Eagle Rock’s ‘Pillarhenge’ will finally disappear. In its place, a giant boat?

- Share via

If P-22, the late mountain lion, was the unofficial mascot of L.A., then Pinky the papier-mâché bird was the decidedly less majestic mascot of Eagle Rock, the small, hilly neighborhood tucked on the city’s northeast boundary.

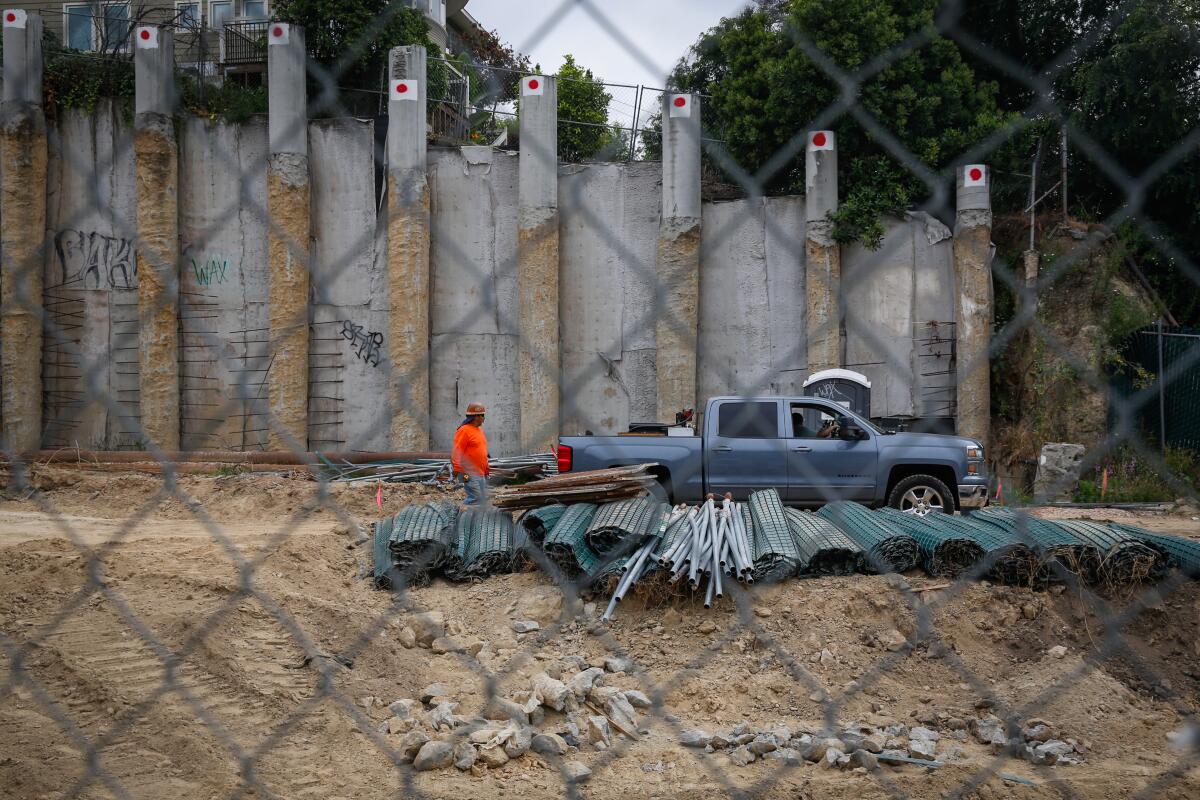

No one’s quite sure how Pinky popped up. Around 2014, the bird appeared in a nest atop “Pillarhenge,” a famous (or infamous) series of columns built as the foundation of a would-be Great Recession-era housing development on Colorado Boulevard.

The development was never finished. Abandoned since the 2008 housing crisis, the property has served at times as a homeless encampment, dumping ground and playground for graffiti artists.

The pillars became a white elephant of the recession, an eyesore that locals have come to love, hate or begrudgingly accept. While Stonehenge evokes mysticism and Wiccans, Pillarhenge evokes confusion and dysfunction, serving as a concrete reminder of L.A.’s inability to deal with its housing woes.

The bird had a deeper fan base, becoming an Eagle Rock celebrity with a line of T-shirts and tapestries. For the last eight years, Pinky watched over a city that couldn’t quite figure out how to house itself.

Then in April, Pinky was gone, stripped from its pillar-top nest. A sign perhaps? Was Pillarhenge coming down too?

Residents wondered what would rise in its place on 1332 Colorado Blvd., a long, narrow property that has never been developed.

