Do students have privacy rights when it comes to their parents? It’s complicated

- Share via

As a wave of California public school districts explore policies around students and gender identity, the extent to which state law grants young people privacy rights from their parents has come under a sharp spotlight. And while the state’s Democratic leaders contend such privacy rights are clear-cut, constitutional experts say the legal realities are more nuanced, igniting a heated debate likely to move its way through the courts.

The question of what responsibility schools have for alerting parents if students say or do something to identify as gender-nonconforming is popping up on school board agendas in conservative pockets across California. In many cases, the policies are being pushed by a newly elected class of emphatically conservative trustees, ushered in last year as part of a broader revolt in “red” California against COVID-related mask mandates and school closures.

The Chino Valley Unified School District in San Bernardino County in July became the first to adopt a policy requiring schools to inform parents if a student identified as transgender or gender-nonconforming, followed soon after by Murrieta Valley Unified and Temecula Valley Unified in Riverside County. The policy is under discussion in other districts, including Orange Unified.

Under Chino Valley’s policy, district staff are required to notify parents in writing within three days if they become aware of a student using names, pronouns or changing facilities such as bathrooms that do not match their biological sex. The language mirrors that of a failed bill proposed earlier this year by Assemblymember Bill Essayli (R-Corona).

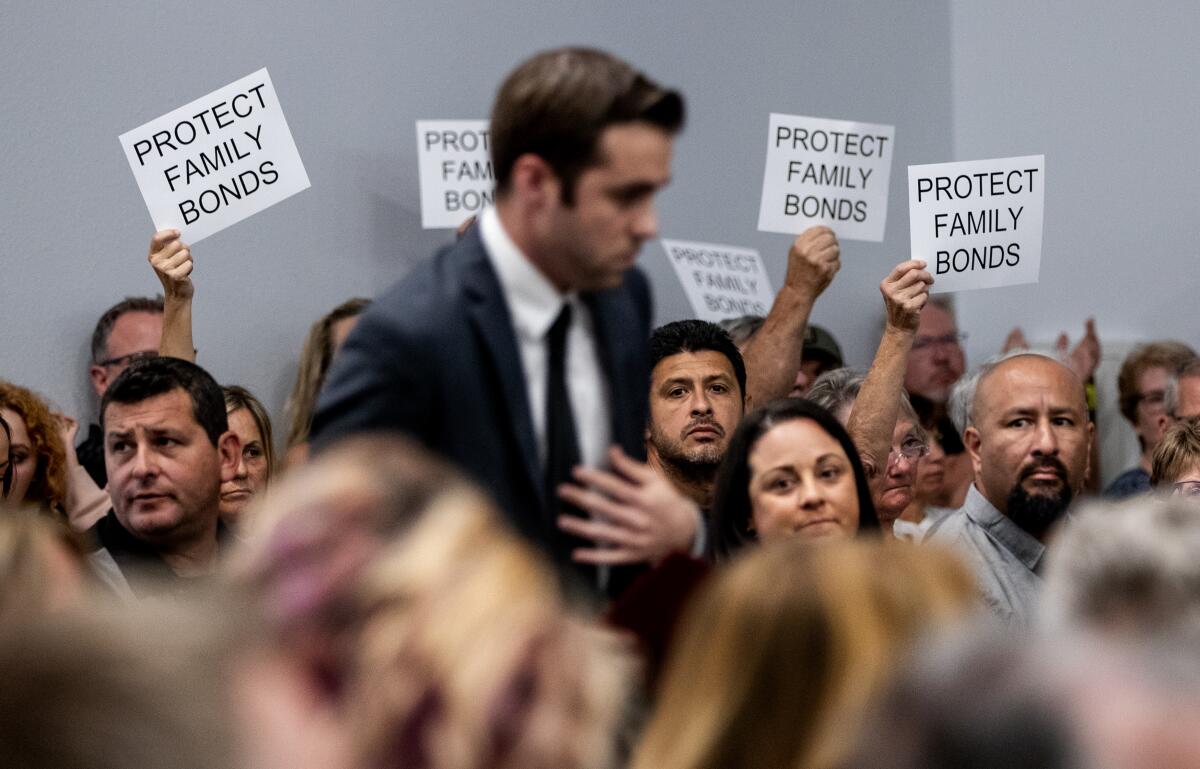

School board hearings on the issue have proven divisive, featuring impassioned debate and similar talking points.

Supporters of a parental notification policy argue parents have a fundamental right to be involved in all aspects of their children’s lives, particularly when it comes to issues such as sex and gender. Opponents — including state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond and California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta, both Democrats — contend such policies violate student privacy rights ingrained in state law and the education code. “Outing” transgender students to parents and the school community, they maintain, can put a child at serious risk.

On Monday, Bonta sued the Chino Valley district, calling for an end to its parental notification policy on the grounds it violates civil rights and privacy laws. He has previously noted such policies flout legal guidance issued by the California Department of Education, which expressly states schools may not disclose a student’s gender identity without the student’s permission.

