubled son, Paul, who is battling ALS. “When you’re in charge of a failing son little else goes on,” he says, with a hint of resentment from a man who wants to talk about everything going on.

The author’s new novel, ‘Canada,’ finds him acknowledging geography in a way he hadn’t before embraced

Like every Bascombe novel, this one is set in the days before a holiday, and this time Frank is shuttling Paul from Minnesota’s Mayo Clinic toward Mt. Rushmore, slated to arrive on Valentine’s Day. He’s alienated from Paul, a hard case thick with sarcasm and hobbies he can’t relate to. (Paul is a mediocre-at-best ventriloquist with an affection for British show tunes singer Anthony Newley.) The Hallmark holiday is a grim reminder that romantic relationships are absent for Paul and in the rearview mirror for Frank, who’s reduced to a kinda-sorta relationship with a masseuse. He writes her a Valentine’s Day card — with $200 tucked in, her usual fee.

Ford has always designed Frank to be a little pathetic: The tension in “The Sportswriter” and its two follow-ups, 1995’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Independence Day” and 2006’s “The Lay of the Land,” was always between Frank’s proclaimed virtues, success and wisdom and his shortcomings as a father or spouse. The thrill of those books was in witnessing how he tried to talk through the struggle, sometimes self-aware and sometimes not. He could be brought to heel — shot by an AR-15, breaking down over the loss of his first son — but he pressed on.

The change in “Be Mine” is that Frank’s observations are more persistently downcast, as he — but Ford, really — struggles to build up a head of steam around what he observes. (That was also an issue with the janky linked stories in the fourth Bascombe book, 2014’s “Let Me Be Frank With You,” but he had a Forever War and Hurricane Sandy to work with.)

Now Frank is obsessed with happiness and unsure if he’ll attain it. He suspects he’s always the butt of a joke — from his snarky son, from the unctuous staffers at the Mayo, from the woman renting him an RV for the Rushmore trip. (Said RV is named the Windbreaker, another joke.) “If three house moves are the psychic equivalent of a death, a son’s diagnosis of ALS is equal to crashing your car into a wall day after day, with the outcome always the same,” he laments.

The novelist perhaps most associated with Brooklyn lives in Claremont and has a delightful new dystopian novel out, “The Arrest”

Not much happens in “Be Mine” in terms of plot — it’s a straight drive west to Rushmore — and what does happen is marinated in Frank’s bemusement and ambivalence. He observes protesters at a mall complaining about Valentine’s Day in a feeble attempt to satirize a woke mob (“VALENTINES DEMEANS WOMEN AND LOVE”); witnesses a hostage situation and a bad accident; visits a casino; and arrives at his destination.

The presidents chiseled in the rock are smaller than expected, and less likable (“None of these candidates could get a vote today — slavers, misogynists, homophobes, warmongers, historical slyboots, all playing with house money.”) Bascombe’s America circa February 2020 is more uncertain, and Frank is less on top of it. He sees an RV with both Biden and Trump stickers, “to be on the safe side.”

This wishy-washiness is Frank’s problem, but also the novel’s. “Be Mine” lacks the forward thrust of the first two Bascombe novels — both classics, however gassy. And it’s all the more frustrating because there are moments throughout the book where Frank’s status as a world-class observer is fully, delightfully intact. The book is studded with pitch-perfect observations of shabby-tacky American everydayness: a hospital waiting room (“non-aggressive paneling, tasteful, nearly-good plein air wall art”), a casino (“an elevated bank of TVs above a taxidermied wolverine doing combat with a taxidermied coyote over a taxidermied rabbit”); Donald Trump (“tuberous limbs, prognathous jaw, looking in all directions at once, seeking approval but not finding enough”); life itself (“ants scrabbling on a cupcake”).

Over five years, I read 1,001 novels to hear the voices that fill this country. These books showed me that the places of American fiction can’t be divided into blue or red states.

Early Bascombe novels were overrun with lines like those; now they’re relatively starved for them. A 70-something man ground down by divorce and loss shouldn’t be expected to be in good humor, of course. But it’s not unreasonable to expect fiction to be a lively guide into that feeling of being ground down. Frank tries. Ford tries. But mostly Frank is driving down a straight line in barren prairie land, heading toward his inevitable fate.

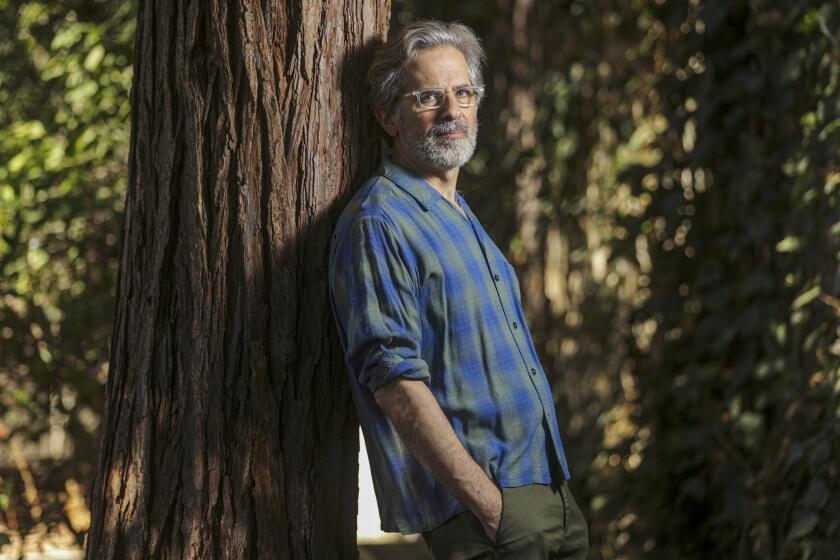

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and the author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.