Koreatown grocery store workers protest CEO’s anti-union tactics at conference

- Share via

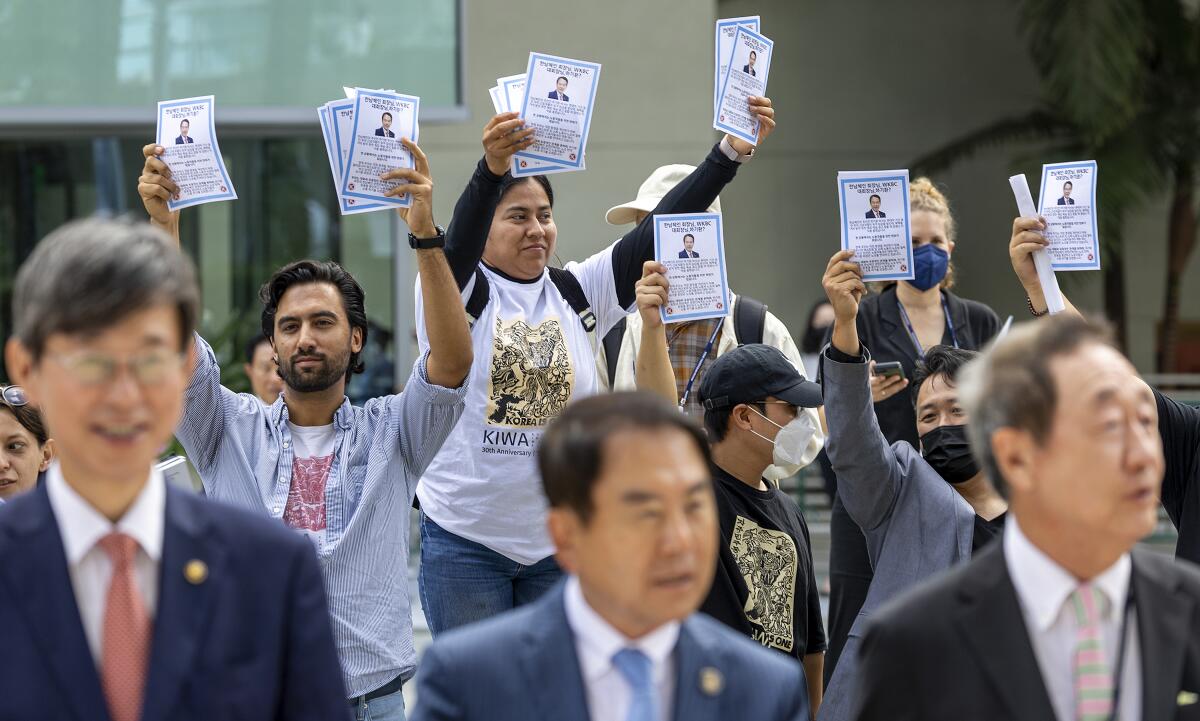

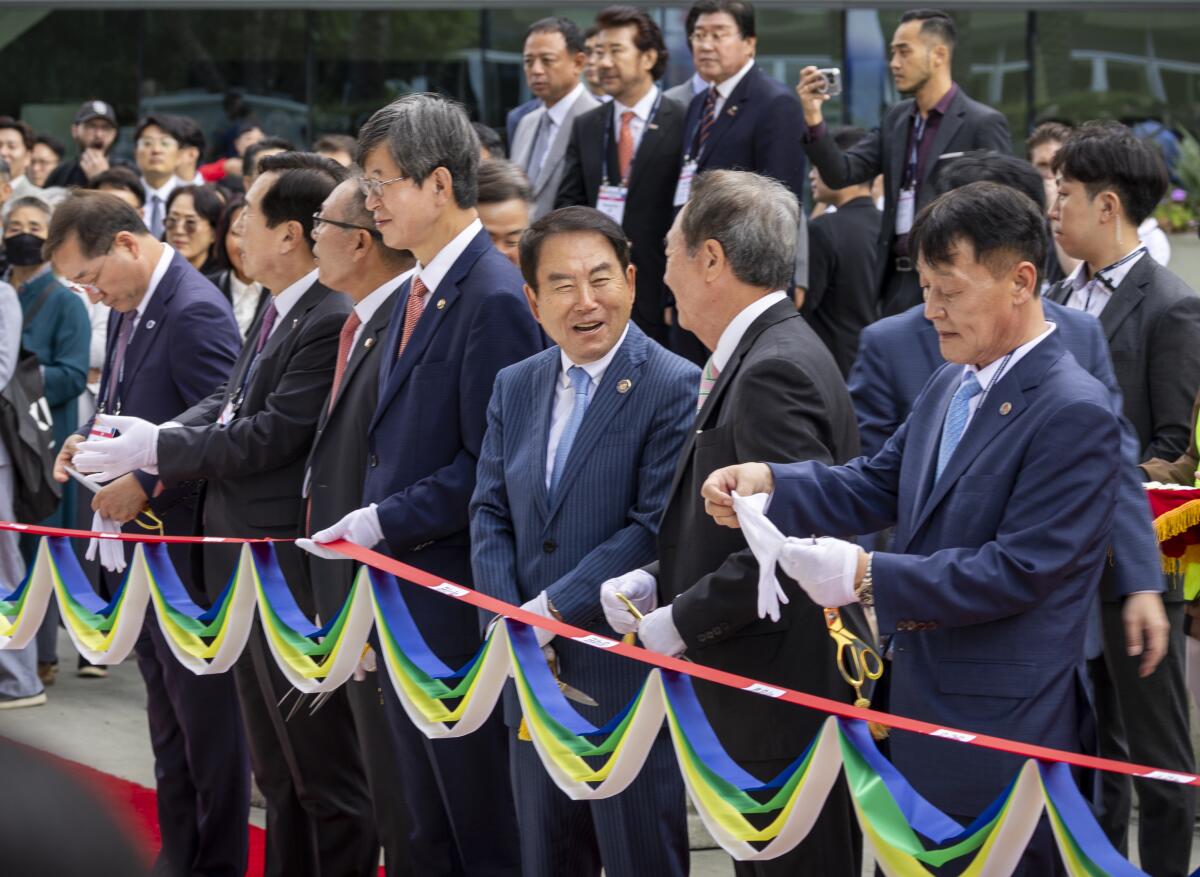

Top executives from some of Korea’s largest companies and South Korean officials posed for a staged press photo on a red carpet at the Anaheim Convention Center recently as a group of protesters quietly moved into the frame.

The demonstrators, most of them workers from Koreatown grocer Hannam Chain and the South Korean air-conditioning giant Coway, stepped onto planters to angle their signs for the cameras. Each pamphlet they handed out offered information about the union effort and implored Hannam Chain Chief Executive Kee Whan Ha to meet with organizers.

Ha was there to give the keynote speech for the World Korean Business Conference, historically known as the hansang.

Conference organizers blocked all but a few corners of a few signs from the publicity photos by using raised cloths and suit jackets. But workers were still able to protest and hand out fliers all three days of the conference, called the “largest gathering of Korean businesses” in the world, with participants from 60 different countries.

The moment served as a highly appropriate visual for the state of labor in Los Angeles, where hotel workers are on strike, janitors are marching to demand employer accountability and even Hollywood writers are picketing. Those at the top celebrate their successes, while their unhappy workers are ushered out of the frame for appearances’ sake.

This was the first time the hansang had taken place outside of Korea since it began in 2002. The conference connects Korean companies to firms in overseas markets, and it now bills itself as the largest Korean business convention in the world, with participants from 60 different countries.

Koreatown sees unionization battles at Coway, a South Korean air conditioning manufacturer; the grocery store chain Hannam Market and the Korean barbecue chain Genwa

“This is a recognition of the importance of Korean American customers and firms to South Korean companies, and vice versa,” said Edward Taehan Chang, a professor at UC Riverside who has attended the hansang multiple times.

The Oct. 11 protest focused on Hannam Chain, but many companies attending the conference also face union battles in South Korea. More than 14% of South Korean workers are unionized, while just over 10% of U.S. workers are, the lowest rate on record, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Coway’s South Korean workers recently unionized, and Coway executives recently recognized their union, but the company has declined to meet with Coway’s U.S. workers.

It’s unsurprising that similar labor issues prevail in both countries. South Korean capitalism resembles no country’s so much as the United States’. It’s one of the reasons the 2019 film “Parasite’s” critique landed with Oscar voters in America, who anointed it the first foreign film to win best picture.

The film’s director, Bong Joon Ho, held a lively press tour in the U.S. and gave a quote I often return to: “We all live in a country called capitalism.”

