State orders L.A. County to move nearly 300 youths out of ‘unsuitable’ juvenile halls

- Share via

State regulators on Tuesday gave Los Angeles County two months to move roughly 300 youths out of its two troubled juvenile halls, taking the unprecedented step after finding the county had done little in the last month to come into compliance with a long list of state regulations.

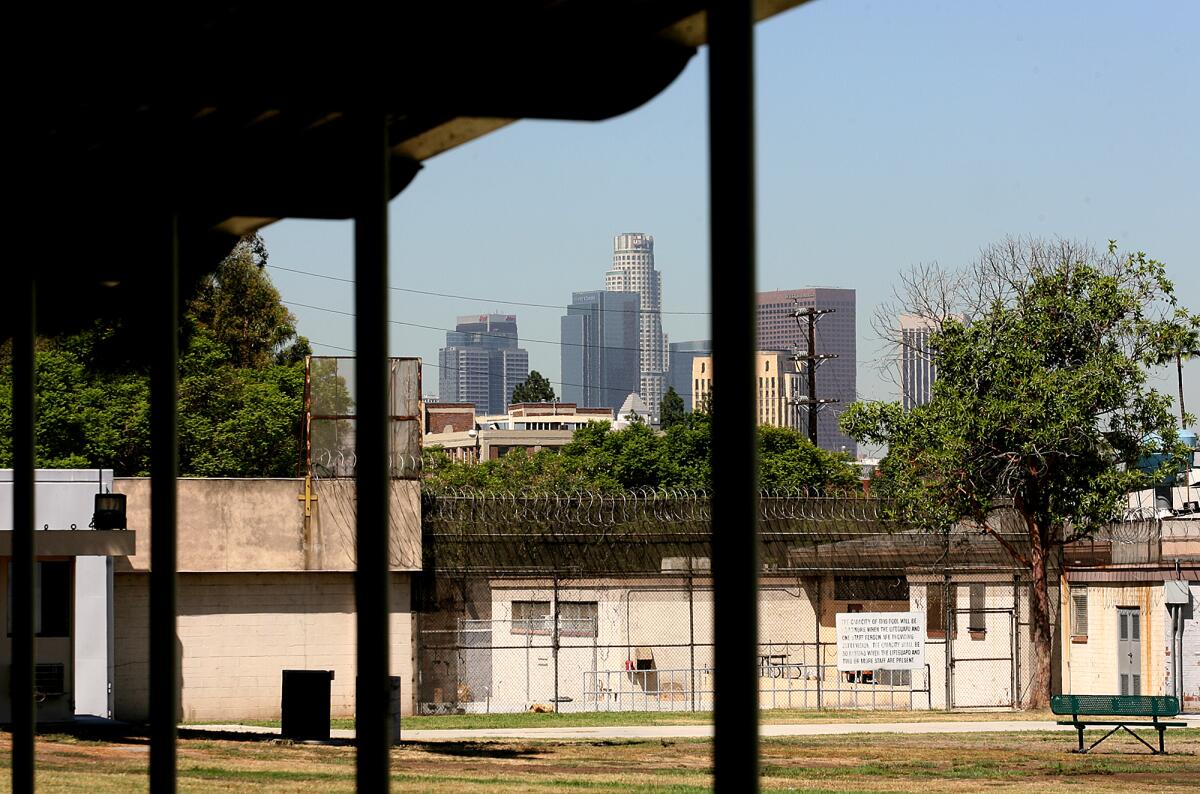

The unanimous decision by the Board of State and Community Corrections leaves the county scrambling to vacate Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in Sylmar and Central Juvenile Hall in Boyle Heights by mid-July. The Probation Department said it plans to move the entire population into Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall in Downey, which was closed in 2019 amid a reduced population and allegations of abuse by staff.

In voting to declare the halls “unsuitable” — meaning they can no longer be used to confine young people — the state board put an end to a years-long back-and-forth with local officials over improvements that were repeatedly promised but never carried out.

The board first deemed the halls unsuitable in 2021, a step it had never taken before but gave probation officials repeated opportunities to come back into compliance with minimum requirements. The board put off a decision to close the halls in April, drawing the ire of youth advocates who said the department had been given far too many second, third and fourth chances.

The board decided Tuesday it was done giving extensions.

“The time has come to take an extraordinarily difficult move,” board Chair Linda Penner said.

State regulators have highlighted numerous problems within the two facilities.

An 18-year-old was found dead of an overdose Tuesday in an L.A. County juvenile hall, just weeks after a county report raised alarms about the facility. Hours later, a state agency issued a report recommending that the county’s juvenile halls be closed.

An acute staffing crisis has meant not enough officers working to let youths out of their rooms, much less outside into fresh air. Those same limitations have led to cancellation of family visits, limited or nonexistent schooling or even stalled access to therapy — all issues that advocates, staff and juveniles in custody have said lead to additional fights and deteriorating mental health conditions for detainees.

Conditions within the facilities have worsened as violent incidents and overdoses have risen. An 18-year-old was found dead in his room at Nidorf earlier this month of an apparent overdose — the first time a youth has died at a juvenile hall since 2010, according to a county spokesperson.

