Review: In 1982, an artist snooped on hotel guests. Decades later, it’s a mesmerizing book

- Share via

On the Shelf

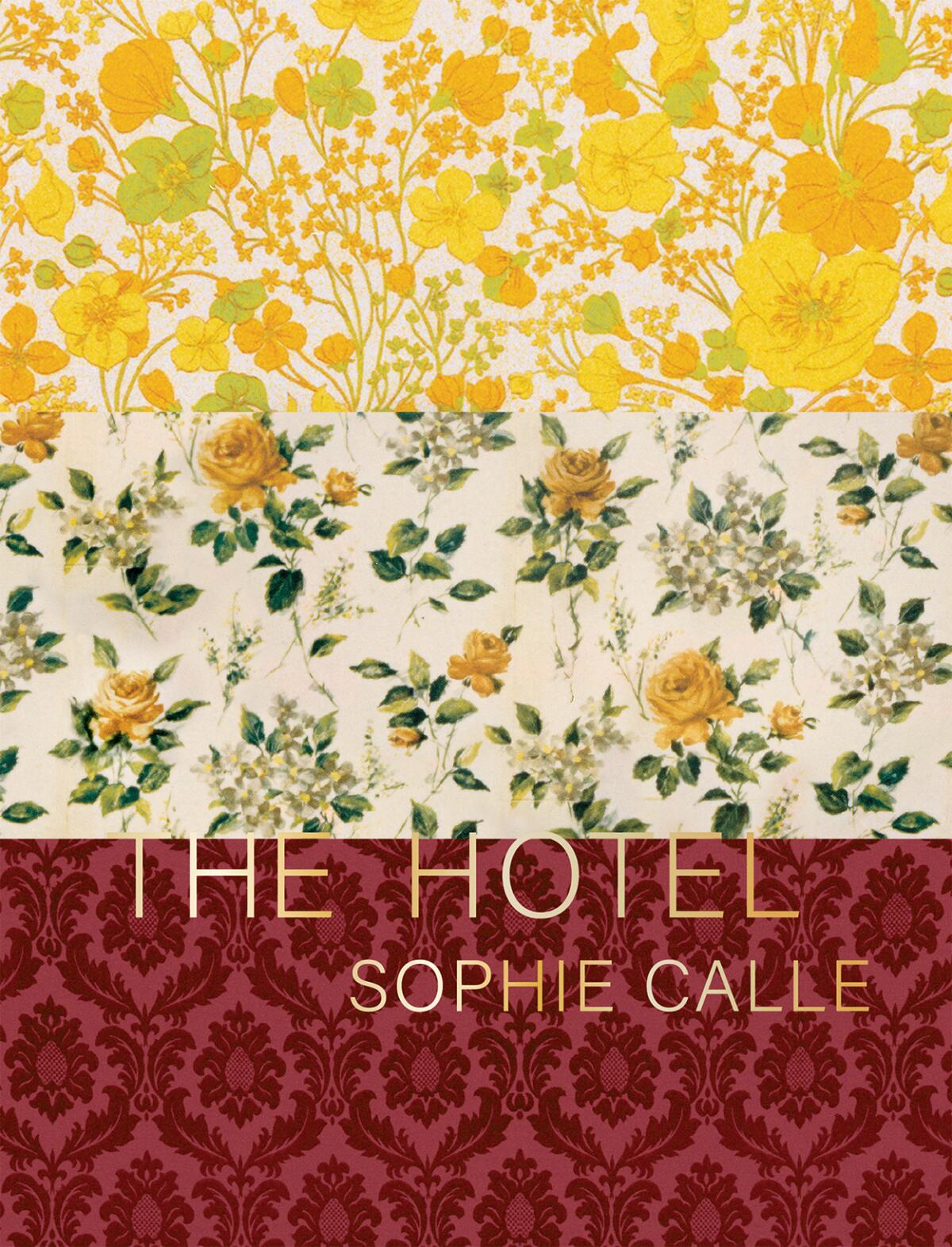

The Hotel

By Sophie Calle

Siglio: 248 pages, $40

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

For Sophie Calle, art is provocation. This applies to both the artist and her audience. In a career spanning more than 40 years, she has blurred the lines between observation and intrusion, documentary and narrative, producing books, films, installations, interventions. “The Hotel,” her most recent work to appear in English, represents a case in point: It’s a book that records an ongoing process of surveillance, in which Calle “was hired as a temporary chambermaid for three weeks in a Venetian hotel. I was assigned twelve bedrooms on the fourth floor. In the course of my cleaning duties, I examined the personal belongings of the hotel guests and observed, through details, lives which remained unknown to me.”