Ho’s quote always makes me think of Koreatown, where people from wildly diverse backgrounds are united for the purpose of work. At least 59,437 workers live there, according to the census. Ten percent of the neighborhood’s businesses are restaurants, and 15% of the neighborhood’s residents work in restaurants, according to a new UCLA study in partnership with the Koreatown Immigrant Worker’s Alliance.

I think it’s fair to call it the true downtown of Los Angeles — the densest neighborhood west of Manhattan, walkable, diverse, always open. It’s also one of the last places that wage workers can find a room to rent within their price range.

These factors have allowed many immigrant families to make a life, but they also create the conditions ripe for labor exploitation. There are an estimated 9,700 restaurant workers in Koreatown, working at 704 restaurants in two square miles, according to the study. And 72% of restaurant workers in Koreatown earn less than two-thirds of the median hourly wage for the county, the study reported.

More than half of Koreatown’s restaurants are small businesses with fewer than 10 employees. Small businesses are struggling to meet rent all over Los Angeles in the wake of the pandemic’s disruptions, and when they seek to cut costs, it’s often the wage workers they employ who bear the brunt. A lot of immigrant labor exploitation actually occurs at the hands of other immigrants, and many of those accused of labor exploitation once worked the same jobs.

Korean Americans account for about a third of the population of Koreatown, but they own the vast majority of businesses in Koreatown and properties as well, according to the study.

I think these ownership patterns are in part a response to historical trauma. Many Korean Americans came after the Korean War and sacrificed family ties, country and identity for the chance to start their own businesses and gain some control over their economic destiny.

Genwa, where a plate of galbi costs around $75, is reportedly the first Korean barbecue restaurant in the country to unionize.

And after the devastation of the Los Angeles riots in the neighborhood, owning land was a way of preventing future losses. Tragedy has only deepened entrepreneurship’s importance in the Korean American community.

Ha represents that ideal for many in the Korean community. Hankook Property Management Co., which he owns, oversees at least 600 apartment units and 150,000 square feet of retail space, much of it in Koreatown. His grocery store, Hannam Chain, was the neighborhod’s first Korean grocery store. He’s been a fierce advocate for Koreatown business owners, and the city named a local intersection after him in 2013.

He is perhaps best known for his radio interviews during the 1992 L.A. riots, exhorting business owners to arm themselves and “Protect your business. Don’t go home. Your business is your life.”

Here’s what I would add to that. A business affects not just the owner’s life, but all the people who work for it, and all the other companies it works with, and the workers they employ too.

Your business may be your life, but just as importantly, it’s your employees’ lives too. A union would be a simple and powerful way to recognize that.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.