Before the pillars, the property was known among locals as the place where an LAPD officer shot 18-year-old Mark Moser to death in 1978 after Moser’s pickup truck collided with an undercover police car at the end of a stakeout and subsequent car chase.

Resident Kevin Grace, Moser’s classmate at Eagle Rock High School, said the property has carried a bizarre mystique since the killing.

In March 2015, Grace co-founded “Friends of Pillarhenge Park,” a Facebook group tracking the property’s development and advocating for its potential use as a park. To date, the group has 824 members.

Developers have attempted to build something on the property over the last two decades, but never a park. Jay Vanos of Vanos Architects has been involved with the site since 2003, when he worked with a developer envisioning a 17-unit live-work space there.

It didn’t come to fruition and sold to another developer, who erected the now-famous pillars before going bankrupt. The lender took control for a few years before the property was sold to Imad Boukai for $1.9 million in 2016.

Boukai, chairman of Anaheim-based company General Procurement Inc., envisioned a four-story mixed-use development with 31 apartments above two levels of parking and commercial space.

He tapped Vanos, who planned a structure that would take up the vast majority of the relatively small lot, which covers just over half an acre. The plans became public in 2017, and due to its ship-like look, residents started calling it the Love Boat, a nod to the 1970s sitcom set on a cruise.

“Let their imaginations take them where they will,” Vanos said.

As with most small towns subsumed by a big city, Eagle Rock residents felt protective of the community and wary of potential developers. They voiced strong opinions. Months of discourse and meetings with council members ensued, with some locals jeering at the nautical design and others expressing relief that the site would finally be developed.

“I’d rather suck it up and see it developed into a functional property,” said Grace, who was born in Eagle Rock. “Right now, it looks like something from a forgotten town. That’s worst-case scenario.”

The Eagle Rock Assn., a volunteer group founded in the 1980s aiming to guide the community’s growth in a sustainable way, published a letter in 2017 pointing out the significance of the site’s location. The property parallels a freeway offramp leading into Eagle Rock, so the Love Boat would be the first thing people see when entering the neighborhood.

The letter said the board was split on the design, but members support the development because the property had been “blighted and abandoned for so many years.”

Progress stalled again, and Boukai sold the unfinished property in 2022. He declined a request for comment. A source familiar with the deal suggested that building costs became too expensive since the lot is on a steep hill that requires significant grading and maintenance.

Next up was Ara Tchaghlassian, founder of American Tire Depot, a Vernon-based retailer with more than 100 locations. Tchaghlassian sold the tire company in 2021 and bought the Pillarhenge lot from Boukai months later for $2.765 million, real estate records show.

It appears the Love Boat will set sail after all, as Tchaghlassian is picking up where Boukai left off. He declined a request for comment, but a construction permit posted at the site shows the same plans mapped out by Boukai: a four-story development with 31 apartments, including three extremely low-income units, above two levels of parking and commercial space.

Grading began late last year, and Pinky was removed in the spring. The source said the complex will probably be completed in roughly two years.

“I’m sick of looking at it,” said Diane Lopez, who walks past Pillarhenge on her daily stroll. “Just build something. Anything.”

The pillars will remain, though they won’t be visible once the structure is completed, Vanos said.

As for why a developer would take on the headache of Pillarhenge, the answer is simple: the Transit-Oriented Communities Incentive Program.

L.A. has a housing shortage, and it needs a multifaceted approach to address it. As part of its housing element plan, the city is required to zone for a quarter-million homes by 2024.

To reach that goal, the city has introduced various incentives to encourage multifamily development as part of its Housing Element Rezoning Program, and the Transit-Oriented Communities incentive has been one its most successful tools.

The program encourages the development of affordable housing near bus and train stations by offering developers more density and less parking requirements for their projects if they build near transit centers.

According to the city’s planning department, over the last six years, 36% of new multifamily developments have taken advantage of the incentives, and the Pillarhenge project is one of them. It qualifies for the second tier of incentives, meaning it gets a 60% increase in the maximum number of units, an increase in floor-area ratio and a reduction in the number of required parking spaces.

“We need responsible, robust development that’s affordable and successful for Angelenos. Right now, we don’t have enough,” said Greg Good, a senior advisor on policy and external affairs for the Los Angeles Housing Department. “The Housing Department and the rest of the city are working relentlessly to facilitate and expedite that process, and we do that by creating programs that work.”

There are myriad reasons why developers abandon a project: running out of money, permitting problems, pandemics. During a housing crisis, it’s the city’s job to make multifamily housing a viable option for developers.

For Pillarhenge’s latest developer, the incentives may be enough to bring housing to the long-abandoned lot. For now, residents wait to see whether a Love Boat will be better than a Pillarhenge.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.