Regulators will formally notify the county by Wednesday that it will have 60 days to relocate the roughly 280 youths currently in Probation Department custody to Los Padrinos.

A team of consultants working for the county had implored the state regulators to give the county 150 days so it could transfer the population to Los Padrinos with the “least amount of disruption.”

“This condensed timeline will undoubtedly, undoubtedly contribute to some level of chaos and confusion,” said Margarita Perez, a former assistant chief for the Probation Department, who represented the county in the meeting. “It will also create — and again, it goes without saying — a logistical nightmare for the county.”

The Probation Department was accused last year of conducting a rushed transfer of youths from Central to Nidorf in order to avoid criticism during a pending inspection by state board investigators. The chaotic, poorly planned move led to violence, injuries and eventually a rebuke from the L.A. County Office of the Inspector General.

The county consultants struck a deferential tone on Tuesday as they implored regulators to give them more time, while acknowledging Central and Nidorf were unsuitable to house youths. Perez said the department “clearly, clearly, clearly” understood changes were long overdue and acknowledged the county was “asking a lot.”

The board refused, appearing weary of various promises from a rotating cast of Probation Department leaders.

“It is a plan that is way too late,” said board member Kirk Haynes, Fresno County’s chief probation officer.

“Your concerns for the disruption of moving youth are outweighed by our concerns of the disruption they’re living in right now,” said Kelly Vernon, chief probation officer of Tulare County. “Every extension has already been made that possibly can.”

Over the last two years, the state board has repeatedly found the two juvenile hall facilities out of compliance with state regulations. Last month, the county was given yet another chance. After a lengthy meeting where high-up county officials implored the regulators for more time, regulators put off an anticipated vote on a shutdown, citing the county’s good-faith effort to course-correct. Among other promises, the county said it was reassigning 100 field deputy probation officers to the chronically short-staffed halls.

Inspectors say the promise of rapid reform never came to fruition.

In a memo by top staff of the Board of State and Community Corrections, regulators said they were unable to confirm that 100 deputy probation officers had been reassigned. And staff members were still regularly calling out for their shifts, forcing officers already on duty to cover for them and exacerbating the staffing crisis.

Between April 10-28, regulators found 34 staff members who had worked 24-hour shifts at Nidorf. Inspectors found that youths continued to be given little in the way of programming, with many crowded around TVs blaring YouTube. People still reported they sometimes urinated in a receptacle in their rooms because no one came to let them out to use the bathroom.

“There is no measurable progress toward compliance being observed,” regulators wrote.

Interim Chief Probation Officer Guillermo Viera Rosa said after the vote that he was disappointed state regulators didn’t give his department more time but agreed the two halls should no longer be used for the bulk of young people in the county’s custody. In contrast to what his representatives predicted at the meeting, Viera Rosa said he looked forward to a “methodical and smooth transition to Los Padrinos.”

Board of Supervisors Chair Janice Hahn called it “a tough decision but one we must live with.”

The regulators’ decision to largely shutter the halls came after intense pressure from youth advocate organizations, which accused the board of shirking its legal responsibility and flouting statutory deadlines by consistently giving the county additional time.

In a letter to the board Monday, attorneys with the Youth Law Center and the Peace and Justice Law Center said they would sue if it did not vote to find the halls unsuitable.

Do you know who your L.A. County supervisor is? Do you know how to get her attention? Use Shape Your L.A. to get active in your community.

The vote will not lead to a complete shutdown of Nidorf. The 83 youths housed in its Secure Youth Track Facility, who have been accused of more serious and violent crimes, will remain there. The state board does not have authority over these secure facilities, which were created as something of a replacement for the state Division of Juvenile Justice, which will be closed down at the end of June.

The 18-year-old found dead of an apparent overdose was housed in Nidorf’s secure facility, nicknamed “the Compound.” Two sources told The Times the young man had been dead for hours before officers found him, despite mandatory overnight safety checks. A number of speakers invoked the 18-year-old, Bryan Diaz, by name during the hearing, citing his death as the last in a series of breaking points for L.A. County’s failing juvenile justice system.

At least two other youths who had been transferred to Nidorf’s secure track facility from state custody also overdosed earlier this year, according to court records reviewed by The Times and reports from the Office of the Inspector General. Youths have been able to obtain fentanyl-laced Percocet inside the secure unit, according to the reports.

The state regulatory board’s oversight power could soon be expanded to include authority over secure youth treatment facilities statewide. Penner, head of the board, said Gov. Gavin Newsom has recommended the shift as part of the budget process.

Scott Budnick, a Board of State and Community Corrections member who recused himself from the vote, said changes within the facility need to come fast. He said that he regularly mentored Diaz inside Nidorf and found the conditions abhorrent and the programming nonexistent. Juveniles in custody would wake up at 7 a.m. to play video games and watch TV until the day ended at 9 p.m.

“The kids say to me, ‘Scott, when we do drugs, the day feels like it’s a three-hour day. When we’re staring at that TV all day every day for 70 days in a row, every day feels like 100 hours.’”

He said he sent 10 emails to probation leadership warning that someone was going to die. Caseworkers and probation line staff sent similar pleas. Nothing happened.

“We have to get this right,” Budnick said. “There could be another Bryan Diaz any day now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.