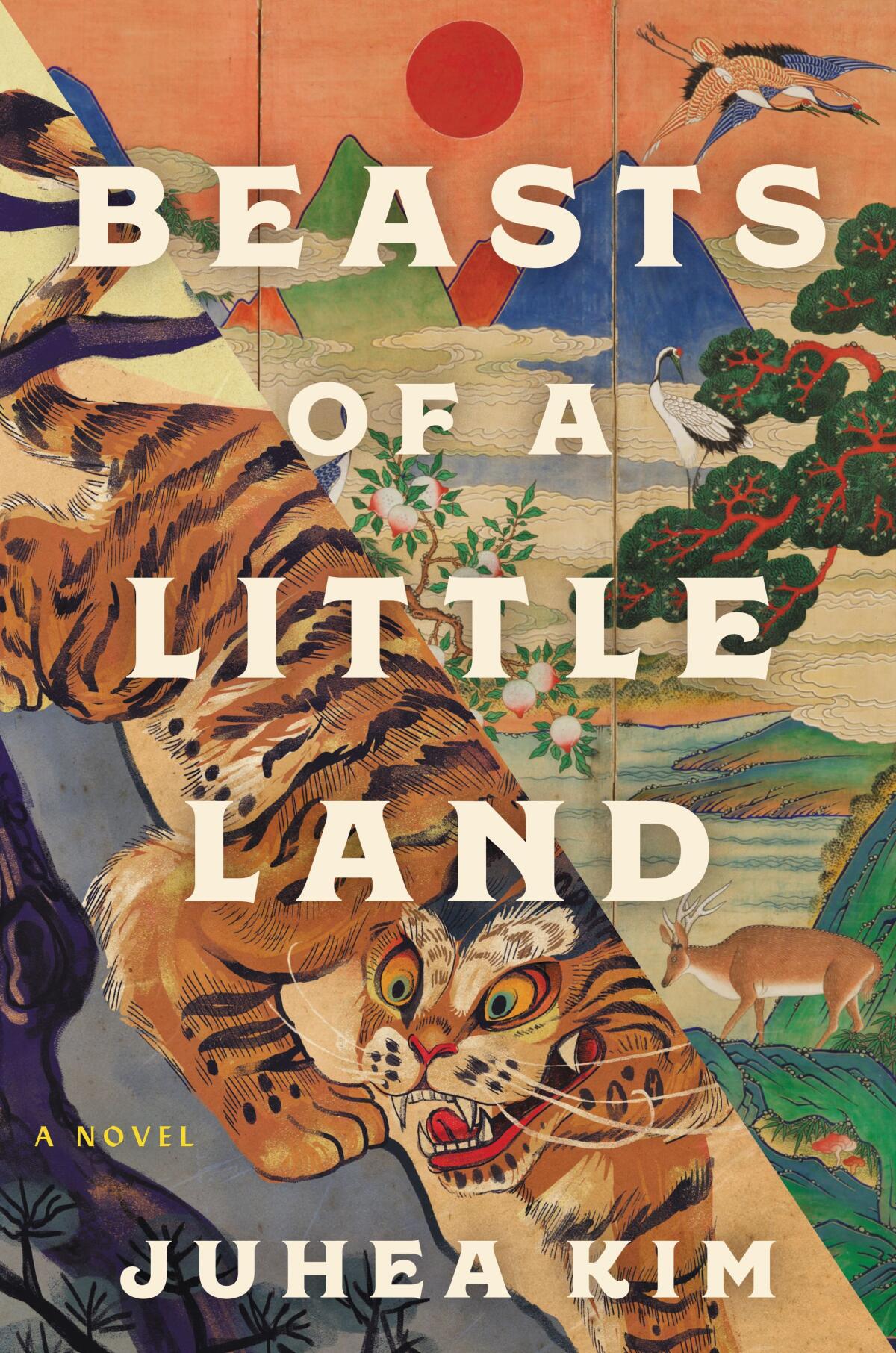

Review: A debut novel strives to capture the paradoxes of Korean history

- Share via

On the Shelf

Beasts of a Little Land

By Juhea Kim

Ecco: 416 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

You there, with your K-beauty serums, your opinions on the “Squid Game” finale and BTS mania: Do you really know anything about Korea? About its civil war, its colonization by Japan, its enduring economic insecurities?

