Pushing to close the funding lag that drains millions from homeless services

- Share via

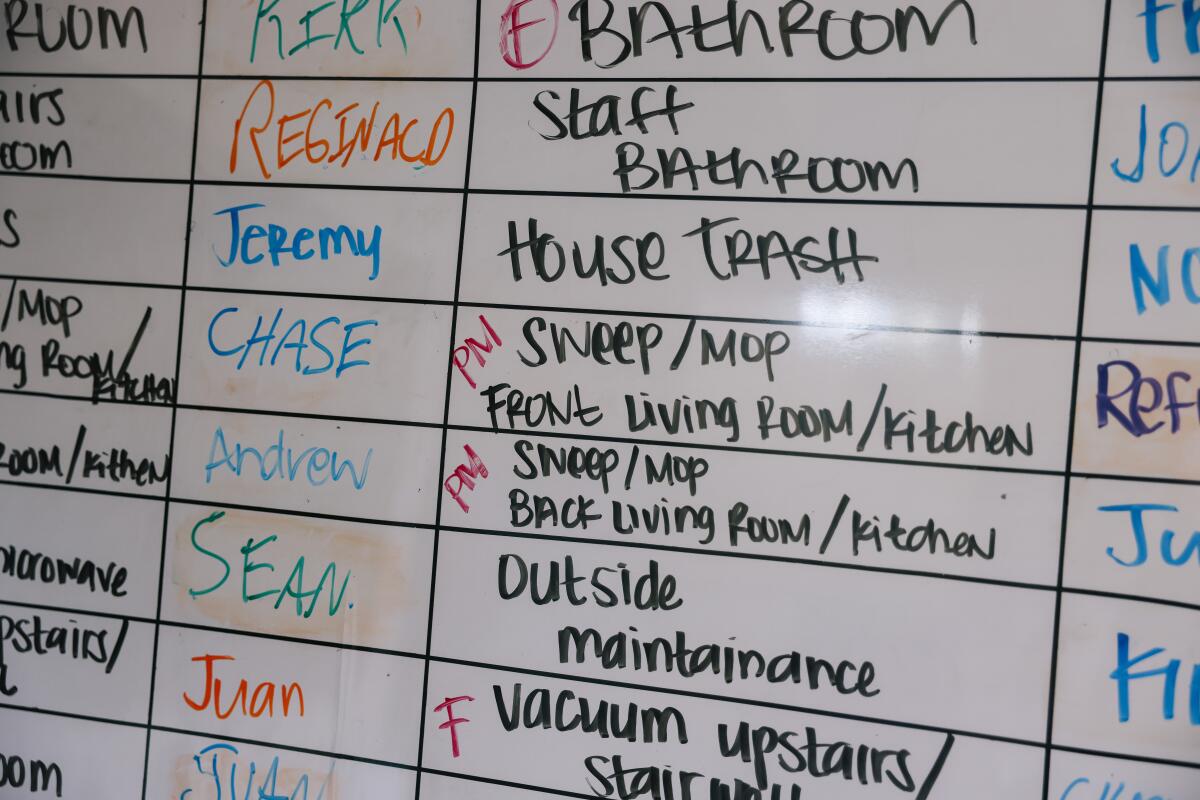

It was June 7, payday at Reclaim-Possibility, a 22-bed home in South Los Angeles for men released from jail and prison who might otherwise fall into homelessness.

Once again, owner Kalain Hadley had to tell his 10 employees they might not be paid.

Reimbursement checks due on the first from his funding agency, Amity Foundation, had not arrived.

“It’s just really not a pleasant conversation,” he said.

Like many nonprofit providers with government contracts, Hadley is in perpetual arrears due to a tangled reimbursement scheme that ties up payment for 60 to 90 days after he bills for services.

Invoices based on his head count, which varies from week to week, go to his two funding nonprofit agencies — Amity and HealthRIGHT 360 — then on to the Los Angeles County Probation Department and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Payment goes back to the agencies, then reaches Reclaim-Possibility, sometimes by payday, often not.

With rent, salaries and utility costs all constant but payment whipsawing based on the number of clients he has at any one time, Hadley felt he had no option but to go to predatory lenders.

“They give you $30,000. You pay back $43,000 with daily payments, which ends up being something really crazy,” Hadley said.

Advocates believe the number of children living on Skid Row will remain high as families in need of shelter confront a city with insufficient options.

As homelessness related services have ballooned in recent years, that funding lag has become a huge drain on the multibillion-dollar homelessness system affecting hundreds of hands-on providers like Reclaim-Possibility and also the largest organizations.

