Swapping bar stories with books impresario, author and proud ‘Dirtbag’ Isaac Fitzgerald

- Share via

On the Shelf

Dirtbag, Massachusetts: A Confessional

By Isaac Fitzgerald

Bloomsbury: 256 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There was a time when you could walk into Zeitgeist, a notorious dive bar in San Francisco, and be certain to see Isaac Fitzgerald jovially drinking there — and, some time later, working the door. As he writes in his memoir “Dirtbag, Massachusetts,” he fell in love with the place; it became home. After a rough-and-tumble childhood, he’s gone much farther (Myanmar), fringier (porn) and fancier (boarding school), always creating newfound families.

These days, Fitzgerald is best known for appearing on “The Today Show” recommending books. Not long ago, he co-hosted the Twitter talk show “AM2DM” with Saeed Jones and was books editor at Buzzfeed. His Substack newsletter, “Walk It Off,” features long ambulatory conversations with authors he’s befriended over the years. Unifying these endeavors is a sunny public persona, a dramatic contrast to the poverty, neglect and violence that characterized part of his childhood.

I talked to Fitzgerald about his book in New York City. We started out with a ride on the Staten Island Ferry — he likes boats about as much as he likes bars — on a stunningly perfect day. The ferry passed so close to the Statue of Liberty that I could see her gold torch glow in the sun: a million-dollar view. “This is free!” Fitzgerald exclaimed, and then exclaimed again, because it is astonishing and true, and because his exuberance is real.

My plan was to interview him over drinks in the borough of Staten Island. The result would be a beer-by-beer diary of our (edited) conversation. Not surprisingly, the plan took some unexpected turns, as bar stories tend to do.

The author of ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ and a new essay collection explains the ‘woman problem’ embedded within L. Frank Baum’s ‘Wonderful Wizard of Oz.’

Beer 1

Location: Steiny’s Pub

Isaac Fitzgerald: Let the record show that I have had one Johny Bootlegger Fruit Punch on the Staten Island Ferry. I am starting a Budweiser, but for openness and honesty, I also had one beer before I arrived at the Staten Island Ferry. So this is technically drink three, beer two.

Carolyn Kellogg: And I had most of a Miller Light tallboy. You took some atypical paths before becoming a proselytizer for books at Buzzfeed and now “The Today Show.” What did you like so much about books that you wanted to make a career of publicly touting them?

IF: I did come to this life a bit differently than the average. I had a very interesting, unique childhood, but I would be a liar if I did not say that one thing my parents instilled in me at a very young age was a love and respect for books, and with that, education. Books were an escape hatch, portals to another universe.

I view it as a calling. Because I still believe! I don’t still believe in Santa Claus, I don’t still believe in a lot of different things that I was raised with, but I really, really, really do believe in the power of books.

CK: I’m sorry for what you went through when things were bad. How did you make choices about what to write about your family experience?

IF: It’s an interesting thing: I, for a very long time, would talk your ear off about how I was not going to write about my childhood. I came up in the ’90s and 2000s; there were a lot of books by oftentimes straight cis white men that were like, “Woe is me, my childhood was so bad.” And I was like, those books are done. Sometimes you’re hypercritical of the things that maybe you do actually want to do. Then as I sat down to try and write this book — and essays that were published before the book even became a thing [“Confessions of a Former Former Fat Kid,” “The True Story of My Teenage Dirtbag Fight Club”] — I hadn’t gone to therapy yet. I hadn’t figured those things out yet. So I kept going back to this box. It took many, many years. There were many deadlines blown. I kept trying to write something else instead of what the book needed to be.

Beer 2

Still Steiny’s

CK: Sometimes in a memoir people talk about their accomplishments. And you don’t?

IF: [Laughs] Oh, that’s the first time anybody’s asked me that question. To your point, there’s no Buzzfeed, there’s no McSweeney’s, there’s no Rumpus. That was a choice. Once I realized that my childhood world is going to be the core of this thing, I realized the story I was looking to tell. And I knew if I’d gotten to a lot of those other things, it would become a lot more complicated.

CK: But you did write about doing porn, so it’s not just childhood.

