Can homelessness in L.A. ever be ‘rare, brief and nonrecurring’?

- Share via

Earlier this fall, the chief executives of several local foundations gathered at the Southern California Grantmakers offices to discuss expanding their efforts to combat L.A.’s growing homelessness crisis.

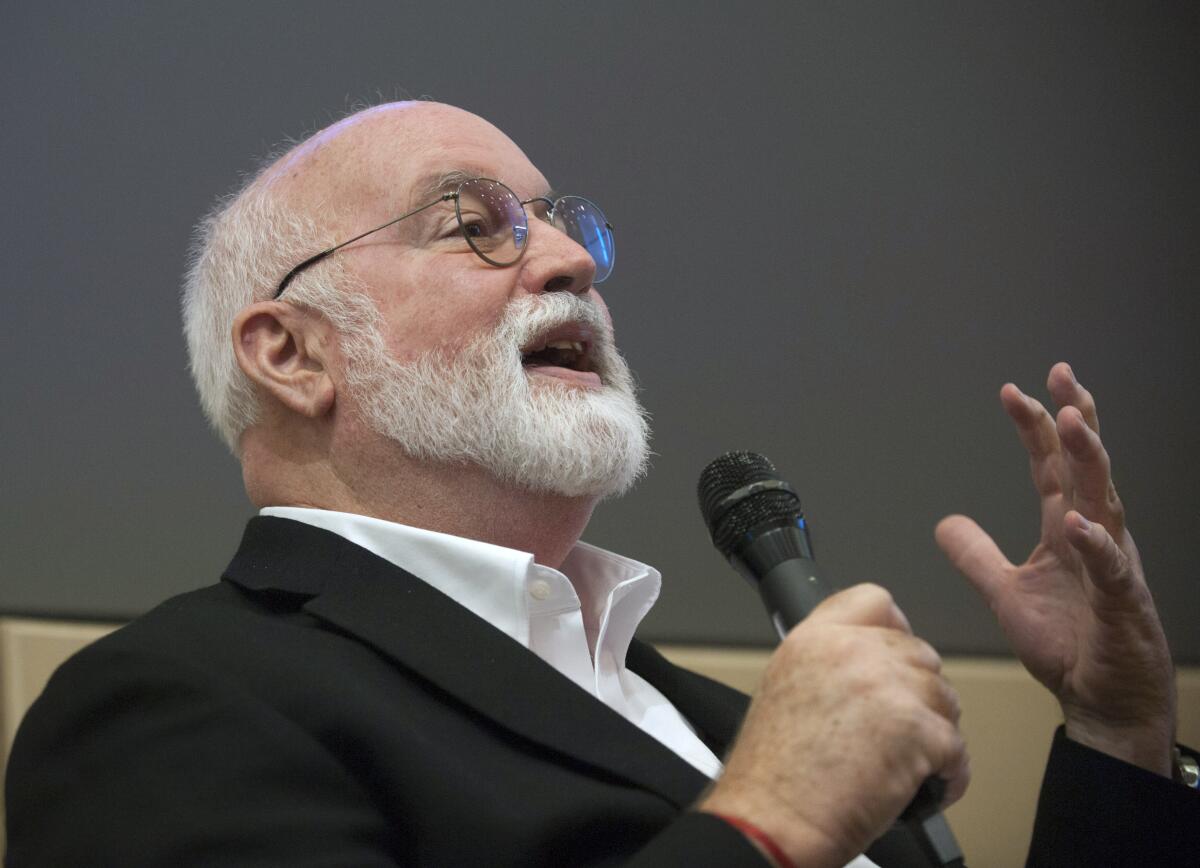

The featured speakers were Peter Laugharn, president and CEO of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, and Elise Buik, president and CEO of United Way of Greater Los Angeles, both fervent believers that homelessness in L.A. can be, “rare, brief and nonrecurring” — a catchphrase among philanthropists deeply involved in housing issues.

The attendees, many of whom had to stand shoulder to shoulder along the walls in the too-small room, stayed for the entire 90-minute meeting.