For the record:

9:09 a.m. Dec. 22, 2021A character cited as “a man known only as Nam” in an earlier version of this review is named Nam KyungSoo. He was not stalking a tiger, as in the original version, but a leopard that turns out to be a tigerling. Later, he chases away the tigerling’s grown mother, not the tigerling. The review also described “a book teeming with brothels and game parlors.” There are no game parlors in the novel and much of the activity takes place in courtesans’ homes, not traditional brothels. In addition, garakji-style rings were not always made in pairs; the ring in the novel was not.

Luckily for you, a number of novels glean this history via absorbing, sweeping narratives. Min Jin Lee’s terrific “Pachinko” (2017) covers a lot of historical ground and doubles as a primer on the Korean experience during World War II. And Juhea Kim’s debut, “Beasts of a Little Land,” strives for even greater scope, beginning during an impoverished 1917 winter and following its characters into the mid-1960s, which are somehow just as bleak.

Fittingly (perhaps too much so) for a novel about a divided country, “Beasts of a Little Land” brims with oppositional pairs. In rough order of appearance: Hunter versus tiger, Korea versus Japan, rich versus poor, parents versus children, man versus woman, sister versus sister, capitalist versus communist, mother versus courtesan … and so on. It’s a great deal to process, let alone rank. Suffice it to say that Korea contains many of these dualities and paradoxes — though, unfortunately, Kim can’t always hold her fictional tiger by its tail.

In that bleak 1917 winter, a man named Nam KyungSoo, on the very edge of starvation and hypothermia, stalks what he believes is a leopard in the wild north, hoping a clean kill will feed his family for a few years. In fact it is a tigerling, whose mother soon becomes a mortal threat. In short order, the tiger becomes a symbol of a unified Korea — elusive, sustaining, insatiable. Nam’s father has told him, “Never kill a tiger unless you have to…. And that’s only when the tiger tries to kill you first.”

Novelist Min Jin Lee discusses leaving her legal career, expressing Asian pride at a time of hate crimes, dealing with people whose stances you dislike and working to change the world, five minutes at a time.

Nam will win that battle, but just barely, and with ramifications for his family for generations to come. He will be discovered, near death, by Japanese occupiers — but will save them from an attack by the grown tiger. In return, the invaders allow him to live. It’s an early lesson in Korea’s tricky navigation of both internal divisions and foreign powers.

To draw from another of Kim’s dichotomies, if the tiger chase unleashes the novel’s masculine energy, its feminine power derives from a brothel. This is where a 10-year-old girl named Jade begins training to be a giseng, or courtesan, after her impoverished family decides it has too many mouths to feed. The courtesan school’s breathtakingly beautiful owner, known as Silver, has two daughters, Lotus and Luna, who will become Jade’s lifelong friends. The young trio migrates south to Seoul and the home of an equally beautiful but much more modern courtesan, Dani.

Another new resident of Seoul in 1918 is Nam JungHo, carrying his father Nam’s only treasures — a silver cigarette case and a silver ring. Like the tiger, these are not mere objects but symbols. The silver ring, we learn much later, is in the garakji style, a type of wedding band with a curved surface that was often made in pairs (though Nam’s was not). A married woman was meant to wear one and keep the other to inter with her husband on his death. It is also associated with Korean national pride, with roots in the Joseon dynasty.