IF: That’s a good point. But to answer your question, essays that are like, “Look at how good I am,” I think are the boringest things on the planet.

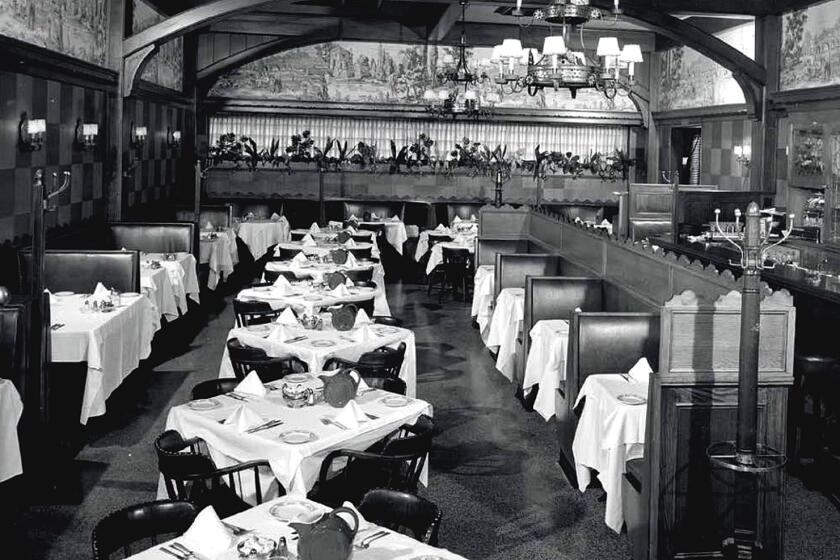

L.A. transplant Stanley Rose’s short-lived 1930s bookstore and boozy backroom became a literary haven for Chandler, Fante, Faulkner, West and many more.

Some more beers ...

This is where my plan started to fall apart. At one point Fitzgerald relayed an important anecdote about something he’d read and been moved by when he was younger, and then I discovered that my recorder was off. Rounds were ordered but not logged. As if in tribute to Fitzgerald’s home turf, Boston’s ’70s anthem “More Than a Feeling” blared over the bar’s speakers.

I tried to ask him about his sections on going to boarding school, in which he makes friends, discovers class distinctions and gets into less trouble than he did at home. He was as frank over beers as in his writing about masturbating together with his classmates but steered the conversation away from his time working in porn. He was part of the early alternative video scene from San Francisco produced by Kink.com; he said he’ll defer on that subject to the writers and activists who’ve stayed involved with that industry.

At some point I dragged us to another bar so I could eat some food.

Beer 4? 5?

Cargo Cafe, which serves nachos

CK: There’s a great love of one particular bar in your book. How did you boil all your stories down into a single place — and a single narrative?

IF: Just for the record, Zeitgeist is my white whale, and this essay is just the tip of the iceberg. My joke that I say — that’s not a joke at all — is that I learned how to write so that I can figure out how to tell the story of Zeitgeist. The essay in the book is about me loving bars as places of community and as places of family.

What makes it such a wonderful story is, just as a space, it’s joyous and it’s gone through all these iterations. It was a gay bar. Then it becomes a really serious motorcycle bar. Then it kind of becomes almost a joker motorcycle bar. Then it becomes a hipster bar. You can still see that there are these people that are finding their freedom there, that are figuring things out, what it means to live their life.

CK: What makes a bar story different from other stories?

IF: Bar stories and fables for me have a lot in common. There’s usually a lesson, but at some point an animal is talking. [laughs] This is not journalism — but there is a truth to it. I also think a bar can be a place where people can be their most honest selves. Now whether that’s the alcohol, whether that’s, “Hey, you’re a stranger, I won’t ever see you again …” There’s something about the — I’m not gonna come up with the word here, something like the tide — people are rolling, they’re rambling. A bar story lends itself to a little bit of interpretation and that’s what I love about it.

Greg Ginn started a record label that brought the world Sonic Youth, Hüsker Dü, the Minutemen and more. A photo book and a deep history tell his tale.

Kellogg is a former books editor of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.