Like much of Calle’s work, I’d suggest, such a project has roots in the Situationist ethos of psychogeography. But she is less interested in displacement than complicity. Such was the case in her 1994 installation “Phone Booth” (1994), in which Calle outfitted a Manhattan callbox with food, paper and other amenities, then recorded the reactions of those who randomly encountered it. That piece was inspired by the novelist Paul Auster, who urged Calle to “pick one spot in the city and begin to think of it as yours. … Take on this place as your responsibility.”

Two more obvious antecedents are the books “Suite Vénitienne” (1981) and “The Address Book” (1983), which flip intimacy on its head. In the first, Calle follows a man identified only as Henri B. from Paris to Venice, where she pursues him for a dozen days. In the second, Calle photocopies an address book she has found on a Paris street and interviews the contacts about its owner, Pierre D.

The books represent a pair of oblique portraits, but even more, they raise discomforting and irreconcilable questions about curiosity, privacy and art. The result is work as curated as it is invasive, collage portraits that reveal as much about Calle and her obsessions as they do about Henri B. or Pierre D. “Pierre, I have ‘followed’ you, ‘searched for’ you, for over a month,” she acknowledges at the end of “The Address Book.” “If I ran into you on the street, I think I could recognize you, but I would not talk to you.”

“The Hotel” operates as something of a companion volume to these books; like “Suite Vénitienne,” it was made in 1981 in Venice, and like “The Address Book” it relies on bold, at times dizzying acts of exposure and inquiry. Its set-up is very much in keeping with Calle’s aesthetics: so apparently matter-of-fact, so simple — yet encoded with overlapping layers of complexity.