The parental notification policy puts transgender and gender-nonconforming students in “danger of imminent, irreparable harm” by potentially “outing” them at home before they’re ready, according to the lawsuit, which asks the San Bernardino County Superior Court to ban the practice.

Legal scholars say the issue is more nuanced than the political rhetoric may indicate.

“The law on this is unclear, because it is a new issue,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law. “The students being minors does make the legal questions more difficult, but even as minors they have privacy rights.”

John Rogers, a professor at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, described the debate as a “super-complicated issue.”

The California Education Code, Rogers said, is made up of policies that help frame and guide the state’s system of public education. But it does not “lay out what to do in this particular instance, where we’re talking about student’s gender identity,” he said. At the same time, he noted, the code does prohibit discrimination on the basis of disability, gender, gender identity, gender expression, nationality, race or ethnicity and religion.

“There certainly is an acknowledgment that parents have had a certain degree of rights to information relative to minor children,” he said. “But those rights are not absolute, and that minor child also has certain rights that relate to their privacy, their autonomy, and not being discriminated against.”

Rogers was among several experts who said the balance between parental rights and student privacy rights likely will be sorted out in the courts.

Escalating school board culture wars, the lawsuit alleges transgender students’ rights are violated by parent notification policies.

Two federal regulations also come into play: the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment. These measures affirm parents can access student records and federally funded instructional material until a child turns 18. They also allow parents to opt their children out of questionnaires on topics such as political affiliation and religious practices. But there are limits. For example, school staff cannot include information in a student’s official record that is based solely on observation or informal conversation between students and teachers.

Essayli, an attorney and former federal prosecutor, is among the conservatives challenging Bonta’s legal arguments. In early August, after Bonta announced he would open a civil rights investigation into Chino Valley’s new policy, Essayli issued a public letter demanding Bonta specify what laws were being violated.

“The Supreme Court precedent on this is really clear that parents have a civil right, a constitutional right, to raise their kids, even if the state doesn’t agree with the manner in which they do it,” he said in an interview.

Essayli said the legal guidance for schools from the Department of Education that Bonta has cited is tied to Assembly Bill 1266, which provides certain protections for transgender students. The bill, signed into law in 2013, maintains transgender students are allowed to play sports and use bathrooms consistent with their gender identity.

Essayli argues the bill language does not specifically address disclosures to parents. “There is no right to privacy for kids from their parents,” he said. “It does not exist. They certainly have it from third parties. You can’t disclose the kid’s medical condition to third parties, but we’re talking about their parents.”

Sarah Perry is a senior legal fellow with the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at the Heritage Foundation, a right-wing think-tank. Perry also questioned the basis for some of Bonta’s legal assertions, and said case law on student privacy rights is conflicted. She predicted the issue “is very likely to maneuver its way up to the Supreme Court, precisely because we’re seeing federal courts reach different outcomes as to whether or not it’s the parents who have an interest in knowing, or whether or not the child’s interest in privacy is superior.”

Backers of the policy say parents are best suited to deal with kids experiencing gender dysphoria. Foes say school might be some students’ only haven.

In support of his legal argument, Bonta has cited C.N. vs. Wolf, a 2006 case involving a 17-year-old female high school student who was suspended after repeatedly engaging in public displays of affection with another girl in a manner the principal deemed a violation of campus regulations that set limits on physical intimacy.

The student sued, alleging in part that the principal violated her privacy rights under California law by disclosing to her mother she had been kissing another girl. A federal district court noted in its ruling that California law does afford students the right to privacy in matters of sexual orientation. But it also found, in this instance, the principal had a conflicting duty under the state education code to notify parents of the reasons a student is being disciplined.

Similar cases have popped up across the U.S. In July, a federal court dismissed a case brought against the Chico Unified School District by a parent who alleged the district had violated her constitutional rights by failing to tell her that her child had asked to use a different gender pronoun. The lawsuit alleged the district’s policy granting students a right to privacy amounted to “socially transitioning” students without parental consent.

U.S. District Court Judge John Mendez said in his ruling: “The issue before this court is not whether it is a good idea for school districts to notify parents of a minor’s gender identity and receive consent before using alternative names and pronouns, but whether the United States Constitution mandates such parental authority. This Court holds that it does not.”

The Center for American Liberty, the conservative group pressing the case, has appealed the decision to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

As the parental notification policies gain momentum — and the legal machinations move forward — staff in affected districts have expressed concern about how they’re supposed to carry out the new policies.

Greg Goodlander, president of the Orange Unified Education Assn., said teachers haven’t received any training on the parental notification policy the school board there is considering, and that any such proposal should be bargained as part of the union’s contract.

“In addition to the legal issues, this policy requires certificated employees to have the appropriate knowledge, training and time to have communication with students and guardians about sensitive and confidential issues,” Goodlander wrote in a letter to the board. “With the number of requirements and expectations already placed on certificated staff, this is an unreasonable and highly concerning expectation.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.