Meanwhile, the elegantly engraved cigarette case, given to Nam père by Yamada, the officer he had saved from the tiger, is an object foreshadowing the foreign forces that will tear apart both the country and Kim’s protagonists. (Dani, for instance, will be courted by a Communist supporter and his rival, a Korean Nationalist.)

Throughout the novel, observations about world politics remind readers of that greater history. “You see, the absorption of a weaker nation … is not only inevitable, but desirable,” says a Japanese general named Ito. “Without Japan, how could Korea have modernized?” These observations come mainly from men, but the women are affected too, especially in their efforts to keep their loved ones fed and clothed.

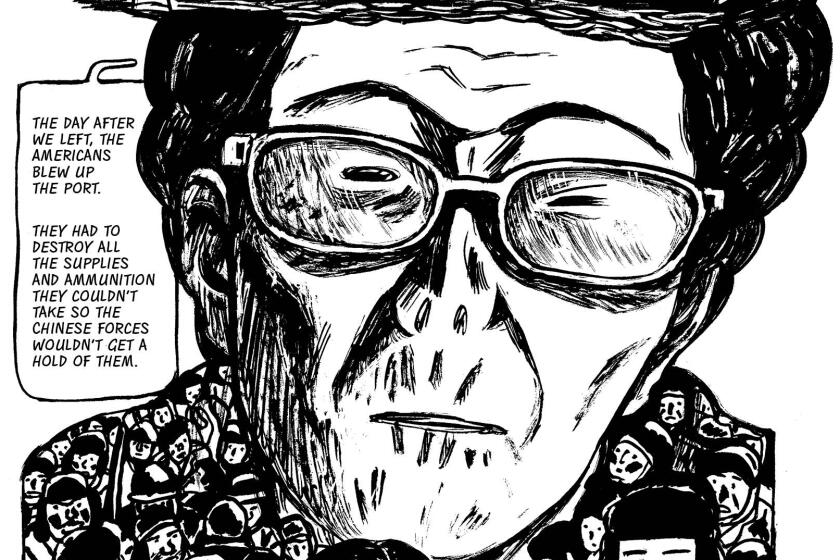

In ‘The Waiting,’ Keum Suk Gendry-Kim fictionalizes a rupture in her own family and so many others in Korea -- loved ones left behind in the North.

Yet there is something jarring in the more personal stories. Kim’s sheen of romance, sentimentality and even a strangely dissonant nostalgia (given the subject matter) might be attributed to the secondhand nature of these anecdotes, at least as the relatively young author might have heard or read them. When, for instance, Silver’s daughter marries an American Embassy employee, the church wedding scene feels straight out of some grandmother’s diary: “Even through her veil, the bride was so lovely that she seemed to cast her own light,” and the guests “had not known that a woman’s beauty could be so edifying.”

Adding to the sense of unreality is the utter lack, in a book teeming with underworld activity, of any courtesans catering to (or anyone having) preferences other than the heterosexual.

Yet that is a small quibble next to the strangest omission in the book — its jump from 1945, when the Japanese emperor surrendered to the Allies to end WWII and Korea declared its independence, to 1964, when the lives of several characters finally end. What happened to the brutal war that resulted in Korea’s schism? We have bits of foreshadowing, especially in the story of Kim HanChol, who works his way up from Jade’s favored rickshaw driver to car manufacturer.

Perhaps Kim plans a second novel that will cover the decades missing from “Beasts of a Little Land.” Or perhaps those years were too difficult, too muddled, to grapple with. Should she take on the thornier moments of history — Korean or otherwise — the author would do best to push past shimmering symbols and easy archetypes into a reality far messier than we might prefer it to be.

Perhaps Kim’s ambition has gotten the best of her story, reducing what she aimed to amplify. Next time, she might ease up on the narrative’s throttle and allow her frequently complex and interesting characters to take control.

For novelist Steph Cha, K-pop band H.O.T. and action film “Shiri” are a few culture predecessors to this hallyu moment of global success for “Parasite” and BTS.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.