Santa Monica killed a Black entrepreneur’s dream in 1960. Now it wants to make amends

- Share via

The dream of a Black entrepreneur to open a hotel and beach club for Black patrons in Santa Monica in the 1950s was smashed by a racist land grab by the city through eminent domain.

More than 60 years later, the city of Santa Monica is considering repaying the family whose property was seized.

The Santa Monica City Council voted Tuesday to explore compensating the descendants of Silas White, a Black businessman who wanted to renovate an old building on Ocean Avenue into a hotel and beach club for Black patrons in the segregated city.

Santa Monica’s vote comes nearly a year after the city of Manhattan Beach acknowledged its own racist history at Bruce’s Beach, a Black community that was closed in 1924 through official channels. The property was eventually returned to the descendants of Charles and Willa Bruce by Los Angeles County.

In a heartfelt ceremony, Los Angeles County completed the historic land return of Bruce’s Beach by handing the deed to its rightful Black heirs.

The Santa Monica City Council action puts a focus on the city’s history with heightened racism.

A stretch of sand at Bay Street ending at Bicknell Avenue was once referred to derogatorily by nearby white residents as “the Inkwell” because it was frequented by Black beachgoers from 1905 to 1964. A mural that depicts Black people enjoying the sand and sun in the early 1900s is now displayed near that stretch of beach.

Black families who settled in Santa Monica in most cases were fleeing the Jim Crow-era South beginning in the late 1800s. But institutionalized racism followed them and ensured that Black businesses were stymied in Santa Monica and across the country. Beginning in 1922, white homeowners formed the Santa Monica Bay Protective League to shut down a dance hall and block any development by the Black community in the city, according to the book “Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites During the Jim Crow Era” by historian Alison Rose Jefferson.

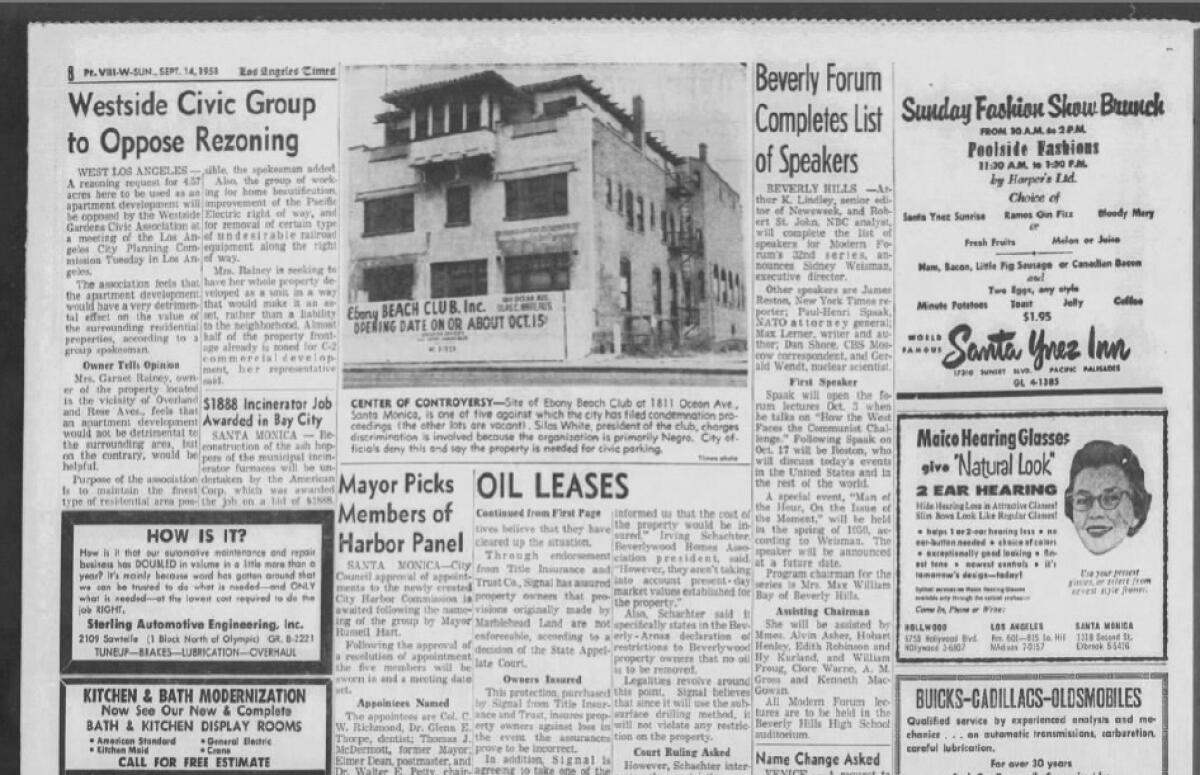

Santa Monica’s own racial reckoning took an important step forward Tuesday to recognize the Ebony Beach Club, a dream location that never materialized. White secured the rights to the building by May 1957, and a buzz started to build around his hotel and club throughout the city and across the county. His supporters included charter member and jazz giant Nat King Cole.

But a few months before White was set to open the Ebony Beach Club, the city launched eminent domain proceedings to seize the property for “civic parking,” according to historical records. A lawsuit followed, but the city won, condemned the property and demolished the building by 1960, replacing it with a parking lot.

Before the building was seized, White placed large signs announcing his intentions to open a club and hotel that would cater to Black patrons in an attempt to ward off theft of the land by the city, Santa Monica City Councilmember Caroline Torosis said before Tuesday’s vote.

“We want to center the needs of the people who have been most harmed by the decisions that government has made,” Torosis said.

City staff will return in 90 days with possible next steps to correct what the city calls “racial animus” carried out more than 60 years ago. That could include the use of eminent domain once again to reclaim property that could be returned to White’s descendants.

Santa Monica Amusements LLC, the company that runs Pacific Park on Santa Monica Pier has announced the sale of the popular destination to an investment firm that plans to put $10 million into the pier’s food and entertainment attractions and general operations.

The city has been in touch with White’s family and the organization known as Where Is My Land, which is dedicated to identifying and reclaiming property taken from Black people. The Ebony Beach Club would have occupied a small portion of the site where the luxury Viceroy Hotel sits today in Santa Monica.

At Tuesday’s council meeting, White’s descendants thanked the council for taking up the issue to explore restitution.

Kavon Ward, founder of Where Is My Land, played a message for the council from 90-year-old Connie White, Silas White’s daughter, who recounted the pain her family experienced when the city stole the Ebony Beach Club from the community.

“Every time I revisit the events that led to my father’s loss of his dream, the Ebony Beach Club, my anxiety and pain returns full force,” she said. “There are no words to describe the anguish of losing the loving communication that we had as a family.”

Chance Davis, White’s nephew, and other family members thanked the council before the vote.

“It is inspiring to see that we are choosing to stand with the Black community and that you are dedicated to righting the wrongs of past councils,” Davis said.

Jefferson, the historian who has documented the Black experience and history in Santa Monica, called the council’s vote “an important step in the healing process for Silas White’s family and the African American community.”

“This didn’t just happen to one family. This was a series of dream-killing exercises in terms of going after African American business development, wealth building and community building,” Jefferson said. “The [city council vote] is another validation of African American humanity and that there were things done to Black people that have inhibited their full citizenship in the region and in the nation.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.