Wealthy L.A. philanthropists loosen grip on donations, shifting money toward social justice

“It’s easy to be overwhelmed by the scale of the housing problem in L.A.,” says Scott Koch, executive director of Reissa Foundation, a $65-million Santa Monica-based family foundation dedicated to improving the lives of vulnerable populations.

But it “fuels my optimism,” he says, to hear what’s happening on the ground to solve homelessness. Koch sees an “openness” to providing less traditional support, such as construction loan guarantees and direct investments in affordable housing.

Progressive foundations are pushing increasing amounts of money into the hands of the nonprofits working with marginalized Angelenos. But unlike general social service grants for schooling or health, housing funds typically come with strings attached.

The foundations’ generally agreed-upon prescription is for permanent housing with supportive services for all unhoused Angelenos — regardless of a person’s willingness to use those services.

Permanent housing is the solution, says Laugharn, only if it is coupled with “job training, addiction treatment, mental health treatment … for those who want it.”

In June, The Times reported that the latest count, conducted in January, showed homelessness had continued to “rise dramatically,” increasing by 9% in Los Angeles County and 10% in the city of Los Angeles since 2020. It has increased by 70% in the county and 80% in the city since the 2015 count.

“Efforts to house people, which include hundreds of millions of dollars spent on shelter, permanent housing and outreach, have failed to stem the growth of street encampments,” The Times report stated. About 75,500 people countywide were estimated to be living in interim housing, tents, cars, vans, RVs or makeshift shelters.

The crisis has convinced L.A. Mayor Karen Bass to focus on securing temporary housing that’s immediately available to get people off the streets as fast as possible, she told a community meeting of her Getty House neighbors on Nov. 15.

“The city wasn’t looking at this as an emergency,” said Bass. “We are now.”

Foundation leaders say they are sticking with their strategy.

The passage of Proposition H and Proposition HHH—for which United Way led the lobbying effort—has already provided more than $1 billion in public funds to address homelessness, says Tommy Newman, vice president of public affairs at United Way of Greater L.A.

Newman points to Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority data on permanent placements, which show a leap from 14,252 placements in 2017 to 22,659 placements in 2021, a level the county has sustained.

Philanthropic investment in a coordinated approach works, he says.

But it is expensive. L.A.’s Home for Good Funders Collaborative, launched by the Hilton Foundation and United Way in 2011, has provided $70 million for housing with support services, and has expanded from an initial 24 public and private funders to 40 major funders, including the California Community Foundation, the Annenberg Foundationn, the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation, Ballmer Group, and the Weingart Foundation.

Separately, United Way’s independent grassroots network of 23,686 Angelenos has given $31 million to the cause, according to Newman.

The Hilton Foundation has provided more than $270 million for housing in Los Angeles over the last decade, with a commitment to spend an additional $35 million a year until “rare, brief and nonrecurring” reflects reality, says Laugharn, adding: “We’re not in this to provide perpetual palliative care.”

In 2014, in partnership with L.A. County Health Services and other public partners, the Hilton Foundation funded the launch of the Flexible Housing Subsidy Pool, a permanent rental subsidy program for people with complex physical or behavioral health conditions who experience homelessness. Nearly 10,000 people have since received rental subsidies.

While L.A.’s current crop of elected officials appear to prioritize the construction of affordable housing, Laugharn warns that if they fail to act, efforts to end homelessness will fail as well.

An early test of that political resolve may very well be Hope Village, a joint project of the California Endowment’s Dr. Robert Ross and Homeboy Industries’ founder, Father Gregory Boyle.

The vision is for an interconnected community with housing, schools, supportive services, jobs, businesses and green spaces serving formerly incarcerated people, convicted offenders eligible for diversion programs, and their families, says Thomas Vozzo, president of Homeboy Industries.

Work has already started on properties within the two organizations’ neighboring campuses near downtown’s Union Station. But Hope Village needs adjacent public properties and public funding to be fully realized as a safe harbor for a community with one of highest rates of homelessness.

Considering the number of public agencies involved, plus zoning and neighborhood approvals, it could be years before Hope Village is complete.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.