Testifying before the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors on the crisis last month, John Maceri, chief executive of the People Concern, said that his $85-million operation must carry $8 million in debt to cover the delay from invoice to reimbursement. Money intended for services goes instead to interest.

To alleviate that problem, the supervisors on Tuesday gave the go-ahead to county staff to provide quarterly cash advances from Measure H homeless sales tax proceeds to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority that it can forward as cash advances to its contractors. LAHSA would then reconcile invoices afterward.

But that inflow of up-front cash won’t reach Hadley, whose reimbursements come through the criminal justice system.

Now, an alternative plan to extend a lifeline to Hadley and other hands-on providers like him is arising outside government. It’s a project of Future Communities Institute, a specialty nonprofit that bills itself as an “action-tank” that seeks solutions to complex challenges by gathering academia, government, tech and philanthropy to test-launch new strategies.

Justin Szlasa, director of homeless initiatives for Future Communities, is promoting a targeted solution to get money directly into the hands of small providers like Hadley when they need it.

It’s modeled after factoring, the commercial practice going back into antiquity in which a company sells its accounts receivable — what it’s owed but has not yet been paid — at a discount to get cash in hand.

“Almost every industry has some kind of bridge financing like this that helps smooth things out and makes things work better,” Szlasa said. “And it’s high time the nonprofit sector, particularly for homeless services, has that in Los Angeles.”

Szlasa, a film producer and tech entrepreneur, worked several years as a volunteer, board member then transitional executive director at SELAH Neighborhood Homeless Coalition before committing full time to homelessness at Future Communities, which is fiscally sponsored by the Edward Charles Foundation.

Tasked to work on the funding gap problem, he found inspiration in New York.

“I looked around for other solutions to this problem and found the Fund for the City of New York,which has been working on this for that past several decades,” Szlasa said.

Corporations are building new suburban subdivisions to rent them out, changing how people live and build wealth in America.

Funded by philanthropy and New York City, FCNY has made more than $1.65 billion in no-interest bridge loans since its inception in 1976, recycling the money as loans are repaid.

Szlasa is seeking funds from government and philanthropic donors to create a working capital fund. Unlike factoring, which involves the sale of assets, the fund would make no-interest loans to be repaid when the reimbursements come through.

He has set a modest goal of raising about $650,000 to cover setup and a year of operations to prove the concept and sort out operational details.

“We want to get things up to running and show that operationally this is going to work,” he said. So that “we can make loans. We can provide relief. We can get the money back. And we can set up that infrastructure to provide capacity.”

The cost for a year of operations would be about $450,000, including staff and one-time work to write contracts and set up the loan servicing tools.

“We think the minimum capital you need to show this will work is $200,000,” Szlasa said. “That’s so I can make a $50K loan. I can get paid back and that can start to operate.”

A similar concept is already being tested through a fund created by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation to assist organizations it supports. The Nonprofit Finance Fund, a community-oriented financial institution that manages the program, has so far made 17 loans averaging $480,000. Those loans, to organizations with budgets from $2 million to $50 million, carry no interest but are more similar to conventional loans in the time it takes to get the money out, said Annie Chang, vice president for community engagement.

Szlasa is aiming for a more nimble process that would get money out the no more than three days, especially to smaller organizations.

“Those groups who have the least ability to access a line of credit, like the Kalains of the world,” he said. “That’s the objective to initially help those groups that are really struggling that way.”

Time is of the essence for Hadley, 59, a three-strikes lifer who turned his life around during 25 years in prison, earning a bachelor’s degree before amendments to the law cleared the way for his release in 2014.

“During life sentence, I had an epiphany: If I didn’t make some changes, I would be walking in that 1,000 square feet all my life,” he said.

Since then, he earned a master’s degree in social work and did outreach and counseling for several Los Angeles area agencies before deciding to go into business for himself.

His timing couldn’t have been worse. He opened the first of his two halfway houses in January of 2020, just before the pandemic cut off the supply of clients for several months. He didn’t receive his first reimbursement check until October. To stay afloat, he pumped in his retirement funds and loans from family. And then turned to payday lenders.

He’s been in a hole ever since, and twice recently has come up short on payday.

On the 7th, the crisis passed. The wire transfer from Amity Foundation finally hit his bank account at 3 p.m.

“I rushed to the bank, made a withdrawal and got my employees paid,” he said.

But food and utility bills were piling up, and the lenders were texting him daily with offers.

“I almost took one yesterday,” he said recently. “I’m in the process of paying one I got in February or March. Just because the terms are so ridiculous, I resisted it yesterday.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.