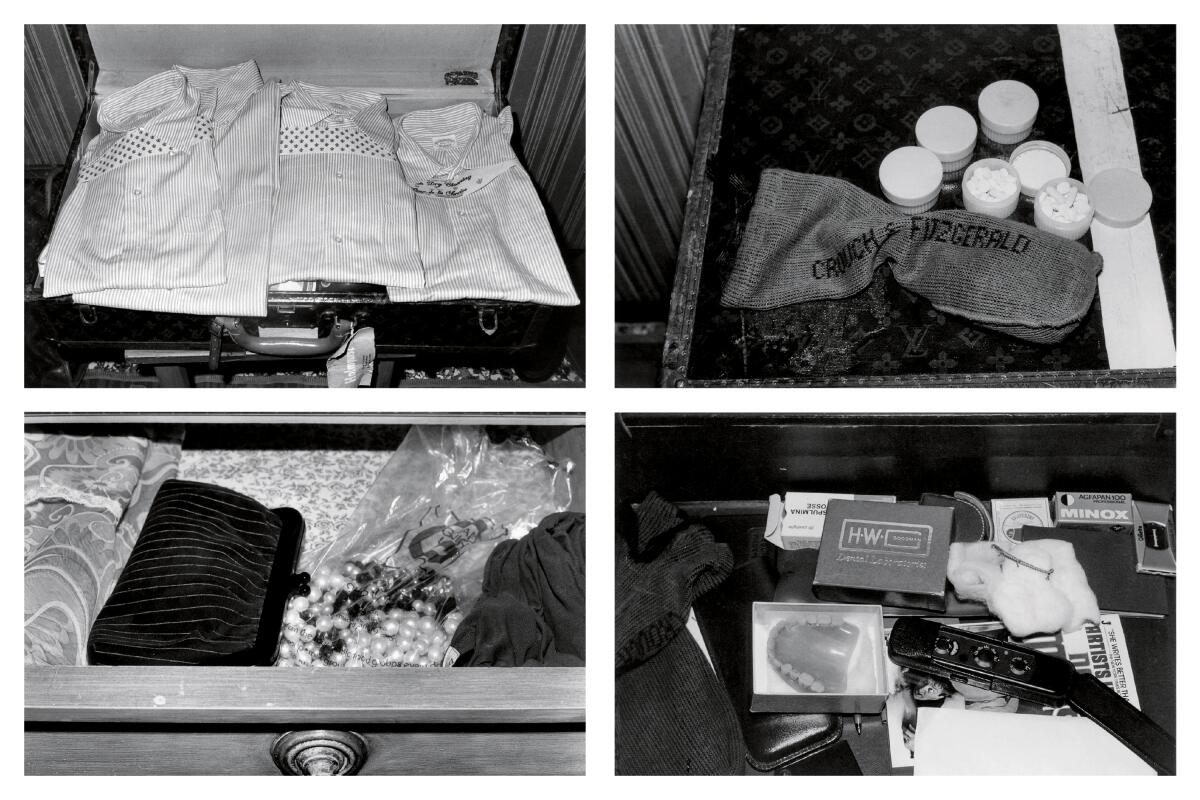

On the one hand, Calle is there to do a job; those 12 rooms are (to appropriate Auster’s term) her responsibility, and throughout “The Hotel,” she participates in the dirty work of cleaning, changing sheets and making beds. On the other, she uses guests’ perfume and rifles through their belongings, annotating her experiences in a clinical yet escalating log.

In a city that gets conflated with fantasy, the late writer’s work gave permission to honor the details of everyday aesthetic experience.

In one room, she compares the clothes in a male guest’s closet against a packing list she has also found. “By elimination,” she explains, “this tells me that today he is wearing blue trousers, a blue T-shirt, and a windbreaker.” When, however, the man returns as she is cleaning, “dressed in the way I thought,” Calle can’t help but be disappointed. “[H]e is about twenty-eight,” she reports, “with a weak face. I will try to forget him.” It’s as if Calle wants us to consider the tenuousness of our own connections, to remind us that we are always constructing or reinventing the people in our lives.

