Detective alleges sexual hazing on LAPD’s Centurions football team

- Share via

He was a former Pac-10 football player, one of the best recruits on the LAPD’s amateur team, the Centurions. He joined because a supervisor told him it was a quick route to promotion and good assignments.

But as he walked off the field at his first all-weekend practice, that veteran supervisor and others on the team began to yell: “Rookies to the locker room.”

What followed, according to court documents, was an alleged hazing, a group sexual assault that the young linebacker said he didn’t dare report: Who would he tell, anyway? The alleged assailants were Los Angeles police officers, the people meant to investigate such crimes. And their victim? He was a rookie cop.

That rookie officer is now a respected detective. He reported the alleged assault to the L.A. Police Commission’s inspector general in March. And on Monday he filed a legal claim, a precursor to a lawsuit against the city that sets out his allegations. The Times is not naming the officer as a possible victim of a sexual assault, which allegedly occurred on Feb. 7, 2009.

The officer says he told his parents and three friends in the years after the alleged assault. He did not speak to The Times for this story, although two friends and his attorney did address the allegations.

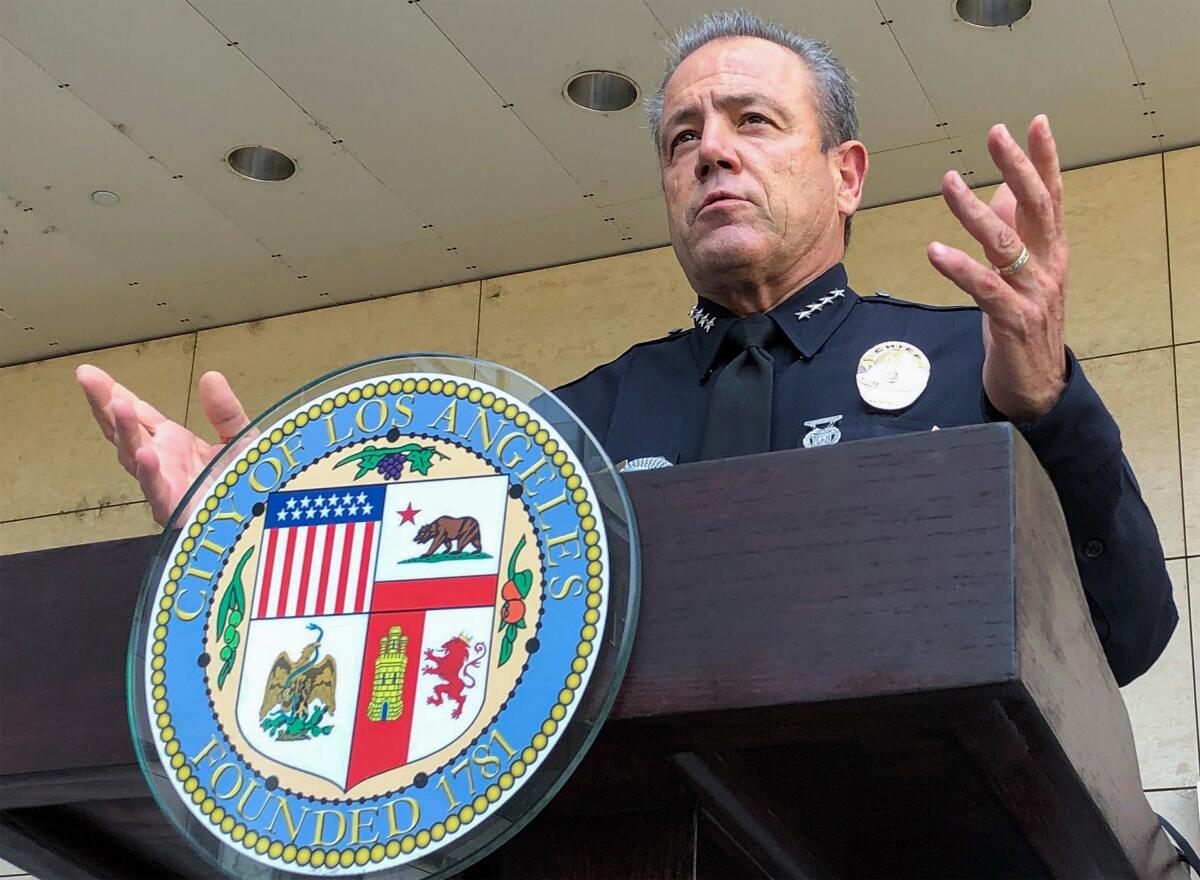

After The Times reported on the legal claim Wednesday, LAPD Chief Michel Moore said that the department had launched an investigation earlier this year. “Should the investigation reveal any truth to these allegations, those responsible will be held accountable,” he said. Messages left on a phone number and email address listed on the Centurions website were not returned.

Part of the LAPD’s athletics program, the football team has more than 50 players on its roster and plays a six-game schedule, generally against teams from other local law enforcement agencies. After a two-year hiatus because of the pandemic, the Centurions started playing again in 2022.

The team is registered as a nonprofit and is frequently featured on the LAPD’s social media posts and in official news releases. For some officers, the squad is both a networking opportunity and a way to continue playing a sport they grew up with. For the detective who filed the claim, his attorney says, it turned out to be a nightmare.

“He is a tough son of a gun with a strong depth of character and a decorated career despite really being put through it by this evil,” said Michael Morrison, a veteran sex abuse lawyer who was part of nearly $1 billion in L.A. settlements in priest abuse cases.

Morrison said his client is haunted daily, and that “he had guilt and shame and humiliation.” According to the legal claim, after the assault the rookie officer felt “like he was in a gang that he could not leave without putting himself in danger.”

