California voters will decide on measure allowing cities to expand rent control in 2024

- Share via

Will the third time be the charm?

After trying and failing twice before, a coalition of housing advocates led by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation have collected enough signatures to place a measure on the 2024 ballot asking voters to repeal a major restriction on rent control, in effect allowing more cities and counties across the state to cap rents on more types of homes.

California Secretary of State Shirley Weber’s office announced Wednesday that the initiative has qualified for the November 2024 ballot after its proponents submitted more than 800,000 signatures and enough were certified as valid.

In a news conference Thursday, backers of the Justice for Renters Initiative said the changes would give Californians living on the edge an ability to hold on to their housing as wages lag behind increases in rent across the state. Supporters said that many people are one rent increase away from homelessness and that the initiative would give cities and counties more tools to prevent tenants from being displaced.

“Many of our members are the working poor,” said Ada Briceno, co-president of Unite Here Local 11, who noted that her union members are on the picket lines right now for the same reasons that the ballot initiative is necessary.

“They live paycheck to paycheck. They’re couch surfing. They’re living in their cars and struggling to pay rent,” she said. “Many of them have been pushed out of their communities and now have long hours of commute.”

Some of the initiative’s supporters include the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles and the California Nurses Assn., along with Housing Is a Human Right, the housing advocacy division of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation.

If the initiative succeeds, it would repeal the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, a state law that prohibits rent control from being placed by cities and counties on single-family homes and apartments built after 1995, among other prohibitions. The measure would also specify that the “state may not limit the right of cities and counties to maintain, enact, or expand rent control. However, the state still could set some minimum protections for renters, like the current statewide limit on rent increases,” according to a summary from the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Cities including Los Angeles and San Francisco, among others, already have limits in place for whether rent can be raised on a yearly basis, if at all. The state has also passed regulations in recent years that limit rent hikes to either 5% plus yearly inflation or 10%, whichever is lower.

In recent years, smaller municipalities have also begun instituting their own rent control ordinances.

In 2018 and 2020, the same groups backed efforts to pass similar ballot measures. In both instances, nearly all of the funding for the initiative came from the Los Angeles nonprofit AIDS Healthcare Foundation, which put about $60 million into the losing efforts. Both efforts to repeal the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act lost by nearly 20 percentage points in 2018 and 2020 after $100-million-plus campaigns in which landlord groups outspent supporters of the initiative by more than 2 to 1.

One of the biggest opponents of the last two efforts was the California Apartment Assn., which is gearing up to oppose this latest proposition as well.

If this measure passes, “landlords lose any hope of ever charging fair market value for their investment,” Tom Bannon, the association’s chief executive, said this year when supporters began collecting signatures. “There is little incentive to keep the unit on the market, let alone invest in improvements.”

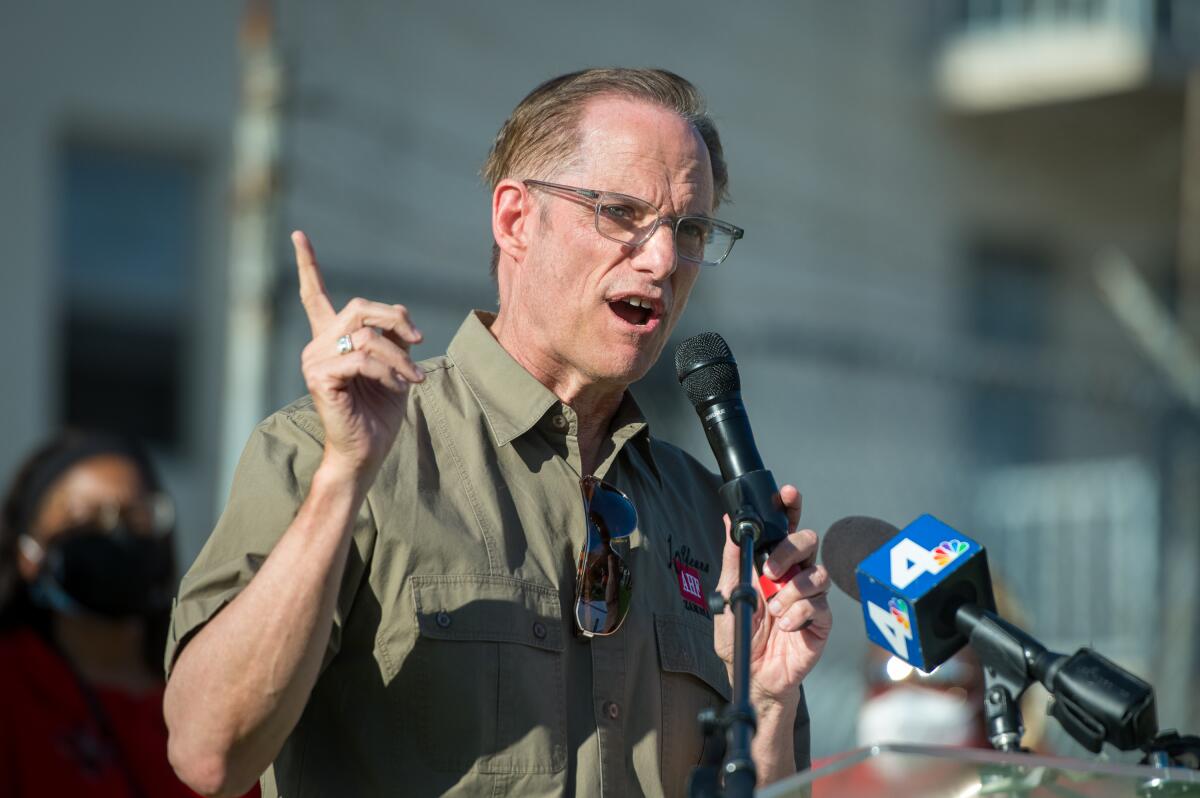

Michael Weinstein, president of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, and others said this time will be different because the situation is so much more dire.

“Renter protection legislation goes to Sacramento to die, and we have no hope of getting it through the Legislature,” he said. “The main reason why we have a better chance now is that the situation has gotten so extreme. Rates of homelessness are going up. Where are people going to live? The population of California is shrinking, and the California dream is dying.”

Around the time of the first ballot initiative, the foundation — best known as a behemoth in the healthcare industry, with more than $2 billion in annual revenue earned largely from its chain of pharmacies and clinics — began purchasing single-room-occupancy hotels and other apartment complexes in Skid Row and other parts of Los Angeles. Its goal has been to provide homes to low-income residents more quickly, cheaply and humanely than private developers, public agencies and other nonprofits.

Some of these buildings, The Times found, have been plagued by problems, including substandard conditions and faulty elevators, which led several residents to sue. The foundation settled a lawsuit about an elevator at one building for more than $800,000, but other class-action lawsuits alleging overall uninhabitable conditions at two buildings remain pending.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.