Lack of fentanyl knowledge deters families from talking about it. Here’s how to start the conversation

- Share via

Despite an increase in fentanyl-related deaths and surging police seizures of the drug, a new survey finds that parents are not talking about the dangers of fentanyl with their family because they don’t feel knowledgeable enough on the topic.

Earlier this year California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta deemed the growing popularity of fentanyl a “multifaceted public health and safety issue.” His statement followed the seizure of a combined 40 pounds of fentanyl in two separate cases in Merced County.

Song for Charlie, a nonprofit that raises awareness of counterfeit pills laced with fentanyl, in partnership with the California Department of Health Care Services, commissioned a survey of 1,574 California residents, which included parents, young adults and teens, in May and June of this year.

Four in 10 young adults and half of teens surveyed said they aren’t knowledgeable about the issues surrounding fentanyl.

Fentanyl deaths among teens more than doubled from 2019 to 2020, increasing from 253 to 680. Last year, the number jumped to 884, according to a report from the Journal of the American Medical Assn.

Parents reported “lack of knowledge” as a key barrier that keeps them from talking about the issue with their children.

Young adults cited “fear of judgment, lack of comfort and potential consequences” as some of the most significant obstacles to discussing prescription pill misuse with their parents.

To encourage conversations between youth and their guardians, the two entities established the online tool the New Drug Talk: Connect to Protect. The goal is to give parents confidence so they can speak to the issue in an informed way, said Ed Ternan, president of the nonprofit.

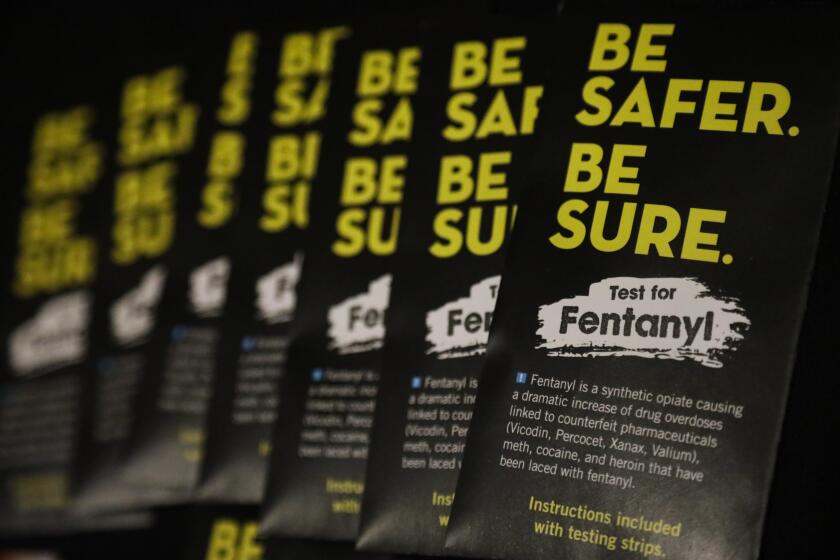

Fentanyl is often mixed with other drugs (including heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine) to increase potency, but it can be deadly. Test kits can help.

Here are tips and guidance that Song for Charlie and its partners have shared to fuel ongoing conversations at home.

What to know before you talk

As parents plan for the discussion, the first step is to be educated on the subject. The online tools are a good way to become informed.

Parents aren’t expected to become experts on the topic, but it’s recommend they choose three concepts to cover, such as why fentanyl is risky, how fentanyl can be mixed with counterfeit pills and what can be done.

The learning material provided in the online tools is offered in three grade levels — middle school, high school and post high school — as well as information for young people who aren’t in school. The material is also categorized by a person’s knowledge of fentanyl.

How to start the conversation

As parents are getting familiar with the facts, the nonprofit recommends letting teens or young adults know that they want to talk about fentanyl.

“The dialogue should come out of a place of love and concern, no judgment, and really give the young people the space to respond,” he said.

Ternan reminds parents that this conversation isn’t a lecture, it’s a dialogue. Parents shouldn’t expect to discuss this topic in one sitting. “You can take breaks or come back to the conversation at a later time,” he said.

When parents feel prepared, they should open the discussion by asking questions or offering to learn about this topic together. Ternan recommends saying: “Hey, I’ve heard something that has me concerned, have you heard about this too?”

“What are you hearing?”

“Maybe we should both learn about this new issue together?”

Don’t be afraid to practice the talking points with your partner, a friend or in front of the mirror, he said.

Be prepared for your child’s response

Parents and guardians should be mindful of how a child can react to this conversation.

The child might say things like, “I know what I’m doing, don’t worry about me,” or “Don’t you trust me?” Try to anticipate how the conversation may go and come prepared to respond calmly.

Even if the child feels the information doesn’t pertain to them or their lives, Ternan said, parents can appeal to their child’s care for their friends, who could become victims of the drug.

Ask about your children’s friends

During a child’s teen and young adulthood years their friend group is very important to them, Ternan said. Parents can ask what their child’s friend group is saying about the drug as another way to navigate the subject.

Fentanyl is more dangerous than most other drugs

According to Ternan, the way parents approach the conversation about fentanyl will be different from the way they learned about the dangers of drugs in the past. Fentanyl is more potent and dangerous than most other drugs, he said.

“We were warned about getting off the wrong track and our interaction with drugs was going to be like a [path]; if you did too much you would become dependent and have negative consequences down the line,” he said.

Now, parents, advocates and educators need to intervene sooner.

“It’s less like a path and more like a minefield where kids, their first, second or third step into that minefield could be fatal,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.