California’s population increased last year for first time since 2020

- Share via

California’s population rose last year for the first time since 2020, according to new state data.

The state’s population increased by 0.17% — or more than 67,000 people — between Jan. 1, 2023, and Jan. 1, 2024, when California was home to 39,128,162 people, according to new population estimates released Tuesday by the California Department of Finance.

“The brief period of California’s population decline is over,” H.D. Palmer, a department spokesman, said in a phone interview. “We’re back, and we’re returning to a rate of steady, stable growth.”

That resumption of growth, Palmer said, was driven by a number of factors: Deaths, which rose during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, have fallen nearly to pre-pandemic levels. Restrictive foreign immigration policies imposed during the Trump administration have been loosened under President Biden. Domestic migration patterns between states also have changed, boosting the state’s population.

In 2021, as the pandemic raged, more than 319,000 people died in California and fewer than 420,000 were born, the data show. Last year, about 281,000 died in the state, while nearly 399,000 were born.

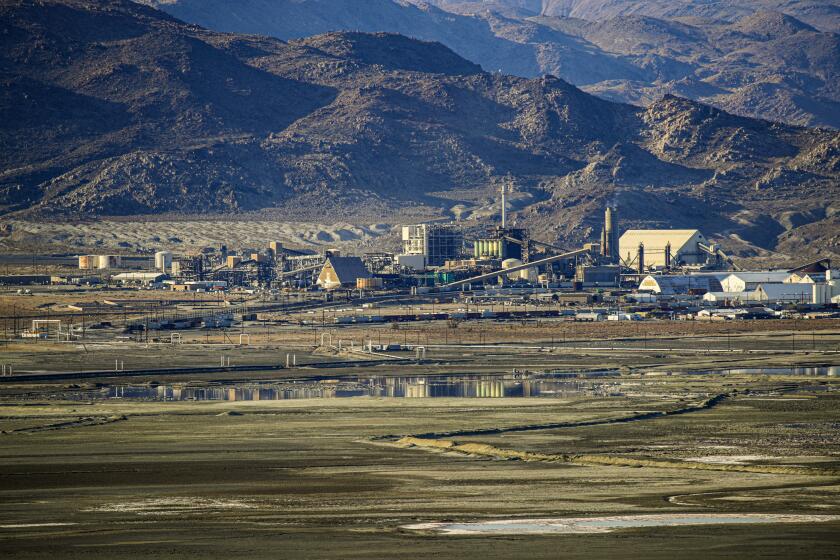

Amid California’s housing crisis, some small communities persist with property values well below the statewide norm.

And while California saw a net loss of nearly 3,900 people to international immigration in 2020 — when many countries’ borders were closed due to the pandemic — the state saw a net gain of more than 114,000 international immigrants last year, according to state data. That’s close to pre-pandemic levels. In 2019, California notched a net increase of about 119,000 international immigrants.

Shifting domestic migration trends — which were the subject of the much-ballyhooed “California exodus” during the pandemic, when remote workers moved to other states where they could live for a fraction of the cost of cities like Los Angeles or San Francisco — also played a key role.

In 2021, about 692,000 people left California for other states, while fewer than 337,000 moved into the Golden State from other states.

Last year, about 414,000 people moved here from other states, while more than 505,000 left for other states. That means California saw a net loss of about 264,500 fewer people to other states last year than in 2021, according to the new state data.

Los Angeles and Orange counties grew last year, though not by much; the former saw a population rise of just 0.05% — or nearly 4,800 people — while the latter notched up 0.31% — or nearly 9,800 people.

For both jurisdictions, that’s a reversal from 2022, when L.A. County saw a net loss of nearly 42,200 residents and Orange County lost about 17,000 residents. The city of Los Angeles saw its population rise 0.3% last year, the data show.

California also saw a net increase of about 116,000 housing units — including single-family homes, multi-family dwellings and accessory dwelling units, or ADUs — in 2023. Palmer described that growth as an “encouraging” sign amid the state’s housing crisis.

That rise, which is a relative drop in the bucket compared with the state’s more than 14.8 million housing units, was led by the city of Los Angeles, which saw a gain of more than 21,000 housing units, followed by an increase of about 5,700 units in San Diego, according to the state data.

While California’s resumption of population growth is a boon for boosters who reject the storyline of the state’s decline, there is no indication that the Golden State will be returning to the massive boom in residents it underwent generations ago.

“For the foreseeable future, we’re looking at steady, more predictable growth that’s slower than those go-go years of the 1970s and 1980s,” Palmer said. “Obviously, there are things that we can’t forecast that could have an impact on our population. For instance, another pandemic.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.