A string of recent controversies have put to a test LAPD Chief Michel Moore’s quest to get his department into shape before stepping down in the next year or two.

Within minutes after practice ended, the document states, he was pressured to strip naked and face a gantlet of more than 30 men hurling a barrage of abuse.

They hollered for him to show his penis. They grabbed at him and threw unidentified liquids his way. Before the attack ended, the filing alleges, a Centurion teammate rammed a hard object into his anus.

That hazing allegedly included one officer who is now a captain, a few lieutenants, several sergeants and former Officer James C. Nichols, who is serving a 25-year prison sentence for raping and sexually assaulting women while on duty, according to records.

“You one of us now,” one officer told him after pulling him to another area following the hazing, seeing his visible distress, according to the legal claim.

Court records say the intervening officer mentioned Ricardo Lizarraga, a former Centurion who was gunned down in the line of duty in 2004 — and whose suspected killer was found hanging in his cell in the county’s Twin Towers jail. “Lizarraga was one of us,” the officer said, according to the filing. “We took care of him; we take care of you.”

Fearing retribution, the rookie officer said nothing at the time, according to the legal claim.

But he did tell some of those closest to him, one person around the time of the assault and another in recent years, those individuals confirmed to The Times.

For decades, Cleveland’s Core humanities program fostered a culture of sexual abuse in which teens were exploited by their teachers, former students say.

Morrison said the now-detective, shortly before deciding to file his legal claim, ran into one of the alleged perpetrators. That officer, the lawyer said, claimed he was a different person now and expressed amazement that the detective did not “rat them out” despite the culture of silence. Morrison said that conversation triggered his client’s need for justice.

As he walked off the field that day 14 years ago, according to the legal claim, the rookie heard two team veterans mutter that they didn’t like when the team did “this” as they walked away in their pads to their cars. The other players then herded the rookies into a dimly lit training room and called out their names one by one.

From the other side of the door in the locker room at Bishop Mora Salesian High School where they practiced, there were audible screams from those who had already been summoned, according to the legal claim.

The officer who is now pursuing litigation said he was last to go among the rookie players. He alleges that he was ordered to strip naked while surrounded by more than 30 screaming men. At first, the legal claim stated, he kept his underwear on despite the barrage of homophobic abuse, shouts like, “Show us your d—, f—!”