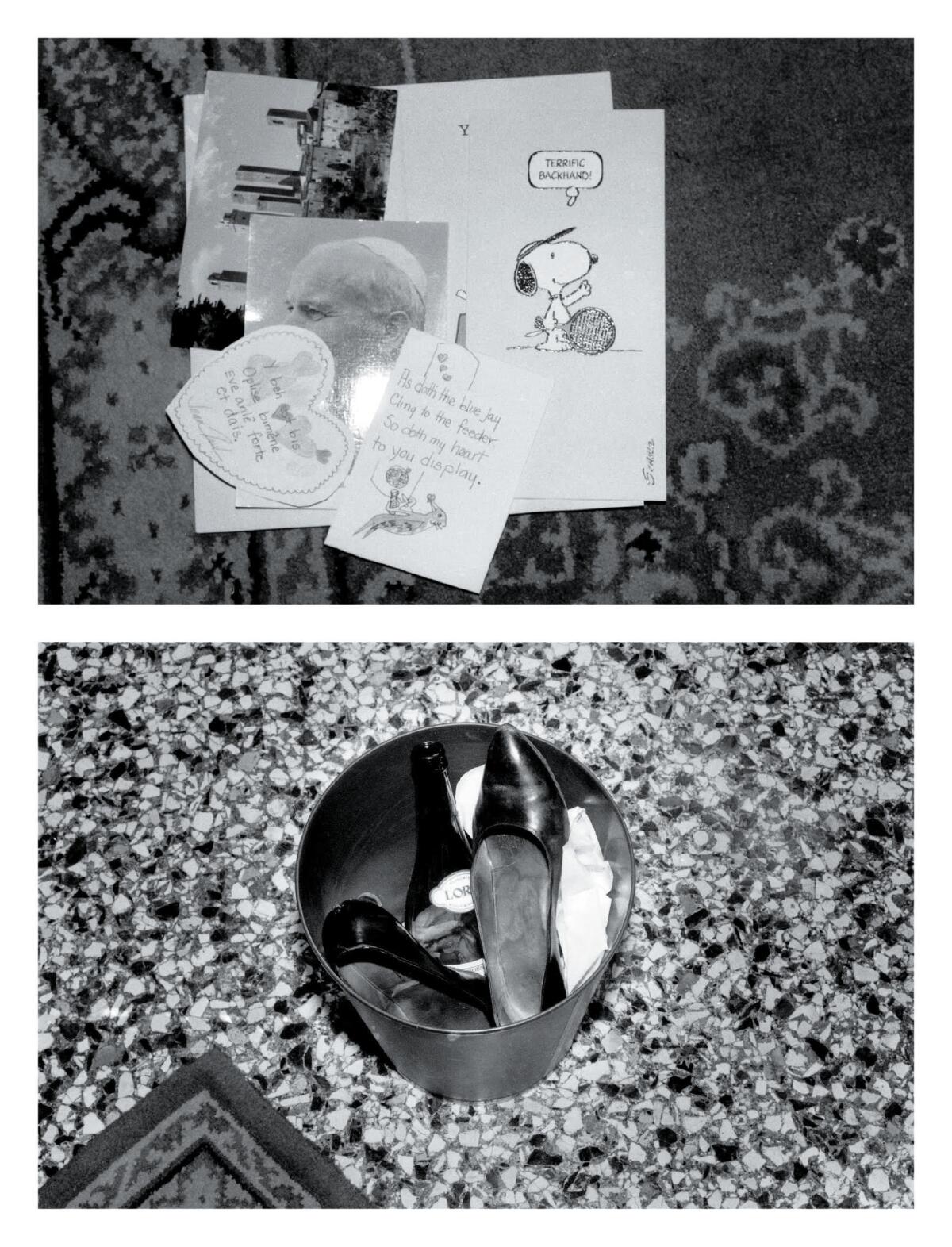

The key to Calle’s intrusions is that they are passive but also active, which means that she is at the mercy of the evidence she finds — the books, the medications, the wardrobes — while also imposing herself as both observer and participant. Of an early intervention, she writes, “The twin beds have been slept in. In the waste basket, the banana peels, a bottle of water, and a pair of hardly worn flat black heels (they fit me; I take them).”

On the facing page, we see a black-and-white photograph of the shoes.

Both text and image here are so offhand we almost overlook them. Still, the implications are profound. Did Calle really take a pair of shoes? Is it theft if the shoes have been discarded by a guest? This conundrum is representative of Calle’s larger narrative, which doubles back on itself, erasing and revising, not least because the rooms to which the artist keeps returning are always inhabited by another set of guests.

Calle makes this explicit in the patterning of “The Hotel,” which eschews chronology in favor of bricolage. The book comprises a series of sequences that detail her exploration of every room. These generally feature a few short prose entries and an array of photographs. As she did in “The Address Book,” Calle often inserts the images out of order, before or after the texts that will explain them, destabilizing our sense of structure and of time. She further highlights this by arranging the sequences nonconsecutively; “It’s my last day of work at the Hotel C.,” she writes in an early passage. “I leave it up to my successor to observe the variations of the pillows in Room 28.” Six pages later, we return to the start of her employment, with an entry dated Feb. 16.

For more than 30 years now, Sophie Calle has engaged in art as provocation; her 1983 project “The Address Book” begins with the discovery, on a street in Paris, of an address book, which she then uses to excavate the life of its owner, contacting everyone within.

The effect is to make time static, as in a hotel. We stay for a few days, for work or an occasion; it is a willful withdrawal from our daily lives. Nonetheless, we have no choice but to bring those lives with us, in what we pack and carry, what we leave out on display. For Calle, this creates opportunity; as she steals chocolates, reads postcards and journals, and catalogs bedside reading materials, we begin to see her subjects, but not entirely — more a set of glimpses from the corner of an eye.

We are always aware that the people whose belongings we’re observing exist beyond these pages, even as they remain out of reach. As if to emphasize the point, the book itself is lush and artfully designed, with gilt-edged pages and a cloth cover that resembles the wallpaper in each room. The images include color still-lifes (Calle is especially drawn to beds, made and unmade) and exude a kind of photorealistic starkness, as if portraying a crime scene.

The point is that we never really know anyone except via the surfaces, that we are telling stories to ourselves. We define one another through our assumptions, based on what we read or wear or eat. Even in a space as intimate as a hotel room, the essential distance of humanity remains. “The room is empty,” Calle writes of one anonymous encounter. “Gone at last. I air out the room and change the sheets.”

As to why this is compelling, there’s a voyeuristic aspect; we are curious about how others live. Yet more essentially, it’s a matter of our transience, the fact that we will all eventually disappear. What we leave behind is largely detritus, the bits and pieces Calle preserves. The paradox is that even as we peruse the scattered evidence she gathers, her subjects continue to elude us. Or maybe that’s the whole idea.

Ulin is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

The best of the year’s TV shows, movies, music, games, theater, art, architecture and more.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.