He slipped off his underwear and covered his genitals, according to the claim. The men screamed to see his “little c—” as he walked the gantlet, the claim alleges, and others grabbed his arms, threw liquids and jabbed at his backside with a hard object.

At the showers, he alleges he was required to climb into a trash bin filled with ice water as the officers yelled abuse about his body. As he climbed out, he saw colleagues making fists, and he took up a defensive posture with his knees bent. According to the claim, that is when he felt what he says was a bottle penetrate his anus.

The statute of limitations for criminal charges has expired. The civil claim, which says the detective suffers from post-traumatic stress syndrome, asserts charges of assault, negligence and emotional distress.

Former LAPD Assistant Chief Al Labrada said he wanted to ‘set the record straight’ after he was accused of stalking by a fellow officer.

Friends of the detective agreed to share their recollections of conversations with him on the condition that their names not be used for fear of retribution.

“He seemed really embarrassed, I almost want to say ashamed, because he had always been an athletic, kind of an alpha-male type of character,” said one close childhood friend, adding that it was “almost as if he was afraid for his own safety and was scared because he didn’t know what to do.”

A second friend told The Times that the detective confided in him about a week after the alleged incident. They would speak by phone nearly every day, according to the friend, which caused him to be concerned when the detective became withdrawn and distant. In conversations over the ensuing years, the friend said, the detective conveyed his dread of being found out and going to work while keeping such a painful secret.

Among those the legal claim identifies as being part of the gantlet — in addition to Nichols — is Dana Smith. An officer in Central Division, Smith was sent to a board of rights hearing in July and is facing potential termination, according to a claim he filed against the city seeking to overturn discipline for an excessive force complaint. Smith appealed a disciplinary panel recommendation that he be suspended for an incident in which he struck a suspect in the face twice and was discourteous.

According to the detective’s legal claim, Capt. Anthony Espinoza was also among those present in the locker room that day in 2009. He now runs the LAPD’s innovative management unit.

Lt. Matthew Ensley of the Pacific Division is another officer listed in the litigation. Raymond Puettmann, also allegedly present for the locker room abuse, has since risen to lieutenant in the training division.

Emails sent to the four officers at their LAPD addresses went unreturned. The legal claim does not specify their roles in the alleged assault.

In a recent court filing, former LAPD Cmdr. Nicole Mehringer contested her firing, arguing the department has overlooked — or even helped cover up — similar behavior by dozens of male supervisors.

The Times spoke with several officers who played on the Centurions over the years. One former officer, who requested anonymity to speak freely about the team’s culture, said that before joining, he heard stories of hazing. In at least one instance, he said he heard that new recruits were forced by senior team members to strip off their clothes and jump into an ice bath.

The officer said such frat-like pranks were far more common in the 1990s, but the team’s culture was largely cleaned up during the tenure of former Chief Bernard Parks, who took a particular interest in the team.

In the early days, the team played its games in the L.A. Coliseum. It won several titles as part of the National Public Safety Football League, playing against teams from Las Vegas, Houston and Chicago. The Centurions’ main rival was the New York Police Department, with regular matchups billed as the Super Police Bowl.

Being a part of the team comes with its perks, former players said. Officers can receive days off to practice or travel, and plum assignments in specialized units. It also carries risks. Players are on the hook for their own travel expenses, and many get private insurance to cover medical expenses in case they get injured while playing.

Historically, the team has had its own cheerleading squad, a mix of sworn and civilian employees. When they weren’t cheering, members performed other tasks, such as organizing picnics, barbecues and other events to raise funds for the team’s main charity, the Blind Children’s Center.

Centurion members have also been known to get into brawls when playing out of town, one former officer who played on the team said, adding that department leaders have turned a blind eye to some of the heavy drinking that went on in years past.

In the wake of the alleged 2009 assault, the detective said he feared those involved could get him fired, or even “find a way to kill him,” if he said anything.

His escape came in the form of an injury, which prevented him from finishing the 2009 season, according to the claim. He never returned to the team.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.